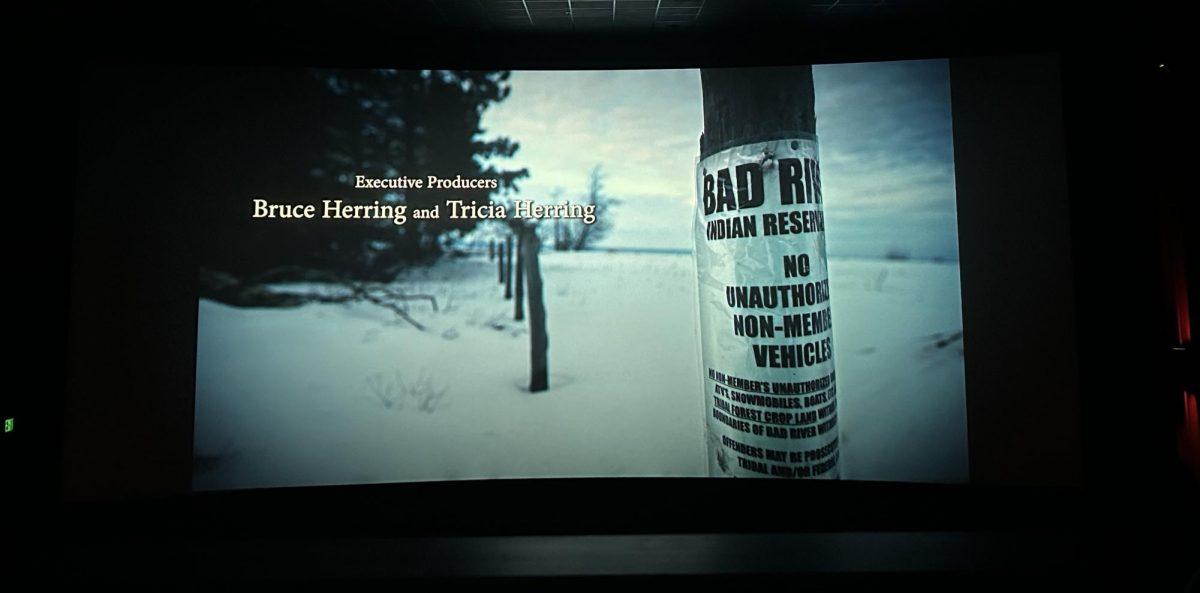

The only significant thing about “The Theory of Everything” is the individual it represents. Otherwise the film, directed by James Marsh (“Man on Wire”), is easily forgettable and insignificant.

It follows the story of renowned English cosmologist Stephen Hawking (Eddie Redmayne, “Les Miserablés”) as a Ph.D. student at Cambridge in 1963, his marriage with Jane Wilde (Felicity Jones, “The Amazing Spiderman 2”) and the motor neuron disease that threatened his life and took away his mobility.

Redmayne does a good job of portraying the early part of Hawking’s life. With a subtly handsome face and a clumsy strut, his early portrait of the intelligent physicist is squirrely, witty and charming. But the truly impressive acting doesn’t emerge till later, as Hawking loses the ability to move. Subsequently, Redmayne loses the ability to use anything other than his facial expression to develop a complex character.

Yet it becomes more and more apparent going forward that Stephen Hawking isn’t the protagonist of this movie. His struggle and apparent conflicts slowly give way to those of Jane, who has been passed the burden of his incredible intellect and controversial ideas. Played with a glowing ease and loveliness, Wilde is the giving tree at the center of the story. She gives up all of herself to support Hawking and his children. With Hawking’s voice becoming more indecipherable, she takes the liberty to translate his ideas, becoming his voice while slowly losing her own.

The film easily translates the admiration that Wilde has for Hawking; however, many of these feelings lose their meaning in the broader cinematic effort to sustain the plot. There is simply not enough time.

The approximate 25-year time frame just doesn’t fit well into a cohesive two-hour film. We get the story, but very little time to reflect on what is actually happening. The events move quickly, and for the sake of expediency, the viewer follows along. What we end up losing is authenticity and it seems like the screenwriter (Anthony McCarten, “Death of a Superhero”) and director took advantage of the biographical nature of the story to shelve the very basic cinematic need for believability.

During the early scenes when Stephen and Jane meet and court and awkwardly dance, I didn’t see love. I saw mediocre chemistry between two talented actors who are trying too hard to be true to their characters, and forgetting that the interaction between them is what’s supposed to make the film touching. At least that’s the goal I pictured after seeing the tear-jerking trailer that brought me to see “The Theory of Everything” in the first place.

The lack of energy put into Hawking and Wilde’s young love makes the later scenes fallible and insincere. We get shards of their actual life together, laughing and kissing and watching their children sit in Hawking’s lap, but these are just cliché little tidbits of lazy screenwriting.

The director is supposed to be illuminating the life of a fantastic man, with clearly intense feelings on life and the universe. Yet we are stuck with this vacuous sitcom-y take on a love story, the only real difference to convention being that the husband is confined to a wheelchair.

Before long, Wilde gets together with her choir leader music teacher Jonathon, played by Charlie Cox (“Legacy”), and Stephen redirects his affections to Elaine Mason (Maxine Peake, “The Falling”), his new nurse. As Jane and Stephen’s marriage has pretty much disintegrated at this point, leaving them just friends, there is no bitterness to these new beginnings. In fact, these latter moments of the film are probably the best, when Stephen finds his voice again through a machine, giving him his iconic computerized American voice. He becomes as charming and funny as he was before the disease took hold, except now he actually seems like his own human, rather than just being a semi-participant in a shaky love story.

I’ll even admit that I shed a tear when Stephen spoke at a conference of sorts and was asked how he finds meaning in life, despite not believing in God. “There should be no boundary to human endeavor … where there is hope, there is life,” Hawking said.

Yet the script, based off of Jane Wilde’s memoir, “Traveling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen,” doesn’t match up with the man it’s representing. His complexity and intelligence is more or less thrown under the rug for the sake of a somewhat boring story about love and devotion. It does nothing new to explain the world of Stephen Hawking, nor does it do much to uncover what marriage between these two very different people was actually like. The details, more or less, fall through the cracks and leave us with very little to walk away with.

As Stephen says to Jane earlier in the film, immediately after his diagnosis, while watching a soap opera on TV, “I’m just trying to work out the mathematical probability of happiness.”

I may not be a physicist, but I spent most of “The Theory of Everything” trying to figure out the same thing.

1.8 out of 5