In fall 2018, the University of Wisconsin-Madison had an enrollment of 44,411 students, making it the largest school in the UW System by more than 10,000 students.

But UW pales in comparison to the University of Central Florida, which is one of the largest universities in the U.S. at more than 66,000 students. That is well over five times the total population of Granby, Connecticut, the town I grew up in. The university occupies 1,893 acres of land and boasts an annual budget of nearly $2 billion.

More than 1,200 miles away in rural Vermont sits Marlboro College, an institution which enrolls just two hundred students, occupies only 360 acres of land, and has an annual operating budget of just $13.5 million.

These two institutions exist in entirely different worlds. They bear very little resemblance to each other, but at some level, they serve the same purpose — to educate.

At UCF, students benefit from the virtues of a city-sized university — a variety of majors, libraries and dorms rivaling the proportions of skyscrapers, a social and extracurricular setting so vast and diverse that is can cater to even the most specific interests and a network of alumni nestled in every industry.

But despite the size of universities like UCF and its accompanying budget, the typical mega-institution is not without its drawbacks.

Crumbling foundations: Declining enrollment numbers loom over under-funded humanities departments

Perhaps the primary benefit of attending a smaller institution is an overall reduction in class size. Over time, it has become evident to researchers and the general public alike that a smaller class often translates to better classroom production.

“Ask a parent if they want their child in a class of 15 or a class of 25,” William J. Mathis, managing director of the Education and Public Interest Center at CU Boulder, said. “The answer is predictable. Intuitively, they know that smaller classes will provide more personalized attention, a better climate and result in more learning.”

Perhaps the first scientific study to establish an inverse relationship between classroom size and academic performance came in 1979, when Gene Glass and Mary Smith concluded in their now infamous study that once class sizes dropped below 15 or so students, learning progressively increased. Of course, this seems to be an intuitive connection, but it is one which must be considered nonetheless.

There is also a wide array of lesser-known benefits to attending a smaller institution. The “publish-or-perish” mentality at large research institutions has consistently placed teaching lower on the list of priorities for most professors. When a professor’s tenure is dependent upon their work spreading within their field, rather than their lessons spreading among the students, the quality of undergraduate instruction naturally suffers.

Additionally, smaller institutions are known for offering more flexibility in curriculum, allowing students to manipulate their schedule in the fashion they’d like without being forced to plow through requirements which bear little to no relevance to their interests.

But the city-sized college is not without its distinct advantages. Though the in-class experience at a large university is often said to lack a sense of personal connection, extracurricular activities tend to provide a very different atmosphere.

Extracurriculars or coursework: which better prepare students for job market?

“A major benefit of a big college is greater access to extracurricular activities and events, including academic and activity clubs, sporting events, Greek life and social engagements,” education writer Neil Kokemuller said.

At a small institution, it may be difficult to find others who are interested in the same niche topics as yourself. UW currently lists more than 1,000 different student organizations. Interested in chickens? Poultry Club’s got your back. What about clothes? The Apparel and Textile Association is waiting.

Large state schools also tend to come at a much lower cost to students than small private institutions. According to US News, the average cost of attendance for a public university or college for the 2019-2020 academic year was just over $11,000 for in-state residents and about $27,000 for out-of-state residents. In comparison, the average private institution rang up to more than $40,000.

The debate over whether a large university really does suffer in academic quality is an ongoing one.

In 1997, Eric Hanushek of the Hoover Institute concluded in a detailed analysis of 277 studies on class performance, that class size reduction was not an effective means of increasing academic achievement. He cited the fact that class sizes have steadily dropped over the past half-century, yet a significant uptake in test scores has not been observed.

His research has since been challenged, as referenced in the 2016 National Education Policy report where his findings were mentioned.

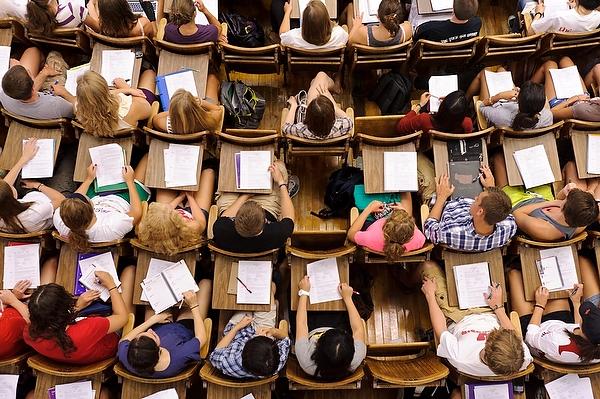

Nevertheless, college education is moving progressively away from the small lecture. UW’s enrollment is its largest since 1986. Across the nation, this trend is continuous. Institutions are growing larger, and lecture halls are beginning to look as though they could host a sizable opera.

The question is, what are we losing in the midst of expansion?

John Grindal ([email protected]) is a freshman studying computer science and neurobiology.