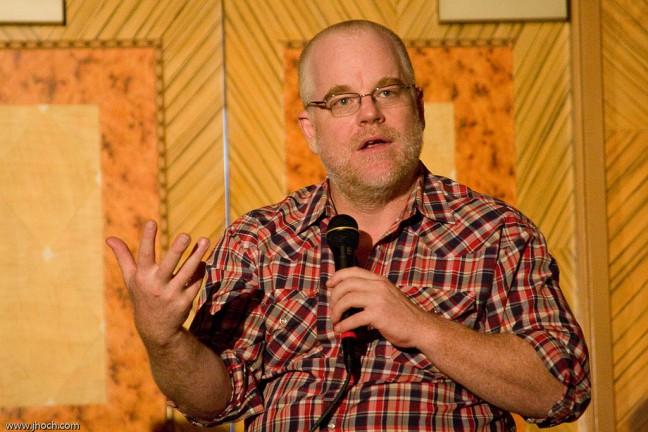

The world lost an incredibly talented and dynamic character actor with the passing of Philip Seymour Hoffman this past weekend. News of his death was shocking, the circumstances around it even more so. Hoffman was cherished in this generation, an actor recognized more for the integrity of his work than the celebrity it created. He was an actor, not a star—an actor so very, very talented that I often forgot he existed.

True to form, I came across Hoffman’s work late into his career—or rather, I came across him late in his career. I was watching “Magnolia,” one of Paul Thomas Anderson’s star-studded films from the ’90s, when something suddenly clicked. I had seen Hoffman in half a dozen roles before this one, but for some reason or another, he was different in this one. I recognized him. His voice, his movements, his features – they were all so familiar to me, so tip-of-the-tongue, but for the life of me I couldn’t match his face to a single name or movie I’d ever seen.

Naturally, I turned to IMDb.

And then I felt like an idiot. A big, gigantic, memory-impaired idiot.

“Twister,” “Boogie Nights,” “The Big Lebowski,” “Almost Famous,” “Cold Mountain,” “Capote,” “Charlie Wilson’s War,” “Doubt,” “Moneyball,” “The Hunger Games: Catching Fire”—the list goes on and on.

He had been in so many Oscar-nominated films that he’d become something of a regular on my screen this past fall. (After wasting two hours of my life this October watching “Playing for Keeps,” I broke up with my Netflix recommendations and promised myself I’d only watch Academy-vetted picks.) And while his looks were by no means chameleon, the characters he played were.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mwpVqRLsVSI

No matter how big or small the role in the film, Hoffman buried himself in his characters. In his Oscar-winning role as the title character in “Capote,” Hoffman sits with Nelle Harper Lee at the premiere party of “To Kill a Mockingbird,” drinking heavily as he contemplates the future of Perry and Dick’s murder trial and weighs his selfishness and career ambitions against the life of a friend and a murderer.

In that moment, all I could think about was the real Capote, his future as an addict and the decisions that led him down that path. After spending so many years intimately tied up in the fragility of human life and monstrous cruelty, how could he not suffer psychological torment? But did I dislike him for it? I had no idea. He was selfish, that much was obvious, and ambitious to a fault, a gross egoist. But he was also scared and overwhelmed; he was simultaneously in love with and terrified by Perry. But what would be worse – letting him die or allowing him to live? Yet another question I couldn’t answer.

