In some ways, Alice Wong did not become an activist by choice.

Being born with a disability, Wong learned early on how to advocate for her accessibility needs. But Wong ended up doing more than just advocate for herself — she founded the Disability Visibility Project to push to change how the media portrays disability.

Wong played a major role in creating the idea of disability justice — a radical framework that centers the voices of queer disabled people of color and works toward collective liberation and joy. Key tenets of disability justice include fostering strong community care and creating a more robust definition of diversity, equity and inclusion.

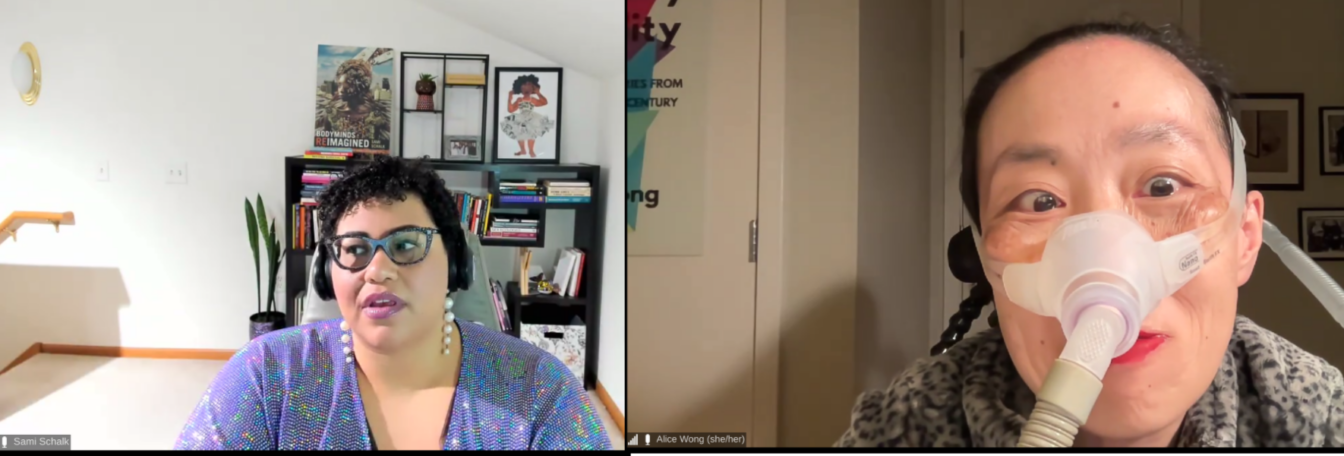

As a lifelong activist and published author of “Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century,” Wong was well-equipped to join Sami Schalk — a University of Wisconsin Gender and Women’s Studies professor and member of the UW Disability Studies Initiative — for a discussion about disability justice as the kickoff of the UW System Women’s and Gender Studies Consortium Conference, which ran April 7 to April 10.

“[Universities] love D.E.I. (diversity, equity and inclusion) … but they forget that if you really want to live those values you have to practice them,” Wong said.

First LGBTQ+ fellowship in nation to launch at UW medical school

Wong and Schalk pointed out that though the disability community — namely disabled people of color — have been hit hardest by the pandemic, they also invented many of the health strategies the mainstream culture used.

“It was my disabled friends who could tell me what the best masks were to get well before anybody was required to wear them,” Schalk said. “Folks were learning from disabled people, even as simple as learning how to use Zoom.”

While ableist and racist oppression has always existed, Wong said the pandemic and recent re-openings have exposed how deep it runs. During the peak of the pandemic, much of the flexibility and accessibility that had been previously denied to the disability community suddenly became widely acceptable because non-disabled people were inconvenienced, Wong explained.

But with society reopening, the opportunities the pandemic offered disabled people are disappearing. For example, UW’s insistence on in-person classes and rigid remote instruction policy has excluded and hurt both immunocompromised instructors and students, Schalk said.

“I see students and myself and colleagues feeling so disempowered in the face of an institution that refuses to remain adaptable outside of that one brief moment where suddenly everyone was so creative and able to think of all the things we can do,” Schalk said.

Drawing on this year’s theme for the Consortium’s Conference, “Centering Resistance: Imaginings of a New Feminist Future,” Wong and Schalk reiterated how valuable the insights of the disabled community have been and will continue to be in the future. To make progress in pandemic and to deal with climate change, the world must continue to listen, the pair said.

For example, Wong said she would not have been able to travel to conferences like the WGSCC pre-pandemic. Holding it fully virtual, as disability justice organizers have been doing for years, reflects how easy it is to be more inclusive and accessible, she said.

Wong also spoke about how a coalition of disabled people of color organized to distribute masks to those affected by the wildfires in California before the pandemic. These two stories highlight the ways in which learning from those in the most marginalized positions of society can pave a better future, Wong said.

“We should really learn from what we’ve experienced and been traumatized by and create a new world,” Wong said. “That’s the way forward.”

Both Schalk and Wong have new books which will be released this fall. Wong’s “Year of the Tiger: An Activist’s Life” will be a memoir reflecting on her own experiences as an Asian American disabled activist, and Schalk’s “Black Disability Politics” will examine how Black activism has and should draw on disability.

Schalk said she hopes her book will contribute to the push for the de-centering of whiteness in disability studies. White people have primarily dominated the field — something which a disability justice approach can rectify, she said.

“We all have the capacity to give joy, to give love,” Wong said. “Mutual aid is so much more than raising money or buying groceries. … A lot of it is just creating space for each other.”