The University of Wisconsin history department and Harvey Goldberg Center hosted an expert Thursday to discuss how white supremacy was formed and how it has sustained a presence throughout history.

Author Kathleen Belew, an assistant American history professor at the University of Chicago, drew from her book, “Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America,” throughout her lecture. Belew said her book presented a historical account of white power activism — from the movement’s 1975 consolidation to the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing — and how white power activism has resurfaced in the current day.

Belew said she uses the term “white power” because she is a “historian of a military movement that was intent on race war.”

“[White supremacists] carried out activities using strategies to deliberately hide what they were doing, and with deadly and coordinated effectiveness,” Belew said.

Belew said one of the movement’s strategies insisted on being termed “white nationalist” — an obfuscation which advances its violent activity down to the present day.

Belew said the term “white power” is violent enough to fully capture the scope of the movement’s goal, and is thus appropriate.

The white power movement in the United States largely formed after the loss of the Vietnam War because of widespread distrust in public institutions and economic turmoil, Belew said. This caused many to lose faith in the state which they trusted would care for them, and to worry about what American identity would come to mean.

The movement united a wide variety of groups and activists who were affected by these cultural and political shifts, Belew said. Alliances were soon cemented between Klansmen, neo- Nazis and white supremacists with commonly held beliefs.

“These activists organized as a paramilitary army that adopted masculine cultural forms and strict gender roles,” Belew said.

Movement leaders actually declared war on the federal government in 1983, Belew said, and were always looking for new members.

Belew noted that although some of their beliefs align with that era of conservatism, the two should not be connected.

“So how was white power activism so misunderstood by so many people—unconfronted, unresolved, such that the movement could resurface in our present moment? My book is attempting to answer this question,” Belew said.

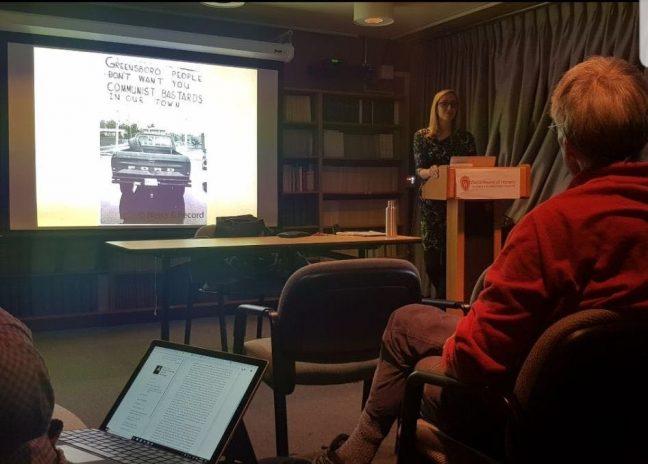

Belew drew parallels between the Charlottesville protests in 2017 and the Greensboro shooting of 1979. On Nov. 3, 1979, KKK Klansmen and neo-Nazi gunmen in Greensboro, N.C., shot and killed five leftist demonstrators.

To prevent future white power violence, the sense of astonishment that often accompanies news coverage of white power activism must be viewed as problematic, Belew said.