In September our nation took a shrewd second look at the future of Confederate monuments. Dylann Roof hinted at the link between the long-gone Confederacy and domestic terrorism — in Charlottesville, a protester’s murder after the torch-bearing pro-Confederate statue march made that connection clear.

In discussing the future of Confederate monuments in our cities, those who have never bat an eye at a textbook are suddenly decrying the erasure of “history” from our parks and cemeteries. Despite overwhelming support for the removal of these statues, some have become obsessed with slabs of marble and granite — and above all, the “history” they purport to embody.

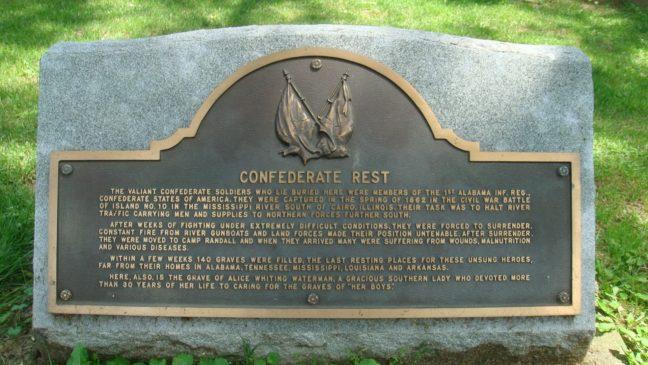

This debate spread across the country like wildfire — in September I wrote an article describing the local conflict in Madison, where two Confederate monuments in Forest Hill cemetery were slated for possible removal. Last week, despite some outlying disapproval, the Madison City Council voted to remove both monuments.

The conclusion to this story is a bittersweet one. It’s sweet because the monuments will no longer exist — bitter because this decision, and the decision to remove statues across the country, still faces vociferous opposition from those who believe their history is being torn down by “politically correct” liberals.

As a history major, renewed national interest in historical events like the Civil War holds exciting potential for me. What we can learn from that era about our shared past — mistakes, triumphs and everything in between — is vital to understanding how those events changed America and how the country has changed since then.

Letter to the Editor: Not all statues with ties to the Confederacy deserve to be removed

We can — and should — discuss the flawed victory of emancipation and the horrors of the Reconstruction South as our country struggled to reunite itself. We can talk about individual battles, their significance and the military strategy honed by the movements of thousands of troops across our nation.

But this isn’t the “history” people are referencing in their defense of Confederate monuments. Rather, these statues and plaques — despite their racist or ill-intentioned origins — are posited as historical tools.

“We can’t and shouldn’t even try to charge or erase or tear down our history,” Gov. Kay Ivey, R-Alabama, said, defending her decision to provide greater protections to historical monuments at a governor’s debate April 11. “We must learn from our history.”

Despite Ivey’s convictions, the assertion statues teach us something we cannot find in textbooks or historical archives is utter ridiculousness. It forgets the scholarship about the Civil War and all its complexities. Most importantly, it misrepresents the literal purpose of statues — to honor and raise up certain figures in history and memory.

And what exactly could a black child learn walking past a Klu Klux Klan-funded statue of Jefferson Davis towering above him except fear?

Those resistant to this transition hold onto the Confederacy in the ways we and the Government have allowed the South to do even after the end of the Civil War. Many commemorate Confederates as brave, tragic examples of the “lost cause” of the nation. They stamp the Confederate flag on their bumpers, fly it in their yards and call themselves “rebels.” They talk about state’s rights in the same breath as Southern pride.

But the Confederacy was not united by a sanitized sense of rebellion and brotherhood. It was not a patriotic failure that deserves praise despite its shortcomings. The Confederacy was a treasonous amalgamation of white men who were terrified at the potential loss of slavery and the control they wielded over others.

The Confederacy at its core fought to preserve the institution of slavery and all it entailed — white supremacy and the ownership of human beings. They fought because they believed the trade and separation of husbands and wives, of mothers and children, was more important than their lives.

And they lost.

The history of the Confederacy cannot be told by romantic statues and plaques commemorating “brave, loyal” men. We have nothing to learn from monuments that misrepresent their subjects, and the intentions behind their creation. Invoking “history” in these instances does a disservice to professors and researchers whose work is worth far more than a singular monument.

Tearing down these statues and placing them in museums puts these shining examples of “history” exactly where they deserve to be: Immortalized with context, and at eye level — never looking down over us.

Julia Brunson ([email protected]) is a sophomore majoring in history.