In case you missed it, sexism is still very much a problem in Hollywood. It’s a deeply-rooted, structural form of sexism, but sexism nonetheless. This year’s “Celluloid Ceiling” report from the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University — an annual report that measures employment numbers in the top 250 highest-grossing films of the previous year — reveals that, of the 3,000 employees surveyed, only 16 percent were women. In 1998, 19 percent of employees working in Hollywood were women. The film industry, it seems, is moving backwards. For an industry that prides itself on honoring minorities and celebrating left-leaning politics, this seems like hypocrisy.

The numbers are even worse for female characters in film. In 2013, women made up only 15 percent of film protagonists, according to another study by the Center of the Study of Women in Television and Film. They made up 30 percent of all speaking characters. Female characters were more likely to be young, more likely to have an identifiable marital status, less likely to have identifiable goals and less likely “to be portrayed as leaders of any kind.” Like the numbers on female employment in Hollywood, there seems to be little positive progression for female characters. After all, in 2002, 16 percent of film protagonists were women. Hollywood, you suck.

Yet 2013 seemed like a good year for women in film. Films like “Gravity” featured a female protagonist fighting for her life as she orbits the Earth. “The Hunger Games: Catching Fire” also features a strong, female protagonist. “Frozen” is perhaps the first Disney film to suggest that a woman doesn’t need a man in her life. As co-chairman of Sony Pictures Entertainment Amy Pascal points out in a recent New York Times column, “Between ‘Gravity,’ ‘Hunger Games,’ ‘Frozen,’ ‘The Heat’ and others, that’s $4 billion.” She stresses this as “a gigantic change.”

But this is troubling logic. While 2013 might have appeared to be a good year for women, it’s impossible to argue with the numbers listed above. Saying sexism in Hollywood is ending because of a few successful, female-driven films is like saying, “We have a black president now — guess racism’s ending.” It’s a superficial interpretation of contemporary industry affairs, and it ignores the deep-seated problem at hand.

“Gravity,” despite its brave lead female protagonist — played with strong conviction by Sandra Bullock — is still somewhat problematic. Bullock’s character is prone to fits of anxiety. At times the only solution to her nervousness is the calm, soothing voice of her co-star George Clooney, the comparatively debonair male character who stands in complete opposition to Bullock’s neurotic character. When she comes close to death, the memory of Clooney inspires her to fight for her life. In a film heralded for its “strong female protagonist,” why does this character need to rely so heavily on a man?

As film critic Mike D’Angelo recently observed in the A.V. Club, the phrase “strong female characters” is frequently used, while the converse is rarely discussed. He argues that we need more “weak male characters” in film and notes that in Hollywood’s Golden Age, major male stars were generally confident enough to make themselves look vulnerable (e.g. Henry Fonda in “The Lady Eve”). A film like “Gravity” can have a vulnerable female protagonist — that’s fine. When she’s relying on the strength of her male co-protagonist, though, her female independence is negated. In a film with both male and female protagonists, the balance of power should constantly be shifting. Clooney should also be exhibiting moments of weakness, but those never come.

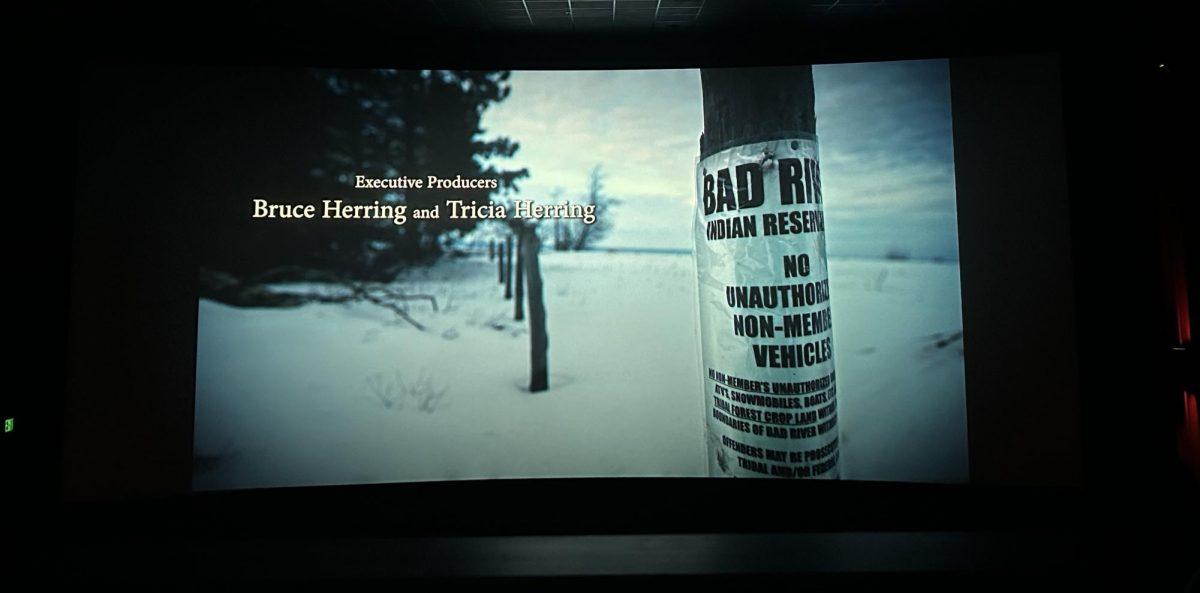

In 2003, Quentin Tarantino’s “Kill Bill” created a cultural firestorm with its dazzling blend of witty dialogue, extreme violence and endless homages to film genres of the past. The film features a predominantly female cast and boasts a lead female protagonist who frequently proves herself much stronger than the male characters in the film. The film was widely successful, with both volumes of the film taking in a worldwide box office total of $333.1 million. On the Internet Movie Database, males and females, aged 18-29, rate the film equally, with 8.2 out of 10 stars.

Females make up 52 percent of moviegoers, professor Martha Lauzen, who runs the annual studies for Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film, told the Times. But women don’t watch solely romantic comedies, as many industry executives seem to believe. “Kill Bill” is a testament to this: A film can be extremely violent and hugely successful at the box office, while still appealing to female moviegoers and boasting a cast of strong female characters. Not only should there be more females working in Hollywood, there should be more female protagonists, more weak male characters and more shifts in power between male and female co-protagonists. If Cate Blanchett has to preface her Oscar acceptance speeches with diatribes about sexism in the film industry, then you’re doing it all wrong, Hollywood.