University of Wisconsin senior Myranda Breezee arrives at her job at the Mansion Hill Inn every Thursday, Friday and Saturday at 11 p.m.

After she pours out the last rounds at the bar and closes up, Breezee works on homework and stays at the Inn until morning.

When her shift at the Inn ends at 7 a.m. on Fridays, Breezee is off to her second job at the Center for Pre-Law and Pre-Health Advising by 8 a.m. She works there until 2 p.m. — squeezing in a discussion for class at 2:25 p.m. — and later holds office hours for the Center for Academic Excellence until 6 p.m. Then, it is back to the Inn for anоther night shift.

Working three jobs — two on-campus and one off-campus — provides Breezee’s patchwork of income to support her family and her graduate school plans. She would much rather have just one job on campus. But for Breezee, it isn’t a feasible financial option.

“It would be nice if campus paid a little bit more because I do love working on campus,” Breezee said. “It’s convenient, it’s close, the people are great [and] the hours are flexible.”

Breezee isn’t alone in maintaining her employment-school balancing act. Many UW students delicately weigh the benefits of different jobs and it often boils down to a common tradeoff — lower pay at an on-campus job or tougher working conditions and hours at an off-campus job.

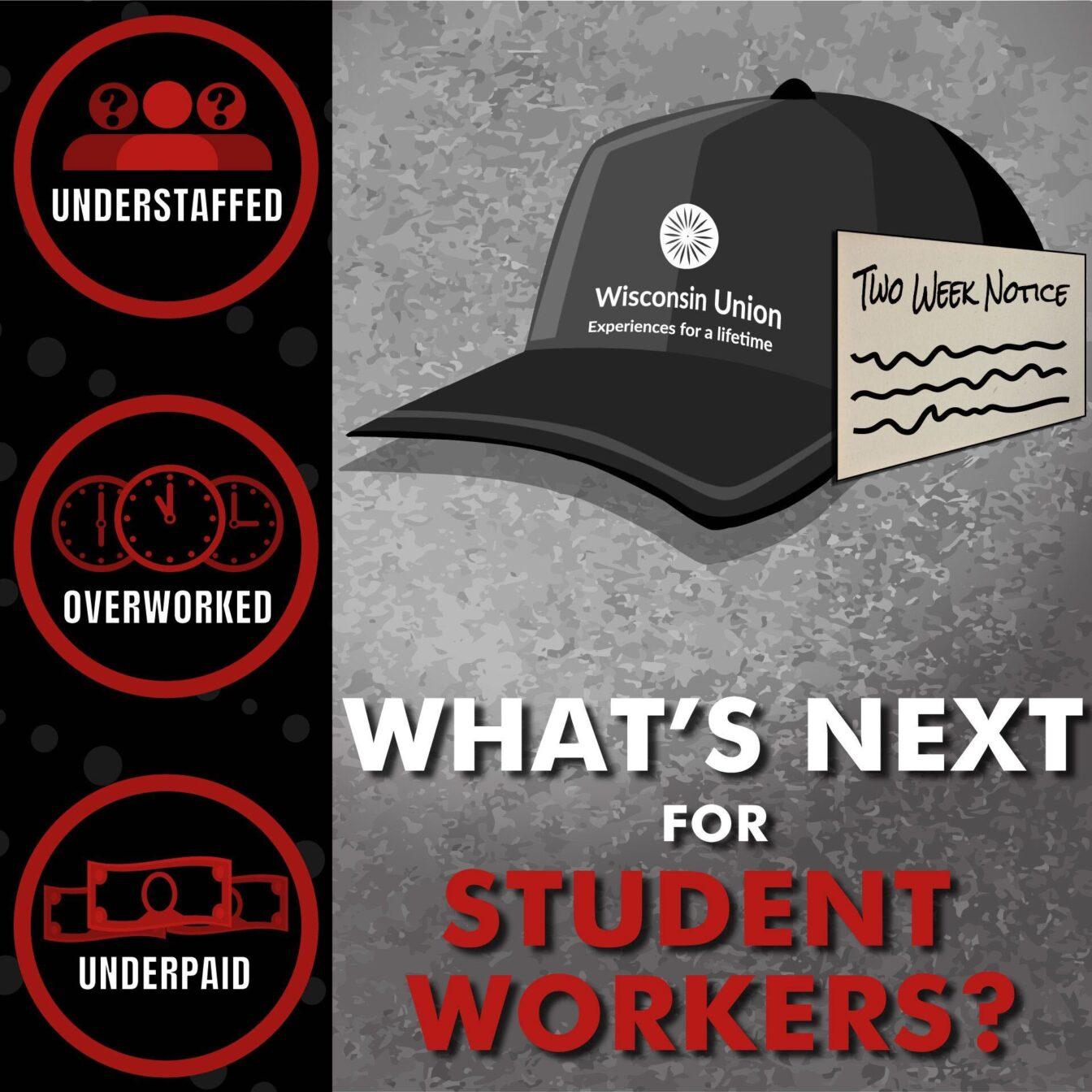

Even as on-campus worker shortages closed down dining halls and left student employers scrambling last year amid the pandemic, students longed for different options to sustain themselves in on-campus jobs that paid enough to make the trade-offs worth it. Several student organizations and some university employers are attempting to meet student workers’ growing demands for better pay, but some students remain left in the dust even as the movement to raise the minimum wage across campus gains traction.

Underpaid and Overworked

Many students rely on jobs, on or off campus, to help pay for tuition, rent or other necessities. This includes Niko Brahmer, who works at Memorial and College Library and holds another job as a bartender downtown.

“The library alone wasn’t really enough to sustain other bills that I pay for with rent and stuff, so I had to pick up another job with it,” Brahmer said.

At campus libraries, the starting pay is $10.50, according to Brahmer, with a 50 cent increase every subsequent semester you work there.

Even for Brahmer, who does not pay for his own tuition, a job on campus does not provide enough money to cover his necessities.

For some students who pay for their own tuition alongside rent and other needs, an on-campus job alone simply does not cut it when it comes time to pay. Oftentimes, off-campus jobs pay more, leading more students to try to get off-campus jobs to make up the difference.

