Heather* had recently broken up with her partner when she began experiencing painful symptoms in her vaginal region, to the point where she couldn’t walk.

She visited a clinic nearby and received a diagnosis of Herpes Simplex Virus 1, commonly known as cold sores of the mouth. It was her first year at the University of Wisconsin.

“It was the worst news of my life. I thought my life was over,” Heather said. “I thought no one would ever want to be near me again.”

Now a senior, Heather has had to share that diagnosis with other partners and navigate ways to have the often uncomfortable conversation about sexual health with them.

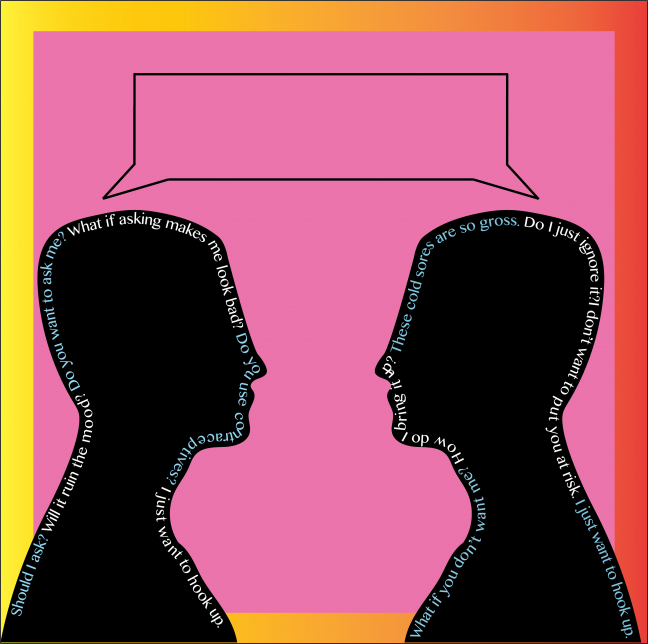

Broaching this topic proves difficult, even for individuals who do not have a sexually transmitted infection. When they are had, the conversations are often uninformed and can further debilitating myths and stereotypes.

“[Partners] have mostly been like, ‘I get it, it’s hard, do you have an outbreak right now?’ And I’m like, ‘no, otherwise I wouldn’t be doing this’ and they’re like, ‘alright then we’re good,’” Heather said. “Then I try to extra explain to them that you can still get it even if I’m not having an outbreak.”

STIs are very common — about 20 million new cases occur every year, according to the Center for Disease Control, with about half of those affecting 15-24 year olds.

Still, living with an STI can be a silent and lonesome diagnosis. Testing positive rarely means the end of the world, but it nearly always means living with the weight of a stigma.

Something nobody wants, but many have

Caroline* felt an instant sinking feeling when she was told she tested positive for chlamydia.

“This isn’t something anybody wants,” Caroline said. “I was scared.”

Initially caught off guard, she took a moment to remind herself STIs are frequent and that once she got the prescription, she’d be OK.

STIs are common on campus, Sex Out Loud program facilitator Madison Neinfeldt said. Chlamydia, molluscum contagiosum (bumps on the skin), HPV and herpes remain the four most common diagnoses.

“Society has this perception that once someone has an STI, it’s a death sentence and their life is over,” Neinfeldt said.

For Heather, negative connotations and alienation muddle conversations surrounding STIs.

An STI, Heather said, is seen as such a “funny” thing to joke about. She witnesses these jokes everywhere from movies to regular conversations. Though rarely intentionally malicious, Heather feels like an outsider whenever she hears them.

“People joke about herpes all the time. It’s in movies. It’s in daily conversations,” Heather said. “It’s such a funny thing to joke about for some reason and then when it actually happens to you, my first thought was ‘wow, I’m a joke now.’ I felt like a leper, I felt untouchable.”

Unlike many other infections, the initial reaction to receiving an STI diagnosis is shame and isolation.

A lonely diagnosis

When she was diagnosed, Heather found solace in online forums with individuals who were going through a similar experience.

The partner who she suspected passed HSV1 to her was also going through the same thing, and she continued to see him.

Because society sees STIs as shameful, people don’t readily talk about them, which can lead to isolation for those who tested positive, University Health Services nurse practitioner Elizabeth Falk-Hanson said.

