The Whitney Museum of American Art’s traveling exhibit “Real/Surreal” has arrived at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art. The exhibit features artwork from the 1920s through the 1940s, with a mixture of works from hyper-realistic to Surrealistic.

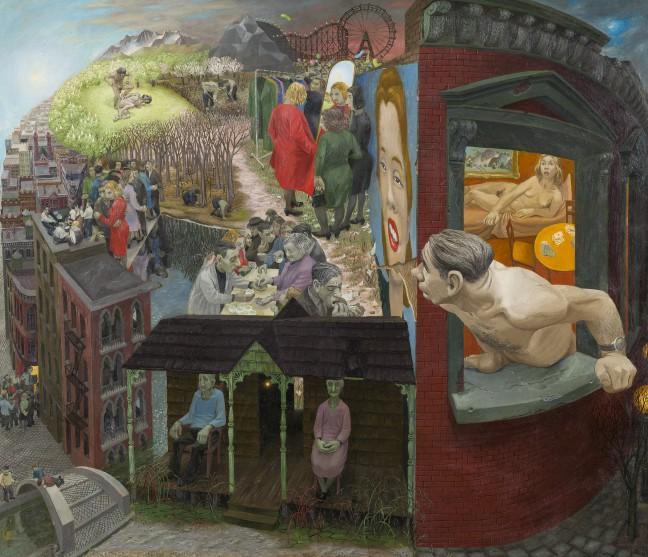

The Surrealist movement in the 1920s intended to synthesize the worlds of unconscious dreaming and conscious perception of reality, and was influenced by Sigmund Freud’s theory of the unconscious mind and interest in dream analysis. Several works in “Real/Surreal” portray the processes of the unconscious mind as a slight distortion to reality, rather than the explicit abstraction or realism found in other works in the exhibit. These works are the most interesting, as they are an experience in entering a modified reality of the artist’s imagination.

The exhibition itself is laid out in an open format, the works mounted on backdrops of deep red and golden yellow. The warm, dark-toned colors give the gallery a cozy feeling — the viewer is aware they are enclosed even though the room is expansive. Often the contrast between works placed beside each other is almost jarring, however even in those places where the works complement one another, the viewer is led through a mixture of images from reality and dreams — and those found somewhere in between.

George Tooker’s “The Subway” is one of the first pieces seen when entering the exhibit. Its central focal point features a group of strangers looking distressed and confused as they pass through the subway. Since the painting has a wide, landscape format but the focal point is in the center, the slight distortion of viewpoint is not perceived immediately, and the figures on the left in coffin-sized booths are not noticed right away. As the viewer spends more time observing the painting, the people in it begin to look more upset, trapped and isolated.

Robert Vickrey’s “The Labyrinth” sports a dark, gloomy hue. At first glance, the painting appears to be just a dark expanse of a twisting maze, with a figure standing in the foreground. Looking again, human faces emerge from the shadows and a distorted reflection of the figure appears — I stopped in my tracks when I spotted the faces morphing out of the walls of the labyrinth, looming at any who pass through the maze. It was unsettling, watching something that initially seemed so plain.

Works which portray scenes in bright colors and are easily decoded, such as “Hudson Street” by George C. Ault, are juxtaposed with works with hidden twists such as “The Labyrinth.” The viewer is left considering which images are realistic and which have “hidden” aspects of Surrealism. The most interesting works are those that display qualities of both.

In other works, the viewer’s conscious mind identifies human-like figures in the landscape featured, which upon closer examination may not actually be bodies of anything living at all. Joe Jones’ 1936 work “American Farm” depicts hills that at first look maybe like a human rib cage or maybe the wrinkles of a walrus. Doris Rosenthal’s “Dead Gods” shares the idea of hills as human-like figures. Works such as this one play with the desire of the human conscious to identify and categorize what they see around them.

At other times, human faces are clearly pictured but are deliberately distorted, such as in “Lily and the Sparrows” by Philip Evergood. The subject’s face and wrinkled hands make her look undeniably creepy and contrast with the scene of an innocent child feeding the sparrows at her window. Lily’s elated, almost rapturous expression contrasts with her creepy depiction, resulting in a bizarre work that made me actually laugh.

“Real/Surreal,” which runs until April 27, features an excellent combination of realistic and Surrealistic works which combine to create the experience of passing through a world that is not quite asleep and not yet awake.