Film is the medium for stories about the corrupting power of obsession. Film is a technician’s form, involving everyone working on the same page at the same time to create a watchable product. One needs to look no further than the stories of directors like Werner Herzog or Francis Ford Coppola, who drove themselves to near madness attempting to line innumerable details in place. Like film, these stories shouldn’t be credited just to filmmakers, but the producers, stars and technicians who must work together in perfect, almost impossible harmony. It’s understandable that an industry that’s full of abusive jerks produces hundreds of films about sociopathic men driven to perfection. “Whiplash,” Damien Chazelle’s sophomore feature, fits this theme to a T, telling the story of a teacher’s all-consuming need for perfection and the havoc that it creates.

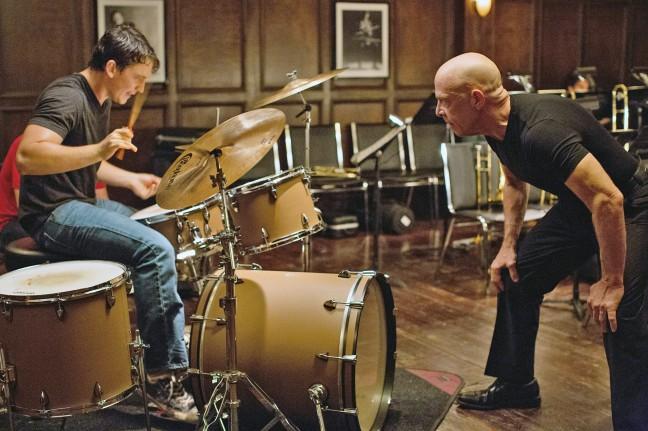

A freshman at the fictional Shaffer Conservatory, Andrew (Miles Teller, “Divergent”) spends all of his time either practicing drums alone or going to the movies with his father. His dream to be one of the all-time great drummers becomes a potential reality when he’s picked up by the school’s top band leader, Terrence Fletcher, (J.K. Simmons, “Men, Women & Children”) to play in his band. Fletcher quickly turns out to be less of a band leader and more of a bully (although he claims you can’t be one without the other). He drives Andrew to cut all ties with his new girlfriend and his family to achieve what he believes Fletcher expects of him. Andrew becomes a victim of his best intentions, and his attempts to fit Fletcher’s impossible needs becomes increasingly violent and disturbed as the film continues.

What appears to be a showcase for its two actors, who turn in the kind of full-throttle performances expected around awards season, turns out to be more of a showcase of Chazelle as a filmmaker. He, his editor (Tom Cross) and his cinematographer (Sharone Meir) dominate the film, making sure the film is able to match its visuals with the emotions and goals of its characters. When Andrew plays or is thinking about jazz, the film cuts to the song’s rhythm. We, the audience, sink into the music and experience its importance to the main character as the film shifts its perspective to mimic it. Chazelle uses these short, close-up shots to give every single movement a sense of importance. He uses the same flair Edgar Wright uses in his films for comedic effect. Another stylistic choice of note: Moments in which Fletcher verbally abuses Andrew keep the focus only on the two of them, which allows Fletcher’s place in his subconscious to become immediately clear to the audience.

In many ways “Whiplash” is not unlike this year’s earlier “Listen Up Philip.” Both stories center around the relationship of a younger artist and an older mentor and how they form an unspoken co-dependence, urging the worst sides in one another. Unlike “Listen Up Philip,” whose stroke of genius wasn’t just showing us Philip’s self-loathing but going in-depth with how that affected those around him, “Whiplash” has trouble outside of its main character. Scenes in which Andrew interacts with his family or girlfriend feel completely perfunctory, driving Andrew to levels of meanness and cruelty that feel inauthentic.

“Whiplash” carries some possible pretensions about capital-M music, frequently name-dropping people like Charlie Parker and Buddy Rich. However, this focus on music and the artistic process isn’t what the film is actually interested in. Rather, it’s the dangers of telling someone the right way to do something. Andrew’s self-loathing and emotional emptying — which become increasingly visceral and violent — and how they cause him to interact with others can be traced back to the standards Fletcher places on him. It’s a credit to Simmons’s performance and Chazelle’s script that we rarely feel that Fletcher is being completely honest. He constantly manipulates and cons Andrew. His lone moments of honesty seem to come from the rare expressions of doubt that he only briefly displays over the course of the film. For Chazelle, hollowness begets hollowness. The film, for the most part, thrives on this ambiguity, never telling the audience whether Fletcher is right or wrong, instead tracking the effects it has and leaving us to draw our own conclusion.

4.5/5

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SvOksqh1Td0