This alienated Heather and created awkward moments with her partners.

“I don’t really know anyone who has this diagnosis,” Heather said. “I’ve had a lot of shit happen to me and I know people who have had that shit happen to them but this is the first time where I can’t really bond with anyone over this … either they don’t have it or they’re not talking about it.”

When Caroline learned she tested positive for chlamydia, she told her female friends but refrained from telling her male friends for fear they would find her “gross.”

STIs are associated with words like “dirty,” “gross” and “diseased.” However, with few exceptions, most STIs are curable like any other infection.

Sexual health is just like any other type of health, Colton Schellinger, UW senior, said.

Caroline said she wishes more people would take an honest approach. It doesn’t make sense that people aren’t transparent about their sexual health, she said.

“If you want to have a conversation with someone [about STIs], you shouldn’t have to feel afraid about it,” Caroline said.

Widespread lack of sexual education

When it comes to STIs, most people gather their knowledge and form perceptions long before they even enter intimate relationships.

Madhuvanthi Sridhar, a UW senior, grew up in India. Some of her first experiences talking about sexual health were in college.

UW senior and former facilitator for Sex Out Loud Char’lee King said she went to a Catholic high school. She didn’t have much sexual health education until she took it upon herself to learn.

UW sophomore Elizabeth Meek said in an email to The Badger Herald her sexual education was “spotty at best.” Meek’s school’s approach was to promote abstinence as the way to avoid STIs because condoms can fail.

“There was no talk of receptive condoms, dental dams, knowing your status or how to ask for certain tests to be done at the doctor’s office,” Meek said. “Just look up the ‘Mean Girls’ chlamydia scene and you’ll have a pretty good idea of my high school.”

But sometimes, instead of seeking to educate, sex educators use fear-based tactics to dissuade students from partaking in sexual activities. For example, Heather’s health class showed scary pictures of what could happen to individuals if they contract an STI.

Sexual education should be reinforced in college, Heather said.

But because of where the university’s money goes to and where it comes from, they can’t always sponsor sexual health education, Neinfeldt said. That’s where programs like Sex Out Loud comes in.

‘Just like an ear infection’

One common misconception is that preventative measures always protect against STIs, King said.

Like any other aspect of physical health, STI check-ups are important in maintaining sexual health, Falk-Hanson said. Not every infection has symptoms, so individuals should rely more on screenings.

STIs can occur in newly committed relationships, Falk-Hanson said in an email to The Badger Herald. So casual hookups aren’t the only times people should consider getting tested. Many people find themselves with an STI diagnosis despite no symptoms or any reason to suspect risk — particularly for chlamydia and gonorrhea.

Chlamydia and gonnorhea can be detected almost immediately after testing, Falk-Hanson said. STIs including HIV and syphilis, however, can take a little longer to detect. So individuals should have that conversation with a health care provider to understand the risk factors and timeline for different infections.

“Getting checked is a good thing to do,” Schellinger said. “If anyone opens up to you about [being positive], be cool about it.”

At the very least, individuals should be checking on sexual health annually, Falk-Hanson said. But for those who have had multiple partners, she encourages checking in more frequently.

Additionally, the language used when talking about STIs contributes to how people think about them, Neinfeldt said.

“Just like an ear infection, they’re very common,” Neinfeldt said. “That’s why [Sex Out Loud] tries to refer to them as STIs instead of STDs, being that there’s no symptoms a lot of the time.”

Chlamydia, HPV and molluscum contagiosum are all treatable with antibiotics, Neinfeldt said. Getting regular testing and catching STIs early on is the best way to allow them to go away on their own.

There are treatment options for incurable infections — such as herpes — that make outbreaks much more manageable, Neinfeldt said. Knowing the facts and statistics about STIs along with using specific language to talk about them can help debunk myths, Neinfeldt said.

For example, transmitting an STI, though a medically accurate term, can sound scary, Neinfeldt said. “Passing along an STI” is a more comforting phrase.

In Sex Out Loud programs, facilitators encourage participants to refrain from using phrases like “I’m clean.” Instead, Neinfeldt said people should say “I’m negative for an STI.”

