A research study has found that three out of five people with Down syndrome will be diagnosed with dementia or Alzheimer’s Disease by the age of 55.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, it has been determined that one out of the hundreds of genes found in chromosome 21 produces amyloid precursor proteins, which are associated with producing amyloid beta proteins.

The chromosome, 21, contains the amyloid precursor protein gene. Amyloid proteins are often cited as being partly responsible for the onset of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, according to National Institute on Aging.

Virtually everyone has a copy of this gene, but how it might affect those who have an extra copy of this chromosome had yet to really be considered. Down syndrome, according to the Alzheimer’s Association, is also called trisomy 21. It is a condition where patients have an extra copy of the chromosome 21.

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin who conducted the study looked at 3,000 individuals ages 21 and older with Down syndrome. The research showed that by age 55, three in five people with Down syndrome will be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or a similar neurodegenerative condition.

This is in line with information from the Alzheimer’s Association, which claims that evidence from autopsies showed that the brains of nearly all adults with Down syndrome revealed signs of dementia by age 40.

According to UW News, the researchers were able to look at data provided by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. The DHS had access to those registered for Medicaid and this allowed researchers to evaluate claims of Alzheimer’s diagnoses in registered Down syndrome patients in Wisconsin.

Eric Rubenstein, lead author and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Wisconsin Waisman Center, described his work as a Special Olympics coach and how it helped him conduct his research.

“I was able to see first-hand the lack of knowledge on the topic,” Rubenstein said. “Being in the research world, it’s [kind of] assumed that people know that dementia and Down syndrome are really linked but in talking to athletes and parents and going to [Special Olympics] events, it seems to be overlooked.”

A common goal among all of the researchers was to raise awareness within the Down syndrome and developmental disability community. The researchers hoped that this research study will get people to start thinking more about the issue, especially families of people with Down syndrome when they are younger, so preventative actions can be taken, Rubenstein said.

Minnesota professor explores correlation between diabetes, dementia

Lauren Bishop, another Waisman Center researcher and professor in the School of Social Work, said the aim of the body of work is “always to help people with disabilities including Down syndrome to live their longest, healthiest, most self-determined lives possible.”

“A big part of that is knowing the health risks and health problems they may encounter as they get older so we can do things to create environments that support their self-determination and independence,” Bishop said.

Rubenstein and Bishop became interested in the topic of Down syndrome linked with dementia when both attended weekly seminars during their fellowships led by leaders in the field of intellectual and developmental disabilities research, they said.

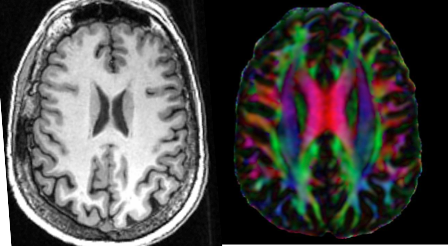

These seminars directed a number of their talks on the link between Down syndrome and dementia but a lot of the studies were based on imaging and small sample sizes.

Both researchers, Rubenstein being in the public health field and Bishop being in social work, saw an opportunity for population-level research to “really understand what is going on at a higher level and not necessarily just small studies,” Rubenstein said.

Sigan Hartley, University of Wisconsin researcher and paper co-author, said this research will ultimately lead them to develop interventions and care for people with Down syndrome that can better provide and service the highly deserving population.

Hartley said she is “excited to get to bring more attention to [the correlation between Down syndrome and increased risk of dementia] because we can secure more funds and some more resources to devote even more attention to [the Down syndrome] population.”