But, this may contribute to some of UW’s recent staffing woes. Last year, some campus entities such as the Wisconsin Union have reduced hours due to understaffing, former Wisconsin Union employee Sophie Mayer said. This summer, Strada, the pizza and pasta restaurant in the Memorial Union, was closed due to staffing shortages.

As more and more of her fellow employees quit their jobs, Mayer’s hours went from 35 a week to 12 a week, eventually leading her to also quit. Mayer felt that the low pay and reduced hours she was receiving in this job were not worth the stress caused by understaffing.

Some Wisconsin Union employees like Mayer attribute lack of motivation to work among students as the cause of staffing issues, which she said could be alleviated with increased pay.

“Everyone’s quitting the food industry,” Mayer said. “Nobody wanted to work, so we didn’t have anyone. I think they expected a lot of people to come in for the school year, but nobody did.”

Abi Miller, who works at the Four Lakes Dining Hall as a shift lead, said the dining hall is also understaffed. Miller makes $12 an hour, working four shifts a week for a total of 16 hours, which is planned relative to a course load of 16 credits.

“It’s a very fun job,” Miller said. “I personally enjoy it. The only issue is we’re severely understaffed, so it becomes very stressful in certain situations where we can’t find enough people to actually run the dining hall.”

To address the issue of understaffing along with other concerns about low wages in the dining halls, University Housing plans to raise their minimum wage to $12 an hour for fall 2022 in addition to raising wages by $2 an hour for the summer, University Housing Director of Marketing & Communications Brendon Dybdahl said.

Some popular campus employers organizations are following suit and making similar pay changes to encourage students to work on campus. The Wisconsin Union is planning to raise their starting wages to $12 an hour for the fall semester, Communications Director Shauna Breneman said.

While raising wages may benefit student employees looking for a raise, it could affect other costs on campus — including student housing costs, Dybdahl said.

“For Housing, there is always a careful balance between employee wages and what we then in turn need to charge our residents for room and board, and we’re very mindful of keeping costs reasonable,” Dybdahl said. “We like to think that what draws students to our jobs in Housing is not just money, but also the flexible hours, convenience and skill development that we’re able to offer.”

Trickle down effects

Whether or not student employers are making plans to raise wages, low-pay and understaffing has already taken its toll across campus.

Understaffing on campus has resulted in many students feeling overworked in their jobs, according to the Student Workers’ Rights Committee’s survey. Several students referenced issues of their time not being respected or being scheduled for too much time, on top of complaints about not receiving enough pay or compensation.

