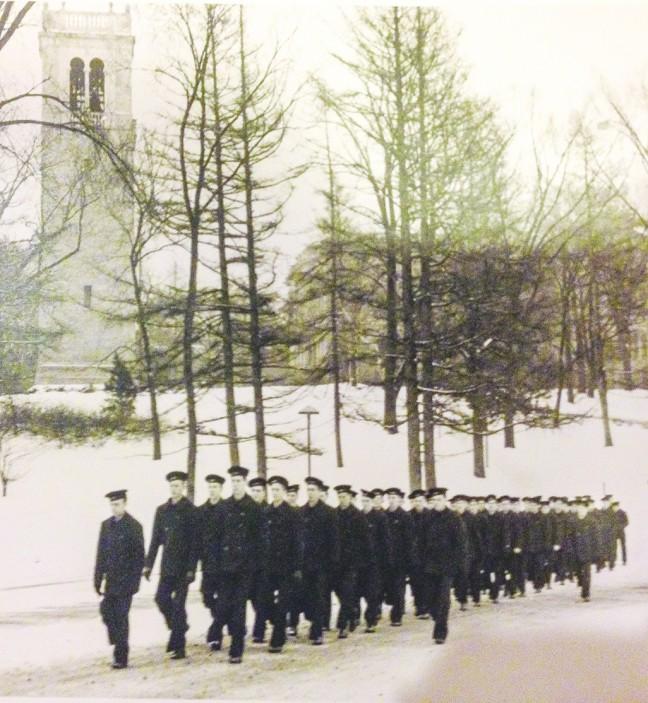

University of Wisconsin’s Lakeshore path and dormitories are known today as the quiet side of campus, but during World War II, the area was known for being home to military servicemen.

Campus life was very different at that time than it is today. Caryl Bremer, a graduate of the UW class of 1947, said she remembers quite clearly the way things had to be when she was in school.

“There weren’t nearly the number of dorms that there are now… so [servicemen] stayed in the dorms and marched to their classes. … There was a rule that Madison students could not live on campus because of the housing shortage,” Bremer said.

Although it was inconvenient for Madison students, no one complained about having to make these sacrifices for servicemen because everyone was in the same boat, Bremer said.

The dynamics of classes were different as well during wartime. Women and servicemen were placed in separate classrooms, and most of the teaching assistants were women because most qualified men were drafted, Bremer said.

Robert Doremus, a former UW English professor and associate dean of Letters and Science, earned his PhD in 1940, but enlisted in the war soon after.

“In 1942, when the draft was breathing down people’s necks I looked around for, as most young men were doing, for some way to be in the armed forces in some other capacity than a private. And the Aviation Cadet Examining Board visited town in May of 1942,” Doremus said in a 1976 interview for the Oral History Project with campus oral historian Laura Smail.

Most young men were anxious to become a part of the war effort, and Doremus was no different. There was a large need for meteorologists in the war, and because of his amount of science classes along with English classes, he graduated with a meteorology degree and enlisted, Doremus said.

The only professors who were men usually had a disability of some sort preventing them from enlisting, Bremer said.

After the war was over in 1945, the housing shortage was still a problem. Madison students still had to commute to classes, and veterans who came back to finish their educations lived in a trailer park next to what is now the Camp Randall Fieldhouse, Bremer said.

“That whole area was all trailers, and the married students lived in those trailers. … They lived in the trailers with their wives, and many of them had children. … It wasn’t real easy but they did it,” Bremer said.

The veterans were dedicated to their studies because after returning from war this was their only chance to get an education, Bremer said.

A big part of the veterans’ education was the help they received from the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, otherwise known as the GI Bill. This bill was passed by Congress to give veterans money in order to pay for school, Bremer said.

However, through the hard work and adversity veterans faced, it was a good time to be alive, Bremer said. They were happy years, and while there was a lack of material items, the different aspects of living in that time were very valuable, she said.