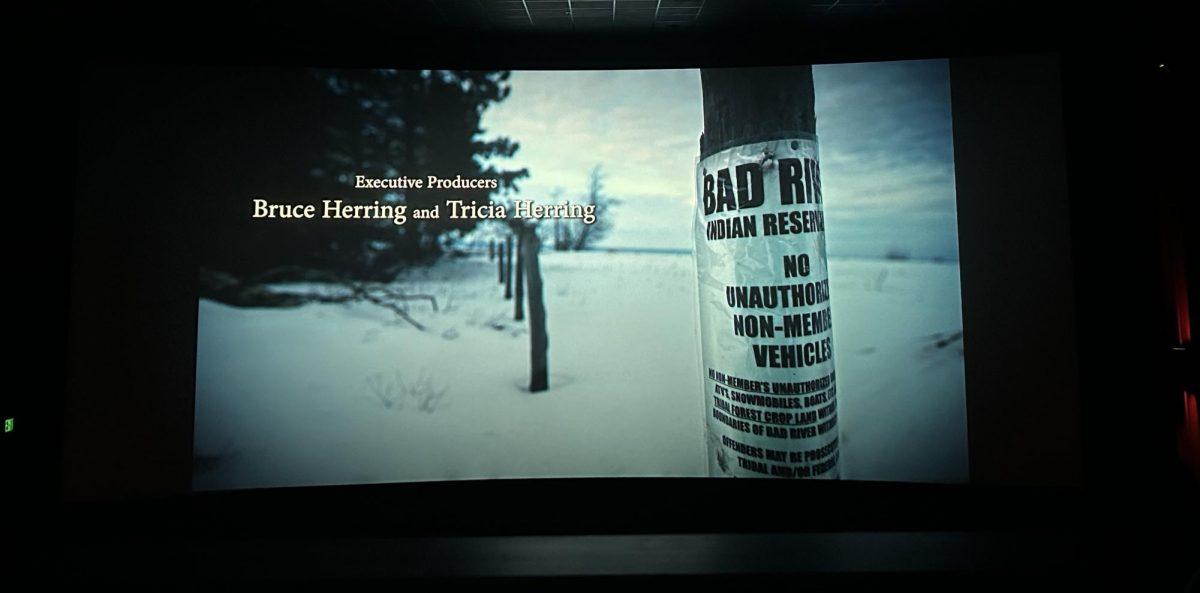

“Rat Film” is a documentary which surprisingly isn’t really about rats at all. Instead, Baltimore-based filmmaker Theo Anthony uses these often-stigmatized creatures as a vehicle to explore social, economic, urban and racial issues in his hometown.

Through his work, Anthony discovers these important social issues and conversations often suffer the same treatment as the tiny mammals: ignorance and disdain. Anthony’s independent, fluid and oftentimes experimental approach to filmmaking results in a product that is a strange combination of the foreign and the familiar. The Badger Herald had the opportunity to sit down with Anthony to discuss his background, artistic style, methodology and yes, rats.

The following interview was edited for style and clarity.

Badger Herald: When did you first get into filmmaking? What’s your background?

Theo Anthony: It started with skating videos and stupid short videos with my friends in high school and college. I taught myself how to edit and shoot. I continued making stuff in college with a close network of friends. That’s still some of my favorite stuff I’ve ever made.

Filmmakers hope to broaden worldview of audience through ‘Walk a Mile in Their Shoes’

After college, I continued to make music videos and got into fashion as well. I had this sort of crisis where I really wasn’t interested in engaging in the world in that way; I actually started doing documentary and moved to the Eastern Congo where I worked as a journalist, working with different organizations over there. After that, I just kept doing documentaries.

BH: Why is documentary such an important part of your authorship? What is it about that medium that draws you in?

