The Nov. 8 midterm elections are expected to be highly competitive. While Republicans are expected to win the House, the Senate race remains contested and may come down to just a few close races, according to FiveThirtyEight.

The outcomes of the midterms also have major implications for policy making. Control of Congress and state governments could determine the the future of pressing issues like abortion rights, election administration, marijuana and crime.

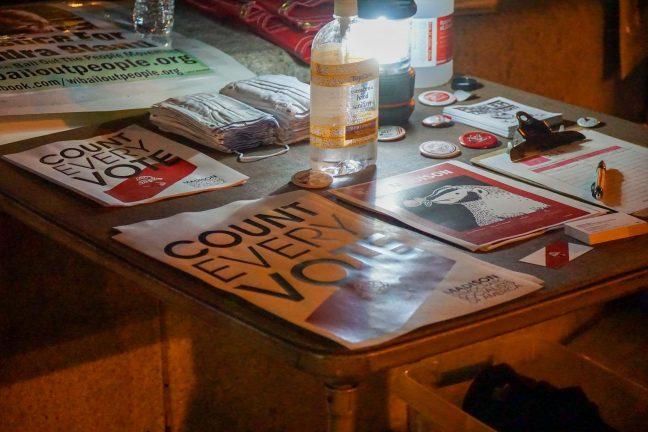

With such high stakes, it is more important than ever that election results are trustworthy. One crucial aspect of a functioning democracy is losers’ consent, which is the ability of the losers in an election to peacefully concede. Without this consent, democratic stability may be challenged by the unsatisfied sector of the electorate.

Political parties branding elections on select issues has negative effects

Unfortunately, a conflicting principle, known as the sore loser effect, also persists. This phenomenon explains that when losers in an election reject the legitimacy of results, violence is more likely to follow. This has deeply concerning implications for the trust in electoral processes and the resilience of democracy.

Some of this distrust may come from confusing or even seemingly counterintuitive aspects of the electoral process. In order to prevent widespread distrust, we have to keep some things in mind about this year’s midterms.

For one, it is almost guaranteed that we will not have complete results on election night. In 2020, Wisconsin’s election results were certified the day after the election, and according to a report from the New York Times, we may see this pattern again.

Largely, this is a result of a law that prohibits Wisconsin election officials from counting mail ballots before 7 a.m. on Election Day.

Nationwide, disjointed election administration laws between states can also draw out ballot counting. For example, Georgia’s election laws may call for a runoff on Dec. 6 if neither Senate candidate earns 50% of the vote. This means it may take weeks to know which party is in control of Congress.

Turnout trends illustrate young voters’ power to influence election outcomes

Further, there is no statewide system for reporting live election results, according to the Wisconsin Elections Commission. Election officials are not allowed to start releasing results until all votes have been processed, which is usually after 8 p.m. on Election Day. Instead, live election coverage comes from the media, which is not certified.

Voters should also not be alarmed if one candidate receives a large block of votes late in the counting process. While in 2020, Donald Trump claimed these “dumps” of votes were evidence of fraud, this phenomenon is actually just a reflection of patterns in voting behavior.

In Wisconsin, for example, Republicans were more likely to vote in person, and these ballots were counted first, producing the false perception of a sizable lead for Trump. Absentee ballots — which tended to favor Democrats — couldn’t be counted early, which exaggerated this effect. When these ballots were counted, however, President Joe Biden pulled ahead.

It may be confusing, but it’s not suspicious. It’s just the logical consequence of current election procedures.

GOP efforts to restrict voting access reflect antidemocratic values

Milwaukee County — the most populous region of Wisconsin — is sending many absentee ballots to a central location rather than counting them at the polling place. This increases the time it takes for absentee ballots to be counted and will likely result in a wave of Democratic votes late in the counting process.

Considering these circumstances, the main thing to remember is elections are secure. Even proven cases of voter fraud lack the magnitude to impact the results of elections.

Election Day can be a rousing event and it may be tempting to follow along with live coverage. But only the final results count, even when it takes time and resources. This diligence is a reassuring reminder of election officials’ effort to facilitate a free and fair election.

Celia Hiorns ([email protected]) is a sophomore studying journalism and political science.