That was the genius of Hoffman. Under his guidance, his characters became real, tangible beings – people who were very much faulted and virtuous, selfish and giving all at once. I never remembered them because I already knew them. They were my friends, my family, me. They were the people I passed on the street every day and the ones I ran into at the bar each night. Hoffman’s characters seamlessly wove in and out of the story world, so submerged in the narrative that I often forget there was a real man that existed beneath them. His art wasn’t polluted by his actions in the tabloids or by his political stances on the news. His gift was his anonymity and his talent was his embodiment.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vBoIPm5vEX4

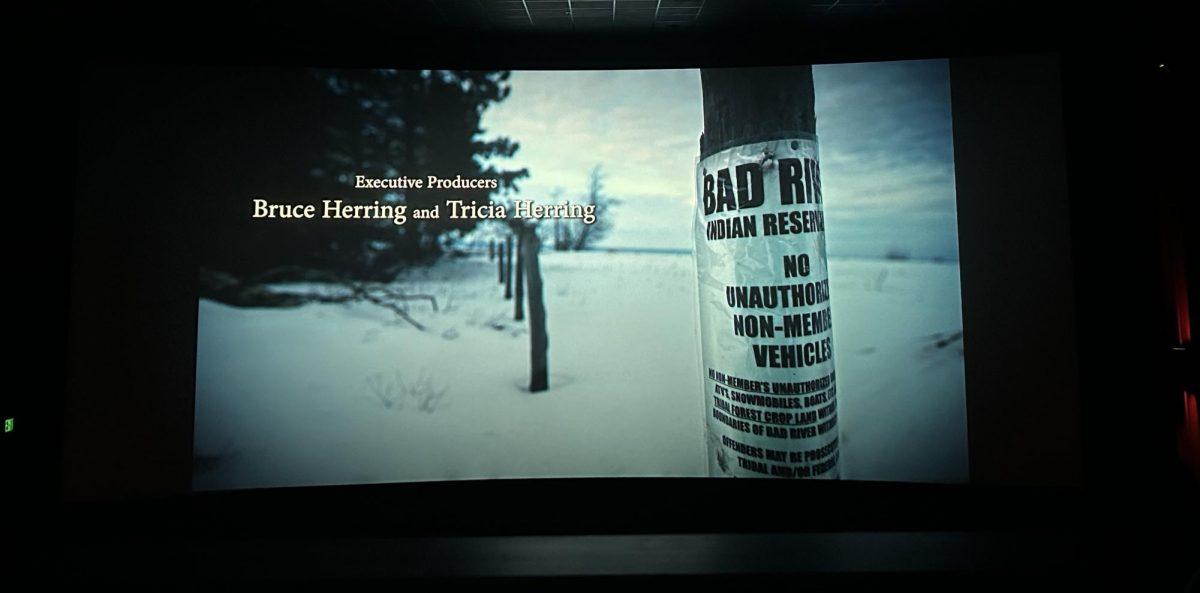

When news broke of Hoffman’s death on Sunday, the world mourned and the Internet erupted. Millions took to Twitter to express their grief and extend their condolences. Anti-drug activists found a fresh platform for engaging in a much needed discussion about Good Samaritan laws and OD first responder practices. Media outlets such as CNN and TMZ began chronicling the actor’s last days, hashing out his “secret struggles” and exposing the “inner demons” that plagued him.

The media frenzy surrounding Hollywood drug fatalities is nothing new – the sadness, the curiosity, the uproar – I get it. And the political power of tragedy to influence policy is something I can also understand. But all the rest is speculation, polluting his work and disrespecting his privacy.

I don’t want to know what Hoffman spent his last days doing. I don’t want to know the demons that plagued him or the third-party opinion of what his road to recovery may or may not have entailed. I don’t want to speculate over his death and I most certainly do not want to “learn” from it.

As a nation, our media and its readers are making a spectacle of a man’s life. And while it is one thing to mourn or create a policy conversation to help circumvent future tragedies, digging into Hoffman’s “sordid past” and “tormented soul” and publicizing that information (however accurate or inaccurate the source may be) is another beast entirely. We should be protecting the personal anonymity in his death that Hoffman so obviously pursued in his life.

Hoffman was an incredibly talented actor whose work consistently boasted profound depth and remarkable breadth. Let’s remember that in these next few days. Let’s celebrate his life as an artist, remembering his genius and reveling in his accomplishments. And as for all the rest, let’s just let it all go.