Editor’s note: The Lab Report is a weekly series in The Badger Herald’s print edition where we take a deep dive into the (research) lives of students and professors outside the classroom.

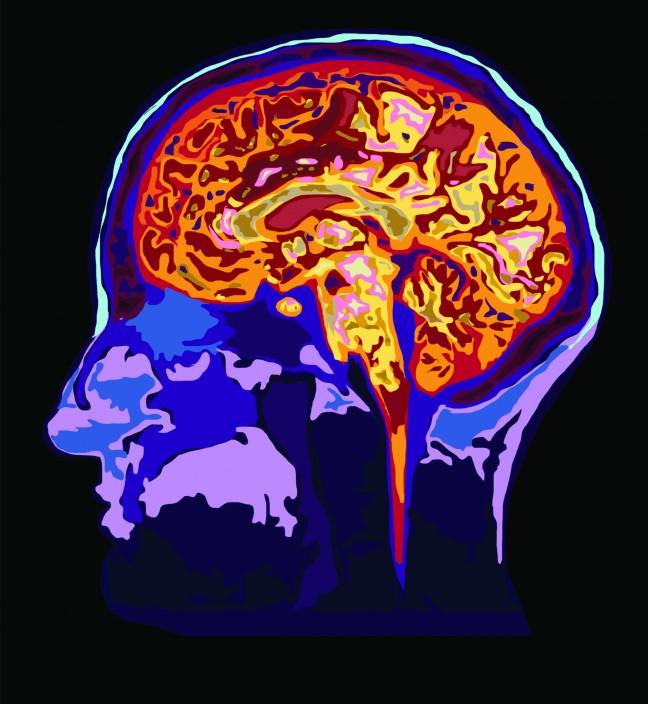

The University of Wisconsin Travers Lab uses their study of motor skills to bridge the gap between the neuroscience of autism spectrum disorder and the daily living skills it impacts.

Principal Investigator Brittany Travers is especially interested in underlying motor differences she observed through learning paradigms, such as typing and folding in individuals with autism.

UPDATED: FDA authorizes booster shots for Moderna, Johnson & Johnson and mixing vaccines

“We think of motor skills as at the nexus between the everyday life tasks and better understanding the neuroscience of autism and other conditions,” Travers said. “We take for granted so often our ability to move our bodies in a way that allows us to react to, and interact with, the world around us.”

The lab studies motor function, cognition and daily living skills in individuals with autism spectrum disorders through an interdisciplinary combination of neuroimaging techniques and quantitative measures.

“We think about what motor differences can tell us about what might be happening in the brain and how motor skills impact our ability to do daily living skill tasks,” Travers said.

Undergraduate researcher Michelle Alder, a senior studying neurobiology on the pre-med track, found her way to Travers’ lab after pursuing a more refined research experience that accommodated her interests in both movement and the brain.

“It’s that intersection between psychology, occupational therapy, and the brain. They don’t leave out any aspect, it’s very holistic,” Alder said. “When you’re looking for results, you’re looking at how is this happening in the brain, how is this presenting physically and how does this relate to helping to improve the daily lives of autistic individuals that may require it?”

Alder’s research experience in Travers’ lab culminated in her recent Hilldale fellowship, providing her with a newfound sense of independence and investment in the lab.

New study finds uncharacterized molecules in vaping aerosols, posing new threats to users

The fellowship provides a unique opportunity to have her own independent project and connect with other students while making a meaningful contribution to the lab’s work, she said. Her project incorporates data collected in the lab with a meta-analysis of existing literature, something she can see the implications of first-hand.

Alder works with two boys with autism in respite care for about a year and a half. She said getting to know the two boys has expanded her understanding of autism on both an interpersonal and neurological level.

“The reading of literature and the results that I’m looking at, I can just see in the kids that I work with how these results could apply to them,” Alder said.

Travers is also excited by the state of their research and how it may translate into meaningful behavioral interventions for individuals with autism.

“We have some work that suggests that intensive balance training may be able to impact the brain and motor ability,” Alder said. “We are excited to think about how intensive behavioral interventions — we call it our biofeedback based video game intervention — and motivating interventions like that may be able to change the entire brain network.”

Travers compared the process of developing a research project to a Venn diagram, with the ideal research project at the intersection of the student’s interests, the literature’s pressing questions and a feasible timeline.

Among suggestions from researchers that motor functions and the ability to move are a result of the evolution of the human brain, the Travers lab focuses a lot on studying the brain stem, an early developing area of the brain lacking neuroimaging perspectives, Travers said.

“It’s opened up doors for us to explore this uncharted territory of the brainstem and better understand all of its functions and how that might lead to motor and behavioral differences,” Travers said.

Alder gained a host of skills thanks to the research process, she said, both in developing her independent project, executing the data collection and assessing scientific literature.

Her mentor played an immense role in guiding her while still giving her a sense of autonomy.

From skills as foundational as learning how to code using an R program to finding and critiquing reliable literature, Alder credits her lab experience as arming her with the tools to be successful.

“This lab is really good at critically analyzing the literature we read, thinking about their choices in their method and how they apply these results to daily lives of autistic individuals,” she said.