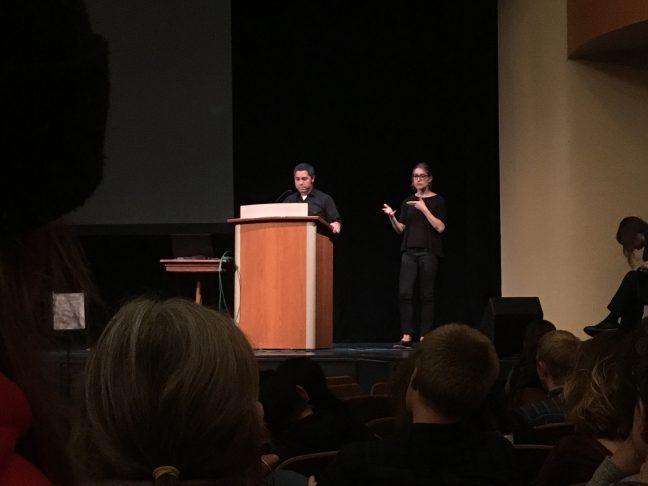

The Wisconsin Union Distinguished Lecture Series hosted archaeologist Jason de León, a University of Mighigan professor, to speak about his work with the Migration Project Thursday.

The Migration Project was founded on the anthropologist research of violent social processes of migration between Latin America and the United States. León travels throughout the Sonoran desert, finding objects such as backpacks, water bottles and clothing, that provide intimate documents on immigrants who are trying to cross the border.

Throughout his work on The Migration Project, León said he is “tired” about hearing of legislation to build a wall between Mexico and the U.S. The wall, he said, would only express an “unnecessary amount of defiance.”

“[The wall is] a way to express your racism in coded racism,” León said.

After spending about five years between the border, León said he has come across many bodies of those who have tried to cross in hopes of a better life.

He explained besides the desert, immigrants struggle with an American legislation called, Prevention Through Deterrence — a policy that pushes immigrants from the cities to the desert.

León said migrant death is not an unintended consequence of border enforcement.

“We have a wall, it is nature itself … We use federal policy to kill people,” León said.

In one study done of the Prevention Through Deterrence policy, it was deemed successful if there was an increase of people’s deaths, León said. While the policy does not necessarily support border control patrols killing immigrants, it does push them to pass through the desert if they want to cross.

After American citizens were being arrested near the border for falsely accused illegal immigration, the U.S. government set up the policy.

“If the deaths of migrants go up, after the policy is put in place, that means it’s being effective,” León said. “Migrant life is constructed as ‘expendable,’ cost of doing enforcement. We think that their lives don’t matter.”

León said it is the desert that proves most deadly in the journey. He said with temperatures upward of 100 degrees, trekking through the desert with cheap shoes, no compass, no map and animals looking to kill migrants, many die on the journey to the border.

León explained individuals may die of dehydration during the summer and drown from a flash flood in the evening. He said the border control will also patrol the valleys of the desert’s mountains, sending the migrants through rough terrain.

“You will be physically exhausted. You will take days, weeks, if not months to recover,” said León.

Not only is it hard for those trying to cross the border, but also for the immigrant’s families. León described the struggles of desert taphonomy and necroviolence, or the mistreatment of corpses.

León said he wants to help as many families through the struggles of necroviolence as he can.

“How do you grieve when there are no bones to mourn over?” León said.

Moving forward, León hopes to spread the need to recognize Latin American immigration problems into the U.S., starting by giving lectures such as the one at the University of Wisconsin. He believes everyone — including students — can make a change by spreading education about immigration policies.