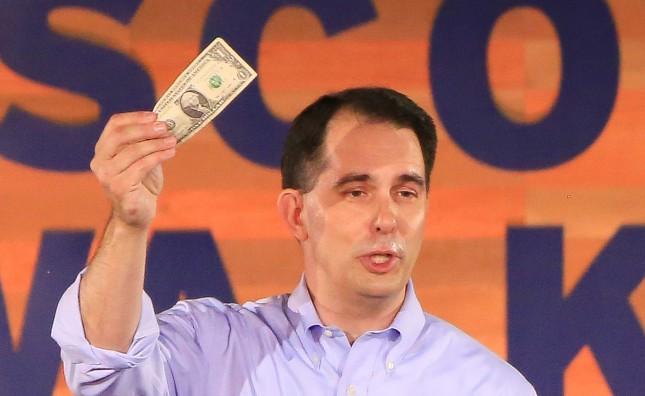

Roughly a decade after the 2008 financial crisis, Wisconsin’s economy has finally recovered. Sort of. The state’s GDP is growing steadily again, the unemployment rate has reached record lows and according to a new report from the Center on Wisconsin Strategy, income has finally returned to pre-recession levels. Sounds great, right? It certainly doesn’t sound so bad for Gov. Scott Walker. After all, the bulk of this recovery has occurred under his tenure.

But looking deeper at the numbers, it’s easy to see what has been called an “economic miracle” may not have been so miraculous after all. Upon comparing Wisconsin’s numbers to that of its neighbors, it’s evident that its recovery has been roughly middle of the pack. From 2008 to present, GDP growth looks unspectacular, as does employment and income, according to graphs generated by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Activity’s online data tool. And though most economists agree that governors have a minimal effect on their state’s economy, the results of a new study from economist Bruce Thompson show that Walker’s policies have cost Wisconsin about 80,000 jobs.

It could be said that 80,000 is an insignificant figure given the state’s 2.9 percent unemployment rate, and that’s fair enough. A slowed recovery is better than no recovery. But the recovery has not been distributed equally. Economists have found current income inequality levels akin to those of the Great Depression, with the top 1 percent of earners making nineteen times what the average worker does. One in five workers earns $12 or less per hour. And, in spite of the job growth, by most estimates, the poverty rate has remained stagnant.

This is where Walker’s record becomes harder to defend. Legislation introduced and passed by his administration have upped requirements needed to be met in order to qualify for poverty assistance programs, making it harder for impoverished and starving Wisconsinites to put food on the table for their families. In order to qualify for food stamps, able-bodied adults must be working or in job training for 30 hours per week (a 10-hour increase), and they may not own a home worth more than $321,000 nor a car worth more than $20,000. Public housing recipients must pass a drug test. Operating under the implicit logic that “poor people are lazy,” the aim of bolstering these requirements is to force Wisconsinites who might “leech off of taxpayer money” to go and find jobs.

And then there’s Wisconsin’s racial inequality. White residents of Wisconsin benefit from one of the nation’s five largest gaps over their black counterparts in income, unemployment rate, poverty rate and child poverty rate. Wisconsin has been named the “worst state for black Americans,” and the “worst state to raise a black child,” along with Milwaukee as one of America’s most segregated cities. White households in Wisconsin earn roughly double what black households do and 41 percent of black and Latino households earn wages placing them at or below the poverty rate.

To Scott Walker’s credit, he did not create these disparities. They have existed for many years, but he certainly wasn’t clamoring to fix them. Instead, he was fighting for the passage of policies disproportionately minorities, such as the voter ID law that deterred roughly 17,000 people from voting in the 2016 election, a disproportionate number of whom are black and/or low-income, and the aforementioned bolstering of welfare requirements.

So, under Walker, is Wisconsin “working and winning?” On one hand, certainly. But on numerous other hands, not quite.

Sammy Fogel (shfogel@wisc.edu) is a freshman majoring in political science and Spanish.