There’s something amusingly obscure about a roomful of prints by Mexican artists mostly done in the first half of the 20th century. It’s a collection that sounds like it belongs in a long, dry conversation with an uncle who heads up an independent tax firm but really had a passion for art history back when he was in school. Next to a Diego Rivera mural – a comparison which the new exhibit in MMoCA directly invokes by calling the prints a “parallel” movement to Mexican muralism – a small, framed lithograph would look insignificant and dwarfed. But ?Tierra y Libertad! has no murals, only prints, and rather than blasting onlookers over the head with colorful, near-narrative art, the collection is interesting in its minute detail and oversized themes.

According to the information provided by the museum, printmaking was embraced by Mexican revolutionaries as a populist, accessible medium. Nearly all the works centered around heavy themes of labor, family and war, though not all were set in Mexico. One, depicting the harrowing scene of hundreds of gaunt bodies jammed into a train car – now made familiar by World War II chapters in history textbooks – was identified as one of the first images of the Holocaust to exist outside of Europe.

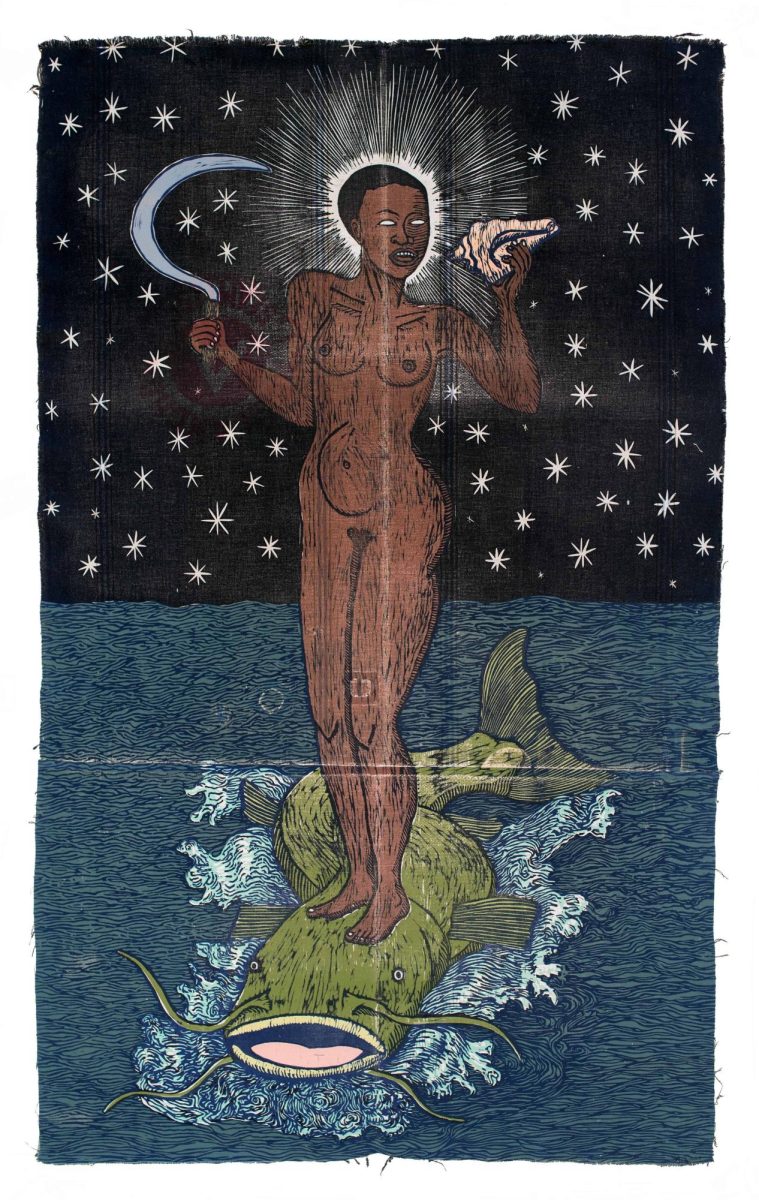

The curators of ?Tierra y Libertad! appear to have had very little interest in the light-hearted or whimsical. This was an intelligent choice; the stark black and whites of woodcuts and etchings cast a high contrast spotlight on their topics; the medium is capable of making even the extremely serious look even more so.

Of the more than 60 prints collected in the exhibit, the most striking was “La Sombra,” a lithograph created in 1939 by Jesus Escobedo. In it, a cloaked man stands. A street lamp is the only light source, and it casts a long shadow (sombra in Spanish) of him and his overcoat into the foreground of the picture. Although the man is obscured, the shadow illuminates a nightmarish scene. There’s a traditional Mexican skull, an emaciated mother and child and a disembodied eye all swirled together into a surreal black and white fantasy. The viewer is left with the impression that these things are either the man’s burden or his memories; he is either awaiting the worst or the worst has already happened.

Not all of the prints are so direct in their message. Another memorable work, titled “Inditos,” or “Indians,” shows several laborers carrying heavy loads. Their features are obscured except for their legs and the things they carry, dehumanizing them to laborer status. A spiky cactus occupies most of the page, but in the background, several mountains loom behind. They’re drawn as simple triangles, and their presence makes the parallel with the exodus from ancient Egypt unavoidable.

On a more meta scale, ?Tierra y Libertad! poses the classic query of artists in turbulent times: Is it enough to simply record what’s going on, or is carving a woodblock of state brutality akin to permission by inaction? Indeed, one print by Leopald M?ndez shows the artist Jose Guadalupe Posada carving a police beating into a zinc engraving – it’s a peek through a window through which there’s a window through which there is war. But the very existence of ?Tierra y Libertad! and the documented importance of the art movement to Mexico answers those questions implicitly: Like history books, art is created by the victors.