Across the U.S., in the early hours of morning, Confederate monuments toppled to the ground. In parks, beachfronts and cemeteries, marble and granite were disassembled and carted away. Overnight, something long-accepted and enduring was simply … not.

Discussion over the removal of Confederate statues has placed Americans on opposite sides of an issue that has, recently, only grown more contentious. Claims of heritage and history clash with accusations of white supremacy and racism. Some monuments, like those in Baltimore, were taken down overnight — the future of others remain in limbo.

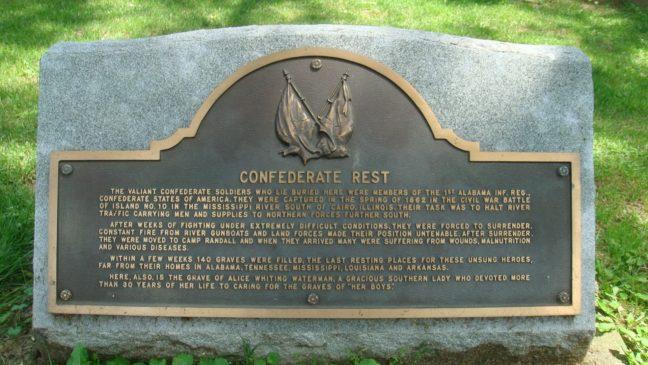

Following the Charlottesville protests, calls for the removal of Confederate monuments reached Madison. After public outcry, officials pledged to remove two local Confederate monuments, including a plaque in Forest Hills cemetery commemorating war prisoners.

A recent letter to the editor, acknowledging that some Confederate monuments should be torn down, stopped short of endorsing the removal of burial plaques. In essence, the author argued, not all statues connected to the Confederacy should be torn down.

The letter posited an interesting, if not philosophical, question: What do we do with plaques commemorating dead soldiers?

The answer can often be unclear. Frequently, we judge monuments by their purpose. A plaque commemorating a battle — or a statue honoring a Founding Father — is rarely considered outside of its historical significance. Often times, the subject is tied into this purpose.

The author makes a fair point in insisting that gravestones should not be taken down indiscriminately. They cite German POW cemeteries as a comparative example, located miles away from the American War Cemetery in Normandy, France. If the French could maintain both these grave sites respectfully, couldn’t we do the same with Confederate burial plaques?

For someone who has visited both these cemeteries, the equation of Confederate and German soldiers is far from nuanced. Burying the enemy’s dead is very different from honoring their mission or legacy. It is not an endorsement of their crimes against humanity. It is the simple respect the French believed all men deserved in death.

The Confederate plaque in Forest Hill was not a product of the same ideology. It was not a monument erected to mark the dead’s location, shortly after the cemetery’s completion. It was not created by those who had known the men, or who buried them.

The plaque was erected in 1982, described as “a slab of propaganda paid for by a racist organization on public property” by Mayor Paul Soglin, who led the charge in getting the monument removed.

Often, when examining Confederate statues’ origins, this jump in time is very common. Though many monuments were erected following the war, historians argue they were actually constructed much later. The majority are found amid a period of brutal lynchings, Jim Crow laws and extreme acts of white supremacy.

As a country, we should be questioning the erection of statues during and following this period. Were we truly building statues to commemorate the lives of soldiers, and the mothers who cried over them? Were we really honoring the dead without glorifying their actions?

In Madison’s case, and in many others, the problem with removal of monuments lies not in the subject of the monument, but in its purpose.

If the Forest Hills plaque was meant to commemorate the lives lost in the war, then doing so more than a hundred years later is redundant. Erecting a plaque and flying Confederate flags over the graves of men recent generations could have never possibly known is confusing at best.

Who — or what — are we honoring here? And why?

One plaque located in Arizona reads “A nation that forgets its past has no future.” Opponents of removal cite this argument frequently: If we remove these statues, then we lose an important part of history, tarnished or not.

But which past are we truly ‘forgetting’? The Confederacy will never be erased from memory. Far from it.

Instead, we are beginning to think critically about how we remember the Confederacy–and, most importantly, how we will let it shape our futures.

Julia Brunson (julia.r.brunson@gmail.com) is a sophomore majoring in history.