TA: Nonfiction, to me, is the most flexible and forgiving of all the forms. Any attempt to constrain it, it’s always one step ahead. For me, there’s this really rough division between fiction and nonfiction and it’s really crude. I think it’s unfair how widespread it is, where nonfiction is stuff that happened and fiction is stuff that didn’t happen. At any certain point in time when you bring a camera into a situation, there’s always going to be a staged element.

Documentary is supposed to be documenting real life and what’s happening, but you have a camera. You have this weird in-between space. Are they themselves or are they performing themselves? Through that, you can explore these fictions that are used to construct nonfiction. For me, it’s a very forgiving form that’s always expanding outwards.

BH: What inspired “Rat Film?” Did you have a very clear idea of what you wanted when you began?

TA: Not at all. I never started out to make a film about rats. I never had this larger idea in mind. I never had any expectations of what this was going to be at any point, and I let it grow very organically. Just very practically speaking, the rat in the trash can shot [came together very organically]. I came home one night. I heard a sound in my trash can, and I took out my camera and starting filming. It was this really haunting image of a creature in a structure, and no matter how hard it tried, it couldn’t get out.

I wasn’t thinking that at the time. It was just a thing I happened to see and happened to record. I starting collecting all these different pieces of information I happened to stumble upon. I read an article about these exterminators in Baltimore. They seemed like really interesting people. I started reading into rat books. I started reading into segregation legislation. All these things were just out there in the world, and it was documentation of my own journey discovering the links between them.

It was crucial to the overall structure of the film — it’s not ever, at any point, trying to be a juicy story of Baltimore or the history of rats. It’s very much a personal story of discovering these other histories that aren’t mine. Acknowledging that gap between my own personal history and the history [I was] exploring.