“During the pandemic, what we saw were large draws on emergency relief grants and funding for students who couldn’t afford to work on campus anymore,” former Student Services Finance Committee Chair Maxwell Laubenstein said. “There’s kind of an out-flux of student workers right now to get off-campus jobs because on-campus work is no longer adequately paying or adequately appropriate to the work on hand.”

While 56% of students who responded to the SWRC’s survey reported their job probably or definitely does not impact their ability to perform in school, many students feel they are not well compensated. Out of the 58 students who voiced specific concerns on the survey, 37% mentioned pay or other compensations not being equivalent to the amount of work the job requires.

One position that drew a particularly large number of complaints on the SWRC’s survey: House Fellows. House Fellows, or RAs, are usually juniors or seniors who live in dorms as a resource for students.

An Endless Cycle: Inequities of Wisconsin prison system push advocates to fight for reform

Breaks and compensation were cited as the biggest sources of concern raised by RAs in the survey, noting that some RAs may have to miss parts of school breaks in order to receive their full compensation.

One student, who has been an RA for three years and wished to remain anonymous due to UW policy, said RAs have to agree on who will stay in the dorm over Thanksgiving and spring break, which can lead to some issues if no RAs volunteer. But from their experience, someone has always volunteered — typically an international student who cannot go home for the break. Whoever works over break gets about $25 for 4 hours of work, the RA said.

RAs work under Resident Life Coordinators, or RLCs, who are full-time staff members who run the dorms. The RA said the biggest issue they face with RLCs is lack of communication, especially around the pandemic, and constant switching of RLC positions.

“When COVID first happened, we did not know what in the world was going on or what we should do,” the RA said. “So we would just try to figure out what’s going on, asking our higher ups, but it was like even they didn’t know what was really going on either. So communication needs to be a little bit better.”

Rights and Representation

The Student Services Finance Committee of the Associated Students of Madison voted January 27, 2022 to raise the ASM’s minimum wage to $12 an hour, with 10 votes in favor and one representative abstaining.

“Students have to be able to afford to be represented,” Laubenstein said. “If students can’t afford to work those positions, they can’t afford to have representation on campus.”

Student leaders hope this vote will put pressure on all student employers on campus to raise their minimum wages to livable levels.

One group paving the way for higher wages is the Student Workers’ Rights Committee — a recently founded ASM committee dedicated to advocating for the rights and needs of student workers who administered the campus-wide survey. Though new, the SWRC — created late last semester — aims to alleviate the pressure points for students to make working on campus a viable way to earn money and valuable work experience.

Steven Shi, SWRC’s committee chair, hopes to raise the student minimum wage to $15 over a three-year period to mitigate the effect raising wages would have on student fees and tuition payments.

Shi said that his ideal situation for student jobs is a $15 minimum wage linked to inflation, but he says linking it to inflation may not get support from other committee members.

“There is a consensus that students should be paid fairly, and they should receive a living wage,” Shi said. “I have to admit that I probably am a little bit concerned about raising the tuition and the fees, so I opt for a gradualistic model.”

While Shi acknowledges there are certain state and federal laws the SWRC cannot change that govern wages, he said he will continue to advocate for these changes regardless. Shi also hopes to address what he describes as “manager abuse issues” on campus, noting that even one instance is unacceptable.

“One instant I heard is that [my roommate] had a class to go to, and the managers said, ‘Oh, come on, can’t you just skip that and work here?’” Shi said. “This kind of complete disregard for students’ privacy and students’ time is just outrageous.”

Shi believes managers on campus need to respect students’ school hours and schedules, which he says is a big issue particularly in dining halls.

Shi is particularly concerned for the rights of international students working on campus. To work an off-campus job, international students have to apply for a work permit, which requires a Social Security Number. As a result, many international students take on-campus jobs. The process is very long and involves hourly maximums and exploitation, Shi said.

“A lot of international students work on campus to get an SSN,” Shi said. “Because of that, especially in dining halls, the managers and the whole administration just don’t give a **** about them. Because they know they will stay there because they need something, and they can pay them with a very low wage and still have them stuck there working for them.”

International students also faced pay issues during the 2020-2021 academic year, when UW had a telecommuting policy that prevented undergraduate students working remotely outside the U.S. from being paid. This decision was reversed after student leaders protested the policy.

While the problems within the student employment realm are far from resolved, student leaders believe that the creation of the SWRC will pave the way for better working conditions and better pay.

“SWRC exists to represent students,” Shi said. “We will be the representation for the student workers, and even though this is not as good as having a unionized student workforce, I think this is the right step forward.”