“If we say ‘I’m clean,’ what’s the opposite of that? ‘I’m dirty,’” Neinfeldt said. “People who have STIs aren’t inherently dirty.”

Starting the dialogue

The way to clear STI stigmas on interpersonal and institutional levels is through education, King said.

“I sat [my boyfriend] down one day and was like ‘look, I get cold sores, which is technically herpes, and just so you know, I can give it to you sexually … I think you need to know that there’s a risk of that and if that’s not something you want to do, then that’s okay,’” Heather said.

Though reactions have been mainly positive and her partners have been relatively understanding, Heather has had her diagnosis weaponized against her.

With that partner, she didn’t realize she had the potential to spread her STI to him, so they had unprotected sex. He later told her he had contracted it.

“I would never wish that upon anyone. I would never want to give that to anyone, I just felt terrible. But because he really liked me and because I wasn’t as responsive, he used it against me. Saying like ‘you ignored me and didn’t talk to me and now I have this,’” Heather said. “That was really hard to hear because of course, that wasn’t my intention but people can use that and use that against you as if you did that intentionally.”

Conversations like the one Heather had with her boyfriend need to happen outside the bedroom instead of waiting until the heat of the moment, Neinfeldt said. That way, there’s no awkward disruption. Being out of a sexual atmosphere and talking about STIs, especially with a new partner, relieves some of the pressure.

Caroline found out she was positive via a text from a past partner, saying he was positive for chlamydia. At that time, she was seeing someone else. When she found out, she told her partner she had hooked up with someone over the summer and that he should get tested.

“I had to uncomfortably tell [my partner] … I had hooked up with someone a couple months ago, ‘I got this, you should get tested.’ He also had it,” Caroline said. “He wasn’t mad, he was really understanding about the whole thing. I think he was obviously curious because I told him prior to this that I usually use condoms … I had to explain to him that it was one of my ex-boyfriends, but overall he was very understanding about the whole thing.”

People often feel uncomfortable talking about STIs, especially with someone they don’t know that well, Neinfeldt said.

Meek has an “elevator speech” that encompasses her name, pronouns, sexual preferences and status.

“Everyone’s elevator speech can be different but you can toss it out, like: ‘I’m Elizabeth, my pronouns are she, her, hers … I’m not looking for anything serious right now, just looking for a hookup, I do not have any STIs, I was recently tested a month ago … and I’m adamant about using safer sex supplies,’” Meek said. “I don’t necessarily go about it like ‘here’s my elevator speech!’ … it’s more of a spread out thing.”

It’s not a fun thing to talk about, Heather said. That’s why people don’t talk about it and that’s how misinformation gets spread.

Schellinger said he had a partner disclose to him that he had an STI. Though they never had sex, his partner outright told him.

“Communication is the foundation of everything,” King said. “No matter if it’s a long-time relationship or a friend with benefits situation, we can be like ‘hey, I have this thing, and we don’t have to say why this is a thing but I just want to let you know before we continue further … let’s figure out how we want to move forward.’”

Because Schellinger had been previously exposed to friends who had disclosed to him they had STIs, he didn’t have a strong reaction.

Others, like King, ask their partners when they were last tested. If it’s out of the three to six month recommended range, she asks them if they’d be willing to get that updated. But King said she understands talking about being positive for an STI can be embarrassing and uncomfortable.

To alleviate discomfort, Falk-Hanson recommended using “I statements” instead of “you statements.”

“‘I’d feel more comfortable if we were using condoms or if we could talk about when you were last tested,’” Falk-Hanson said. “Otherwise it can be implying […] ‘I don’t trust you’ or think that you have something, so I think reframing it as a ‘me statement’ and trying to say that ‘I’ll enjoy this more if I can feel more comfortable knowing that we’re reducing our risks.’”

That conversation should happen before sexual activities ensue, Neinfeldt said. This has to do with the definition of consent, which is fully knowing what one can expect throughout their sexual encounter.

“To really destigmatize STIs is to really educate people about them,” King said. “We can say ‘oh, they’re not really a big deal’ but unless people believe it, it’s not going to work.”

If you think you have an STI, reach out to UHS for an initial screening.

*Names have been changed to protect the privacy of some sources who have contracted STIs.