Thanks to the discovery of very old observations from “citizen scientists” in Japan and Finland, envisioning the warming of the Earth since the Industrial Revolution just got a little bit easier.

A study published in Nature Scientific Reports Tuesday brought to light nearly 600-year-old records of freezing and thawing patterns of water.

What these records reveal is not particularly surprising — the Earth has experienced increased warming since the Industrial Revolution, John Magnuson, co-author of the study and director emeritus at the University of Wisconsin’s Center for Limnology, said.

“So we didn’t discover something brand new, but we managed to call attention to a dataset based on observation by humans, which, in many ways, are simpler to view and evaluate,” Magnuson said.

In order to attend a workshop on lake ice records around the world at the Center for Limnology’s Trout Lake Station, scientists were required to bring their datasets. The Finnish and Japanese scientists in attendance just happened to come with extremely old and rare records of ice cover change, Magnuson said.

Studies on climate pre-Industrial Revolution are rare. Sapna Sharma, a biologist at York University and co-author of the study, said these records provide context for what the climate was like long before the intense burning of fossil fuels.

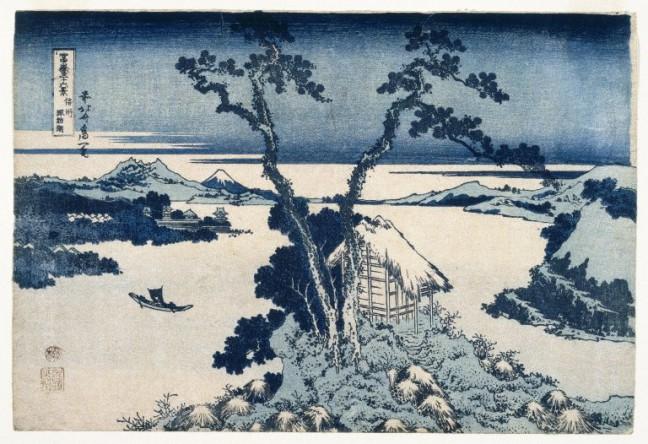

According to the study, priests in Japan began keeping records of ice freeze dates on Lake Suwa in 1442 for religious purposes. A Finnish merchant named Olof Ahlbom began taking annual records of when the ice broke up on the Torne River in 1693. Keeping track of ice seasonability on the Torne was important due to the river’s role in trade, transportation, food and recreation.

Despite being nearly half a world apart, these two bodies of water experienced very similar trends of extreme warmth and changing ice seasonality beginning in the late 18th century. But reviewers were worried these effects were produced by localities, Magnuson said.

In response, the authors decided to enlist experts from both countries who could speak the language, talk to the people and get local information, he said.

“We felt that these things would not have the same patterns if they were a world apart and being determined largely by local factors,” Magnuson said. “Then we quantified the local factors and concluded that they were not important.”

Ice seasonality is sensitive to climatic change, which is why record-keepers have seen later freeze, earlier breakup and shorter ice cover duration since the Industrial Revolution.

The study found the increased prevalence of extreme warm years in both locations have contributed to shorter ice seasonality. From 1443 to 1700, there were only three occasions in which Lake Suwa did not completely freeze over. Suwa has frozen over only five of the past 10 years.

In the case of Finland’s Torne River, extreme warm years were identified by ice breakup dates before early May. This occurred 10 times between 1693 and 1899, but nine times between 2000 and 2013.

The implications of reduced ice cover are still fuzzy. These trends could lead to increased water temperature, algal blooms or changes to fish populations, but concrete consequences remain unclear, Sharma said.

To some, though, ice is a meaningful aspect of their heritage. Magnuson believes the most negative aspect of reduced ice cover in the north is not physical, but emotional.

“The lake is very different if it doesn’t have ice on it, but it’s not different in the sense that it’s badly damaged,” he said. “For people like myself who grew up here and love winter, ice on the lake is part of our sense of place.”

This article was updated to state the Torne River is in Finland.