The rise of genetic sequencing, or determining DNA strand sequences, has become faster and cheaper in recent years, leading to an abundance of data that biologists don’t have time to analyze, University of Wisconsin Bioinformatics Resources Core director Derek Pavelec said.

But, scientists have found another way to explore this overflow of data — bioinformatics is a rapidly growing field that merges computer science with biology using genetic data.

UW offers services for researchers who need help analyzing their data using bioinformatics tools at the Bioinformatics Resources Core as well as a very active community of bioinformatics researchers. While many biological science majors don’t receive training in computer science and bioinformatics, associate professor of bacteriology Garret Suen said there is a large demand for students with a command of bioinformatics skills.

“Our ability to generate data far outpaces our ability to analyze that data,” Suen said. “Sequencing is dirt cheap, right? … And so the real challenge is ‘can we develop robust pipelines that can actually predict something?’”

The rise of ChatGPT: ChatGPT makes name for itself in classroom

When Pavelec started working in bioinformatics in the early 2000s, researchers considered sequencing the human genome, or all the genetic material in a person, to be a really big project. Now, researchers are using bioinformatics to answer a wide range of questions.

Bioinformatics tools and programs can look at the expression of certain genes in a single cell and sequence tumors to help develop drug targets. There are now algorithms that can use gene sequence data to reconstruct a person’s face based only on genetic information from a small blood sample, Pavelec said.

One project at UW, known as the MIA Project, is using gene sequencing to find and identify the remains of service members who went missing in WWII. Researchers can take soil samples and determine if it contains human DNA so they can better search for and identify those human remains. Pavelec said this project wouldn’t be possible without advances in bioinformatics.

Wisconsin Energy Institute hosts ‘Black Leaders in Clean Energy and Climate’ panel

“The field has moved significantly in the space of 10 years where none of that really was possible before,” Pavelec said. “That comes down to a marriage between the computational side and scientific side.”

Pavelec was working on his Ph.D. at UW in molecular and cellular pharmacology in the early 2000s when next generation sequencing emerged as the primary source of gene sequence data. Next generation sequencing can sequence DNA faster and cheaper than older gene sequencing methods, Pavelec said.

Next generation sequencing technology was producing more data than existing algorithms could process. To help combat this problem, Pavelec said he combined his knowledge of computers, which was largely a hobby at the time, with his training in genetics in order to analyze the data.

Pavelec now works at the UW Bioinformatics Research Core. The center helps campus researchers analyze data, such as gene sequences or microbiomes, from their experiments. Since the BRC has the tools and computational knowledge to analyze many common types of data, researchers can spend more time interpreting their results, Pavelec said.

“You can just trust that the data was treated appropriately and you’re not going to have some of those errors that you get when you’re just starting out and learning,” Pavelec said.

Unlike Pavelec, Suen started as a computer science major and now uses his computational skills to answer biological questions. After studying the behavior of swarming bacteria in graduate school, he now applies his skills in bioinformatics to dairy cows.

Suen studies the microbiome of dairy cow digestive systems in order to improve milk production. When he’s not in the lab, he also teaches a course on bioinformatics for microbiology graduate students.

Generally, Suen said people who research bioinformatics fall into two categories. There are biologists who want to use bioinformatics to answer their own research questions and researchers who develop the software and algorithms biologists use to analyze data. Suen’s class focuses on the former, and many of his students enter the class with very limited knowledge of computers.

Immersive program teaches Wisconsin landowners about wooded property management

“The running joke in the class is that the only thing I expect you to be able to do is turn on your computer, answer email and maybe post something on Facebook,” Suen said. “So we really start from the ground up.”

