Here’s an idea for tormented campus progressives looking for a way out of their post-election wilderness: Look back to a Democratic icon of half a century ago who was on the cusp of uniting precisely those angry working-class whites who rallied to President Donald Trump with former Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton’s coalition of minorities and liberals.

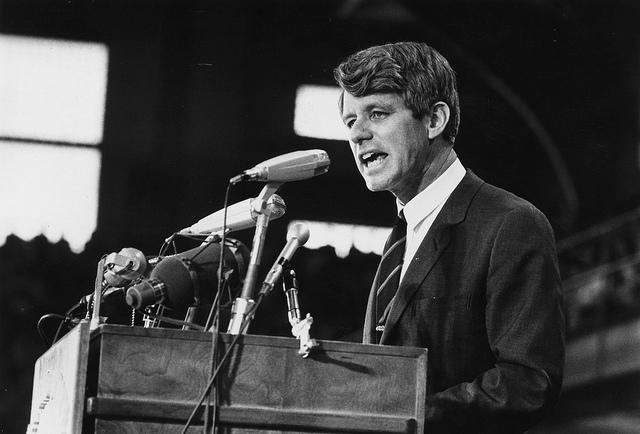

The Robert F. Kennedy who ran for president in 1968 was a racial healer, a tribune for the dispossessed and an uncommon optimist in an age of political distrust. “Each time a man stands up for an ideal,” Bobby reminded us, “he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.” No wonder his audiences swooned. And his words seem even more resonant in this era of Trump.

The first key to Bobby’s broad appeal was that our favorite liberal was nurtured on the rightist orthodoxies of his dynasty-building father and kick-started his career as counsel to the left-baiting Senator Joseph McCarthy. His early conservatism made him an idol to a young Bill O’Reilly and ensured that blue-collar whites stuck with him as he moved leftward. In his first presidential primary, in Indiana, Bobby won the largest counties where the racial backlash candidate George Wallace had done best in 1964 at the same time he scored 85 percent of black votes. The upshot for contemporary Democrats: Stop worrying about ideological purity and find someone with Bobby’s populist passion.

Lesson two for today’s hyper-partisan politics is how, as a senator, Kennedy fashioned bipartisan solutions to nagging problems like rebuilding the Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant, America’s biggest ghetto. Washington would pay for liberal initiatives like training unemployed adults. Tax breaks would lure big business, which drew raves from conservatives. And borrowing an approach from the New Left, local residents would exercise unprecedented self-governance. Half Che Guevara, half Niccolò Machiavelli, Bobby was a shaker-upper dedicated to the art of the possible.

It doesn’t take much imagination to know where Bobby would have stood on President Trump. In college, Kennedy took on the anti-Semitic demagogue Father Leonard Feeney. As attorney general, he stood down the segregation-forever Gov. George Wallace. The only figure who ranked ahead of those two on Bobby’s most-hated list was Roy Cohn, the protégé of Senator McCarthy who, as an old man, was a mentor to the young Donald Trump.

The truest key to Bobby’s political success was his authenticity. Over the course of his 82-day campaign for president, Bobby defied prototypes of pandering politicians. Every speech on crime included a call for justice. He told college kids they could change the world, so why the hell weren’t they? It happened again at a luncheon of Civitans, a men’s service club. As his audience chewed on Salisbury steaks, he turned to his biggest issue — “American children, starving in America” — and asked, “Do you know, there are more rats than people in New York City?” Hearing guffaws, this senator who was kept up nights by images of hungry kids grew grim: “Don’t . . . laugh.” Thomas Congdon, Jr., an editor at The Saturday Evening Post who had started as a Kennedy cynic, was struck by what he witnessed: “He was telling them precisely the opposite of what they wanted to hear.” It was demagoguery in reverse.

What Bobby accomplished in 1968 could be a beacon for 2017. America was as divided then as it is today. Race riots were igniting the cities and overseas tensions were widening the parent-child split. There was no national consensus anymore — and nobody in politics was more determined than RFK to build bridges between the alienated and the mainstream. He’d laid claim to a rare piece of political ground as a pragmatic idealist. Bobby understood that a reformist revolution had to start from the ground up, but he also understood the need for leadership.

“Senator Kennedy is a tough-minded man with a tender heart,” said Senator George McGovern, who stood with Bobby against hunger in America and American involvement in Vietnam. “He is, to borrow Dr. King’s fitting description of the good life, “a creative synthesis of opposites.’”

Larry Tye, the author of Bobby Kennedy: The Making of a Liberal Icon, will be speaking at 6:30 p.m. on Feb. 20 at the Pyle Center.

Larry Tye is an award-winning journalist, a New York Times bestselling author for his biography of Robert Kennedy and currently heads the Health Coverage Foundation. To learn more, visit his website.