In his 2019-21 executive budget proposal, Gov. Tony Evers recommended a one dollar increase (to $8.25) to the statutory minimum wage by January 1, 2020, followed by a $.75 increase for each of the next three years, bringing the hourly wage to $10.50 by 2023.

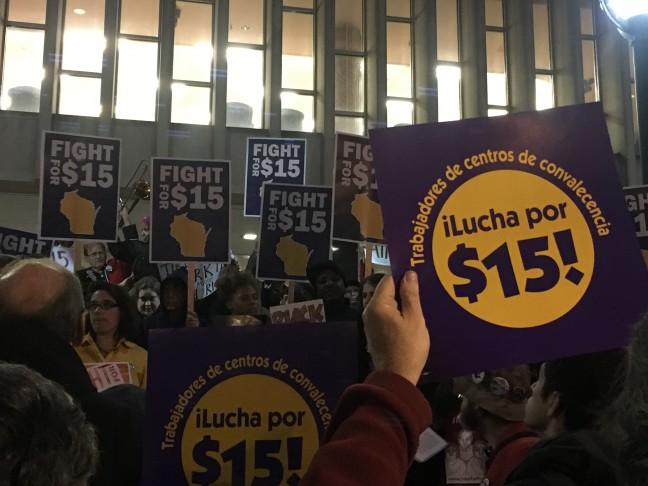

Following these wage hikes, Evers recommended tying the minimum wage to changes in the consumer price index for each year thereafter. Evers has also requested the creation of a task force to study the feasibility of a statewide minimum wage of $15 per hour.

These proposals are almost guaranteed to fail in the GOP-controlled state legislature — but maybe government-controlled wages aren’t as good as they seem.

The movement toward increasing the minimum wage has been sweeping through state and local governments in recent years. For instance, eighteen states started 2018 with increased minimum wages, thanks to previously enacted legislation.

More recently, and a little closer to home, Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker signed into law SB 1, which will increase the minimum wage in Illinois to $9.25 in 2020, followed by steady increases that culminate in $15 by 2025.

But intertwined in the Illinois bill is an acknowledgment of one of the negative effects of minimum wage laws — in this case, the inability of small businesses to afford increased wage costs forced upon them by the government. Illinois created a nonrefundable tax credit for businesses with 50 or fewer full-time employees, which would decrease yearly until 2026.

Supporters of minimum wages explain that it is necessary to protect unskilled or uneducated workers and that the current minimum wage is not a “living wage.” But an increase in the minimum wage would not lift these unskilled workers as much as desired, if at all.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, only 2.3 percent of Wisconsin workers 16 years or older earned an hourly wage at or below $7.25 in 2017. Nearly half of minimum wage workers fall between the ages of 16 and 24. These wages do not include tips, overtime pay or commission, meaning the 2.3 percent includes servers, bartenders and similar workers, who earn unreported tips which bring their wages well above the minimum. Also noteworthy is that the median hourly wage in Wisconsin is $17.81, and the 10th percentile wage is $9.19 — meaning only 10 percent of Wisconsin workers make less than $9.19.

So, the argument follows that these low wage workers would see an increase in earnings and thus see an increase in living standards. But this may not be the case. Rather than seeing an increase in wages, a low-skilled worker is more likely to be let go, making their new hourly wage $0.

This is the effect of a price floor. Less educated and unskilled workers get pushed out of the labor market and are no longer an effective or efficient use of a company’s resources.

In 2017, Wendy’s CEO Bob Wright outlined the company’s three options to offset the rising wage costs. They could cut profit margins, but they’re already at a slim 8 percent. They could raise the prices of their products, but consumers typically respond negatively to price increases, especially on low-cost products. Finally, they could cut hours, fire staff and innovate.

As such, Wendy’s cut 31 hours per week at each of their locations in 2017. McDonald’s plans to implement automated kiosks at all stores by 2020.

Another problem is that for those with increased wages, the cost of living rises. As incomes rise and demand for goods increases, the costs of goods and services also rise. Combine that with rising labor costs, and the price of a dollar menu burger may soon be the “3- or 4-dollar menu.” Thus, increases in wages have no true effect, as costs would also rise, negating the wage increase touted as a benefit to low wage worker.

There are better ways to improve the lives of low wage workers. For one, there are many jobs available that pay well above the minimum wage. Walmart starts at $11 per hour, Costco and Amazon pay $15, the University of Wisconsin and the City of Madison start at a “living wage” of $13.27.

All these employers and many others are constantly hiring new employees. Due to Wisconsin’s extremely low unemployment rate of 3 percent (as of December 2018), there is a growing labor shortage — as this shortage grows, businesses may respond by increasing wages and attracting labor to their companies.

If companies don’t pay decent wages to their employees, or if competing companies raise their wages, they lose good, hard-working employees. The labor market is driven by supply and demand, and competition between firms. The best way for wages to increase is to allow market forces to increase wages — not government mandated wage hikes.

If you don’t like the wages and benefits you’re receiving, there are firms out there which pay better. They’re looking for good employees, and they’re more than willing to pay the premium to get better employees.

Andrew Stein (andrew.stein@wisc.edu) is a senior majoring in political science and economics.