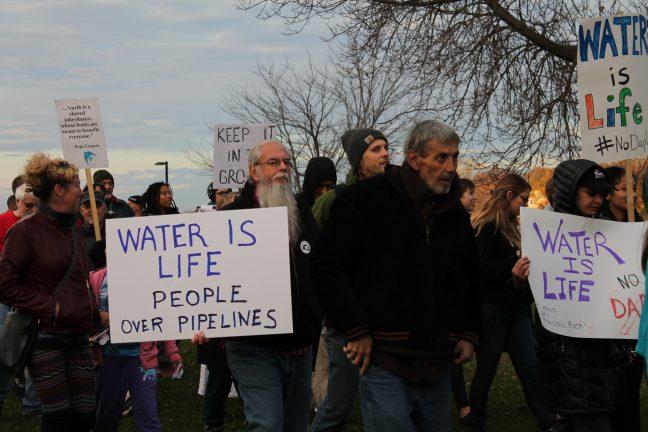

Those fighting the Dakota Access Pipeline are running low on options. While legal challenges may yet prove fruitful for the Standing Rock Sioux, the prospects for their case look dim. Despite the threat to the health and sovereignty of the Standing Rock inhabitants, the final piece of the pipeline will likely be laid soon. As the camp of the Water Protectors is cleared, and construction of the segment crossing under the Missouri River resumes, another chapter in the sad history of Native Americans’ relationship with the U.S. government comes to an anticlimactic close.

Superficially, this appears just another instance of corporate action at the expense of a marginalized minority group. This is not the case. The Standing Rock Sioux are indeed a marginalized minority, but they are first and foremost a recognized political entity, with a formal relationship to the federal government. They are a tribal nation, one that is supposed to enjoy sovereignty over its affairs, people and resources. But as the case of DAPL shows, the status of many supposedly sovereign tribal nations lingers in an uneasy place between partial and minimal autonomy. There are countless treaties between these nations and the federal government, but they seem to exist merely to be broken by those in power.

This is disappointing, but not surprising. I do not think a single international treaty has ever been upheld on honor alone. Clearly, sovereignty does not become real until the nation in question has the means to defend itself and the agreements that it has made with others, a capacity that the indigenous people of this country currently lack. If any indigenous tribal nation is to ever be emancipated from the abuses of the federal government and American corporate interests, it needs to have a military.

The development of effective armed forces is the surest path to true sovereignty. Nonviolent resistance has its own power, but it only works in exceptional cases. More often than we care to admit, it leads to tragedy. Look at Tibet, a sovereign nation that continues to burn under Chinese occupation, even after decades of impassioned and dedicated nonviolent resistance. History shows that there comes a time for every nation to show strength, or fall under subjugation.

The U.S. was no exception. Even after the Treaty of Paris secured for us legal independence, the British continued to violate our sovereignty at will, even going so far as to capture American ships and press their crews into the service of the king. It wasn’t until the American victory in the War of 1812 that our independence was truly decided. It seems inherent that if indigenous tribal groups are to claim sovereignty, they will someday need to back up that claim with military force.

The question remains, however, of how to establish armed forces on resource-poor indigenous reservations. One answer is intertribal cooperation, a shared indigenous military that would spread the burden of maintenance and the promise of protection across several tribal nations. The greatest potential, however, lies in foreign military aid. There are more than a few countries that bear a burning grievance against the United States. These countries ought to leap at a chance to frustrate American policy within our very borders, by providing materiel and military advisors to the tribal nations. With the support of larger nations, the capacity of these tribal nations to defend their sovereignty and treaty rights would be greatly expanded. Through these two measures, I propose that a considerable tribal military could become a reality.

The argument for the development of an indigenous military force may strike some as an incitation to violence. It is not. I am truly arguing for peace, but a more just peace, negotiated under terms of greater equality.

The possibility of bloody reprisal does give me pause. I admit any military mustered by the tribal nations would be dwarfed by the armed forces of the U.S. American soldiers have massacred Sioux people before — I am not so naïve as to suppose we have become more humane since that last happened.

This is a different era, though. Conflict in the wealthy West rarely happens nowadays without attracting the attention of the world — the massacre of politically marginalized people would be an international embarrassment for the U.S. What’s more, I have the feeling indigenous people are no safer unarmed than they would be with a standing military. Our current president’s Jacksonian attitude suggests any fight to preserve the rights of the tribes, whether armed or not, will provoke a heavy-handed response. Under these conditions, it is better to have the protection of an effective military than not.

For the sake of progressive values, reinstate the military draft

As the Sioux and their allies make a peaceful retreat from the banks of the Missouri, we can be grateful that no lives have been lost in this struggle. What else is there to be grateful for, though? The Missouri River, vital to the health of many communities, has been put at serious risk. The American authorities have demonstrated that they are able to trample at will the rights of a supposedly sovereign people. It is time for governmental and corporate interests to take seriously the claim to self-determination put forth by the tribal nations of America. If it takes indigenous military force to achieve this, then so be it.