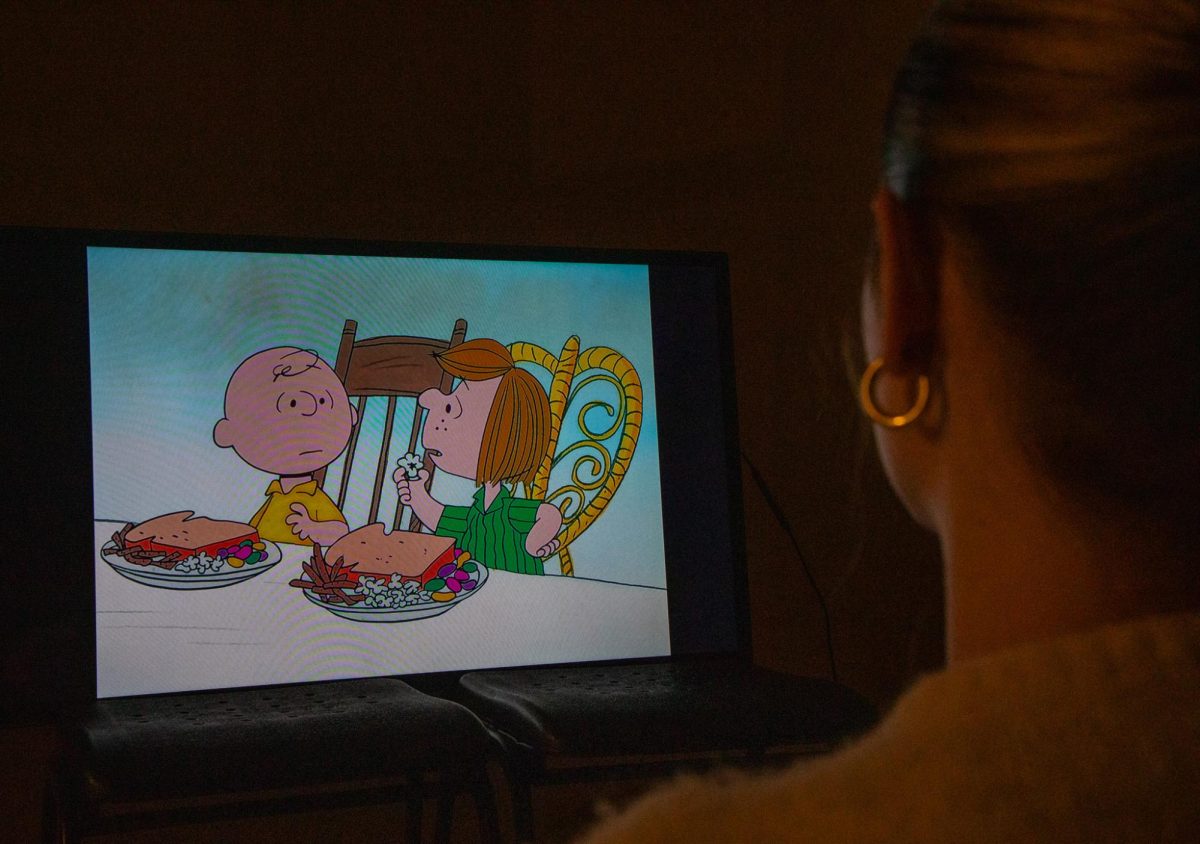

Rewatching “Beauty and the Beast” reveals unnoticed aggression, abuse

BH: How did you shoot this project?

TA: I shoot almost everything myself. 90 percent of it is me, a camera and a subject. I’m sort of used to being a one-man band, in terms of production. On some shoots, I had friends who helped out with sound. From the time I started shooting to the very last shot, it was probably around 8 or 9 months. That was like, on and off. I would have three months of heavy shooting and then take time off. It took about 9 months to edit. It was about a year-and-a-half total.

BH: What was it like working with the musician, Dan Deacon, for the film?

TA: I’m a huge fan of Dan Deacon. He was one of the first shows I went to in Baltimore when I was a teen. It was an amazing opportunity to collaborate with him. Over time we became acquaintances and then friends and then collaborators. Because of that, we’ve become really close friends. I’m so proud of the work Dan did with this. I came to him very early on and said, ‘Can you make music with rats’ basically. We planned this performance involving rats in an enclosure that as they would move about the space it would generate different audio-visual signals. We then captured and used [those signals] in the actual composition of the score.

Dan would watch [the first cut] and then send me a big folder of music inspired by the film. He wouldn’t tell me which sections it was written to, and so I would go and put it in sections I wanted. Oftentimes it would be totally different than [the scenes] he was imagining. I would go and take what he did and change the edit. When I would change the edit, he would change the score. It was like back and forth. That was really amazing. We were just using our different tools to something much bigger than ourselves. It’s changed the way I think about collaboration and how I want to collaborate going forward.

BH: So what is “Rat Film” about?

TA: This film uses rats as an entry point into the conversation about urban planning policies and failures in Baltimore history and what we can learn from how rats have been treated as experimental models. [The rats serve as] models of human experience and what that says about how we actually treat humans. The film never says ‘Oh, rats are humans,’ but there’s a lot of intersecting history. It uses ideas of modeling and who gets to model what environment as a framework for a much larger conversation about filmmaking in general. [The film touches on] what sort of power the filmmaker has over their subject. I always say, ‘It’s about rats but not about rats’.

BH: Congrats on your Gotham Independent Award nomination for Best Documentary. How does that feel?

TA: It feels like I snuck by or something. It’s really awesome. It’s honestly surreal. I can’t say something slick. [“Rat Film”] was such a small thing for so long and it’s so far beyond my wildest dreams of what I was hoping for this or who would see it. To be in a category with Sabaah Folayan and Yance Ford and Frederick Wiseman is wild. I am such a fan of all their work and I’m glad I’ll get to hang out that night.

BH: What’s in the future for you?

TA: We have a couple more weeks of theatrical release for “Rat Film” and I’m just traveling. I’m already in the process of shooting my next film. It’s amazing what has happened with “Rat Film” but I’m happiest when I continue to work and continue the conversation. I think “Rat Film” is great, but I’m ready to continue the conversation in a different output.