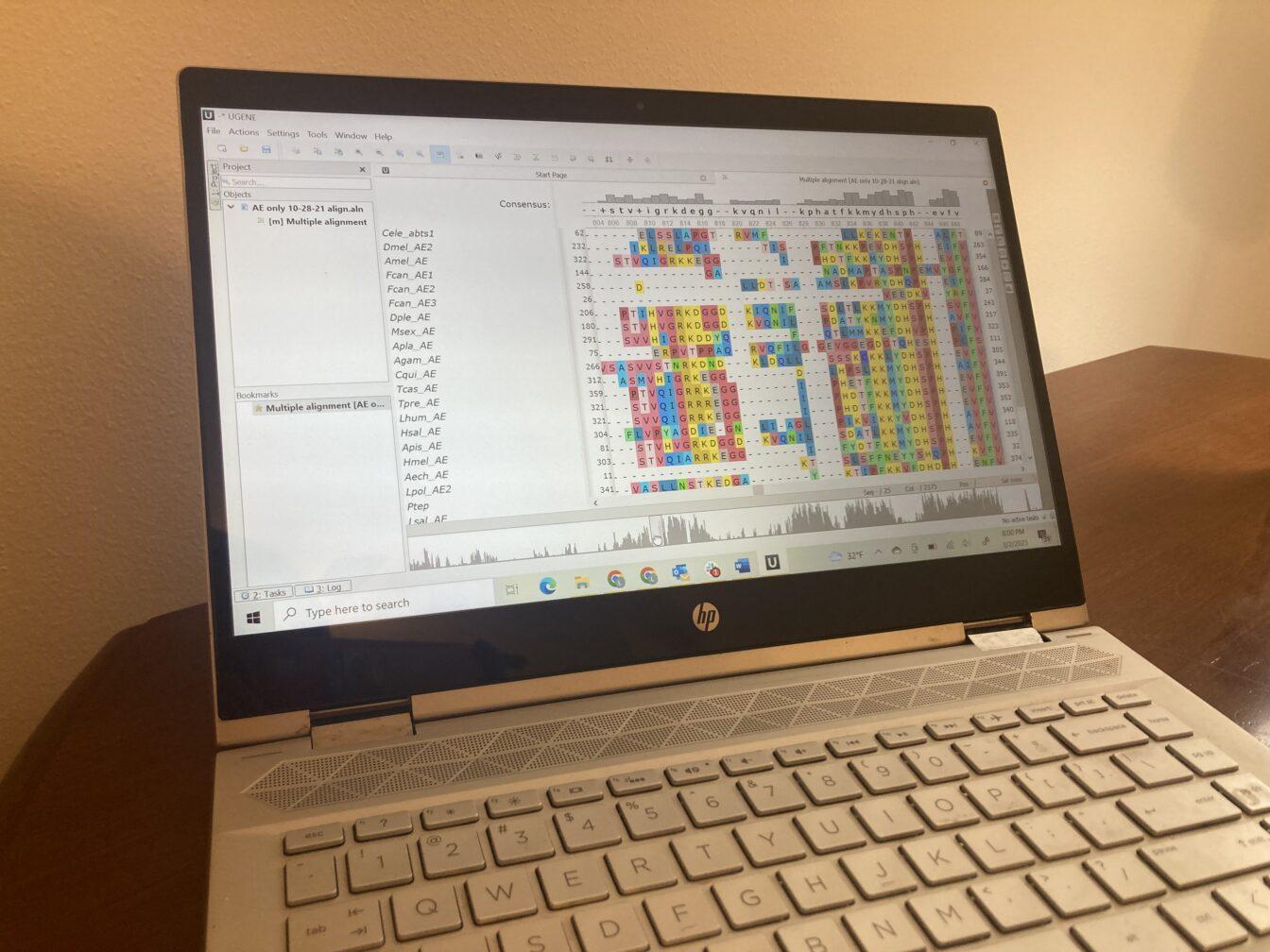

Suen’s class is made up mostly of graduate students, though another professor is designing a scaled-down version for undergraduates. He starts the course by teaching the class how computers work, explains how to download different programs that can analyze different types of information and how to operate those programs using that student’s data. He doesn’t go into the intricate details, but students walk out of the class with a good understanding of how each program works and how to assess the results each program produces.

One common program many biologists use is BLAST, which takes a DNA or protein sequence and finds other similar sequences. The program is helpful for identifying genes that may have a similar function. Suen said his class doesn’t go into the intricate details of dynamic programming that BLAST programs rely on, but students know how to use the program and interpret the validity of the results it produces.

Pavelec said for most biologists it’s important to understand the limitations of different bioinformatics tools and have a solid understanding of how their data is processed. Sometimes researchers find it easier to get help from someone at the BRC than spending time learning to run these programs themselves.

One problem Pavelec often runs into is researchers believe that bioinformatics can generate more answers from a data set than is actually possible. Bioinformatics is a tool, Pavelec said, and researchers still need to spend a lot of time designing effective experiments.

Different computer models also contain errors. Scientists need to understand how these models work and the possible errors that can pop up in order to account for those flaws in the design of their experiments.

“From a bioinformatic perspective, I like having scientists in my core because they understand the biological processes and the gotchas a little more than a computer scientist,” Pavelec said.

Looking ahead, Suen said there are two big problems bioinformaticians seek to solve. First, with vast amounts of data available, researchers are looking for ways to pull useful information from those large datasets efficiently. For example, if doctors ever want to use gene sequencing as a diagnostic tool, they’ll need to be able to attain answers quickly.

Second, with so much data available, there needs to be a way to visualize it. Datasets are getting larger, so traditional figures and plots are no longer going to work.

“So [for] like a doctor or a vet … how do you get that information across in a way that is digestible and consumable in an easy to understand manner?” Suen said. “And I feel like those are probably the biggest challenges that I see as of right now.”