A report from the Wisconsin Office of Children’s Mental Health revealed suicide rates among young people in Wisconsin have doubled from 2007-15 and continue to rise above the national average.

Nationally, the 2015 rate of suicide among teens aged 15 to 19 was almost 10 per 100,000. Wisconsin’s rate was nearly 12 per 100,000.

Self-harm hospitalizations for those under 18-years-old in Wisconsin have also increased since 2011 — especially among females — as have the number of students receiving community or outpatient mental health services through Medicaid.

Anna Moffit, a parent peer specialist at Wisconsin Family Ties, said the rate has gotten to a “crisis” level.

According to the 117-page report, state health officials also explored potential reasons for these findings and various intervention methods aimed at reducing the upward trend.

Kim Eithun, operation lead at OCMH, said the study demonstrated a need to continue addressing trauma by analyzing adverse childhood experiences.

One way to do this is through the ACE Quiz, which asks 10 yes or no questions about parental abuse, neglect and other signs of a challenging upbringing, Eithun said. If an individual answers “yes” to four or more of the questions, it increases their risk of predisposition to mental or physical illness.

Cheryl Wittke, Safe Communities of Madison and Dane County executive director, contemplated the connection between suicide rates and opioid use in Wisconsin.

According to the report, opioid-related hospitalizations and deaths are increasing as more Wisconsin children are also being removed from their homes due to parental drug abuse — this could constitute at least two adverse childhood experiences.

The Suicide Prevention Resource Center shows suicide rates among those aged 25 to 64 — the age range of most parents — are also gradually rising.

“People who faced some kind of childhood trauma are really at risk,” Wittke said. “If someone in your family has died from suicide, then you’re about six times more likely to die from suicide yourself. It emanates across generations.”

As for college-aged individuals, the University of Wisconsin 2015-16 Healthy Minds Study findings revealed 21 percent of students suffered from depression, while 9 percent had suicidal thoughts within the past year. To combat this, the University Health Services Mental Health Department offers free services like counseling, stress management and 24/7 crisis services.

In relation to other parts of the state, Wittke believes Madison’s urbanness correlates with less gun ownership than rural regions, which, Wittke said could improve means reduction.

“If we can reduce access to lethal means, that’s really the most effective way to reduce suicide because it’s so impulsive,” Wittke said.

Implementing this strategy, Safe Communities launched a campaign in 2016 with Essential Shooting Supplies in Deerfield modeled after New Hampshire’s Gun Shop Project. The educational effort involves posters and brochures aimed at raising awareness and teaching retailers how to spot signs of suicide — like distress or lack of gun knowledge — among customers.

But before individuals reach the legal age to purchase a firearm, Wisconsin Family Ties policy director Joanne Juhnke believes treating childhood mental illness involves integrating several different approaches.

“This is a multi-faceted issue,” Juhnke said. “Looking at it from a bird’s eye view, in addition to the kind of services we provide, in addition to kids accessing mental health services they need, we need to prioritize connection and relationship.”

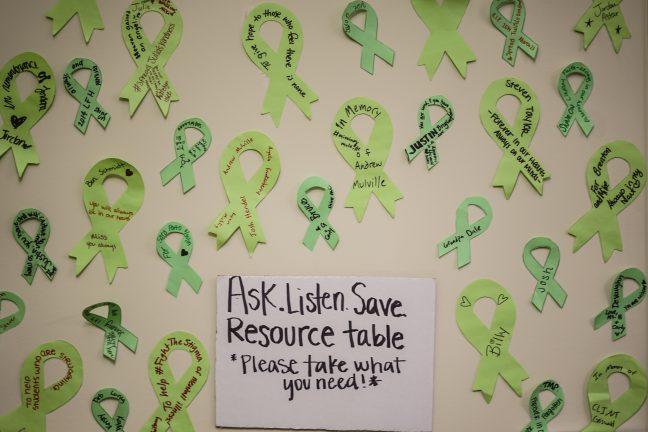

Though the number of Wisconsin K-12 students who received services from community providers integrated into schools tripled from 2013-15, many professionals agreed there is still much more to be done. One Madison high school is severely understaffed, with only two social workers for 2000 students, Moffit said.

Despite this, Moffit believes Madison is off to a good start with programs in place like Building Bridges, a K-5 collaborative effort between social workers and mental health providers to establish services for children struggling with mental health as soon as possible.

In the wake of the OCMH report, Republican and Democratic Wisconsin senators and representatives introduced a bill on Jan. 29 to provide a grant to the Center for Suicide Awareness to take over HOPELINE, a free, statewide 24/7 text-based hotline.

So far, the legislation has garnered support from many mental health organizations, including the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Going forward, Eithun hopes OCMH can continue providing Wisconsin with the information and tools needed to address and treat the state’s rising mental illness rates.

“We know that no one system is going to be able to solve it together,” Eithun said. “Working together and aligning our efforts is what’s best for children and families.”