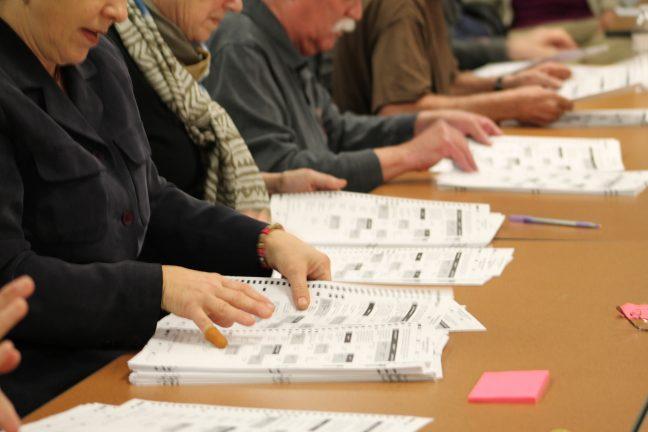

Two referenda are pending approval to appear on Wisconsin’s ballot next year. The referenda would concern constitutional amendments to tighten election administration and are expected to pass in the Republican-controlled legislature.

More specifically, the amendments would prevent private funds from assisting in election administration and adjust language in the Constitution to specifically exclude non-U.S. citizens from voting.

The proposed amendment barring the use of private funds stems from controversy during the 2020 presidential election. During an unconventional year wrought with COVID-19 challenges, state governments required extra funding to support efforts such as administering absentee ballots, hiring poll workers and providing personal protective equipment, according to the Legislative Reference Bureau.

To compensate for these obstacles and ensure voting remained relatively equitable and simple during the pandemic, the Wisconsin state government, as well as others across the country, accepted grants from private organizations. Republicans unsuccessfully advocated to invalidate Wisconsin’s election results on the basis of election bribery. Several lawsuits on the issue at both the state and federal level, however, were dismissed.

Urbanizing agricultural land presents housing, environmental opportunities

Since the failure to change funding laws through the courts, conservative legislators have instead turned to amending Wisconsin’s constitution to establish the legal precedent that would prevent these kinds of donations in the future.

The other amendment would change the language of the Constitution to make voting requirements exclusive rather than inclusive. While federal law states that only U.S. citizens can vote, state and municipal legislatures have been left to enact laws on this issue for local elections. Currently, Wisconsin’s constitution leaves room for ambiguity.

“Every United States citizen age 18 or older who is a resident of an election district in this state is a qualified elector of that district,” the law states. The proposed amendment seeks to clarify that “only a United States citizen” counts as a qualified voter.

Republicans hold that the current language invites suffrage for noncitizens in local elections, which they deem unlawful. Meanwhile, serious debates remain over whether noncitizens should be given the right to vote, as they are equally impacted by the actions of elected officials. If the amendment passes, this crucial discussion over suffrage rights would be shut down.

Undoubtedly, these amendments could make momentous changes in the Wisconsin legislature. Given this, the way the questions are ultimately posed to voters makes a difference. If voters are left to decide on a constitutional amendment, it’s important that they are given the context they need to make an informed choice without being misled.

Wisconsin’s passage of Marsy’s Law via ballot referendum, which is currently being reconsidered by the state Supreme Court, represents a recent example of how this has gone wrong.

In April 2020, a constitutional amendment concerning victims’ rights — versions of which are known as “Marsy’s Law” in other states — was approved by the majority of Wisconsin voters. Republicans pushed for the approval of this ballot referendum for the impacts it would have on the criminal justice system. But the question posed to voters didn’t tell the whole story.

“Shall section 9m of article I of the constitution, which gives certain rights to crime victims, be amended to give crime victims additional rights, to require that the rights of crime victims be protected with equal force to the protections afforded the accused while leaving the federal constitutional rights of the accused intact and to allow crime victims to enforce their rights in court?” the referendum said.

Temporary work visas fail to address fundamental immigration issues

The question’s wording draws attention heavily toward giving the victims of crimes rights — a prospect that would be difficult for many people to oppose. Nearly 75% of Wisconsinites agreed, voting in favor of the amendment. Behind the appealing language, however, Marsy’s Law has the potential to limit the rights of people accused of crimes.

For one, the victim’s right amendment challenges the due process rights of defendants. Parts of the law explain that victims of crimes are allowed to attend and speak at all proceedings relating to their rights in a case. This means that before a defendant even makes their plea, the victim of a crime can provide testimony that undermines the presumption of innocence and can impact how juries interpret the rest of the trial.

The law also says that victims have the right to refuse a request for information from the party of the accused. This means that even if a victim has information that could exonerate an accused defendant and uncover the truth, they are allowed to abstain from an interview. This is in direct conflict with the pursuit of justice.

Third, the amendment asserts that victims are entitled to dispose of a case in a timely manner. This could, realistically, threaten a defendant’s right to appeal decisions made in trial and to ensure the government’s power is kept in check. If there is a conflict between the requirements of a fair trial and a timely disposition, defendants may lose critical rights.

Of course, while the victims of crimes deserve safety and resolution, the nuances of the amendment were not properly represented in the referendum posed to voters. The 16 changes that were made were not noted on the ballot, nor were the real implications for the rights of people accused of crimes.

As the Wisconsin legislature moves toward approving the referenda for next year, it is crucial that wording is decided in a neutral manner. Not only should partisan bodies stay out of the entire process, but questions should be subject to high levels of scrutiny to ensure voters are receiving accurate context before deciding whether to amend the state constitution with a simple “yes” or “no” response.

Ballot referenda are intended to engage the public in the lawmaking process. But with corrupted question-writing, this purpose is overshadowed by the blight of partisan politics.

Celia Hiorns ([email protected]) is a sophomore studying journalism and political science.