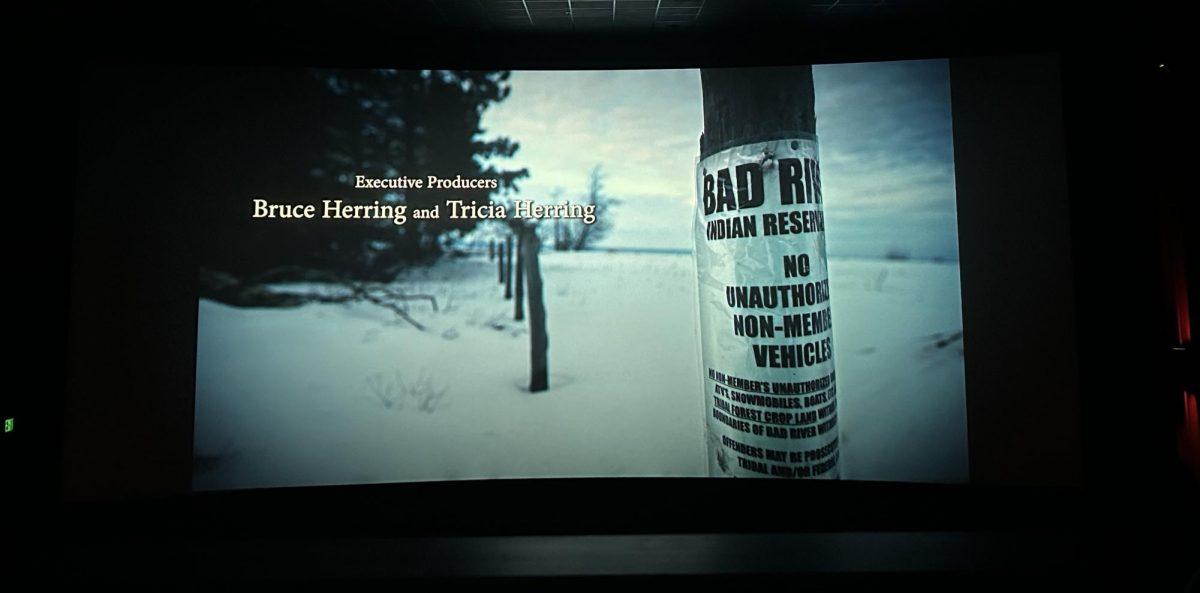

Roch Gersbach looks out the glass of the projectionist’s room down at the crowd of about 50 at the Cinematheque theater, located in Vilas Hall. The crowd, as usual, is made up of primarily older individuals, people who have spent years crafting sophisticated film tastes. The theater is small but intimate with a lavish, blue stage curtain, well-varnished wood walls and a couple hundred red cushioned chairs. There is a slight hum of conversation as the audience members read over their programs for the night’s film, “Classe tous risques,” a 1960 French thriller directed by Claude Sautet and starring Lino Ventura and Jean-Paul Belmondo.

Gersbach, a talkative man with an intense passion for film projection, continues to stare. He says nothing; this pause is noticeable respite from the preceding 20 minutes of conversation concerning nearly every facet of film projection – split reels, Dolby surround sound, aspect ratios, aperture plates, film emulsion, plastic versus metal reels, etc. The only noise in the small, cramped room is the steady roar of two 35 mm film projectors. Finally, he speaks.

“You have the cream of the crop of cinephiles here,” he says, still staring at the crowd. “A DVD or a tape is fine, but it’s only a souvenir of cinematic experience. You can’t beat watching it with other people. There’s just something about the social experience. It’s like going to church, you know? Like you’re all believing in the same guy.”

Since 1999, crowds have flocked to the Cinematheque to revel in classic and art house features presented in the highest quality film prints available. The University of Wisconsin was once home to a great number of film societies; during the 1970s and ’80s, there were sometimes 20 competing film societies in a given night, according to Cinematheque Director Jim Healy. But home video came along and these film societies went extinct. So, too, did the practice of watching movies on film in small theaters. The Cinematheque was founded by several UW film professors, including Lea Jacobs, David Bordwell, J.J. Murphy and others, to once again offer experiences in distinctly cinematic settings to both film lovers and novices.

The Cinematheque prides itself in its strict adherence to showing films on 35 and 16 mm film, both of which offer the highest possible image resolution.

“You’re going to see an actual film print the way it was meant to be shown and not some electronically-reduced format,” Healy said.

This practice is part of the Cinematheque’s dedication to taking film history seriously, Healy said. Because the Cinematheque doubles as a lecture hall, its films are couched in an academic setting. This isn’t a bad thing. Part of the Cinematheque’s mission is to foster audience discovery and reveal eras or artists to which a viewer might never have been exposed.

“What is life without movies”? Healy asked. “What is life without art? For me, the supreme art is movies. Once you’re in, you’re in. You’ve become committed. You’ll realize the possibilities of the art form. If you’re serious about being alive, then you should be here.”

As the majority of major movie theaters switch to digital projection and Hollywood churns out massive blockbusters designed to make profits above all else, many cinephiles are concerned that experiences like those offered at Cinematheque will become scarce.

Healy remains optimistic, noting that, while some practices of film viewing might be dying off, film viewing never will.

“Moviegoing isn’t what it used to be,” he said. “But at the same time, a lot of people do go to movies. So I think as long as there’s one movie that brings in millions of people every weekend, that means that people are still interested in going and having a theatrical experience. If there are people interested in movies, then I suppose there will always be an interest for discovery.”

For the spring season, the Cinematheque continued this dedication to audience through its numerous film series, including the films of Preston Sturges, rare John Ford films, Spaghetti Westerns (in honor of the recent “Django Unchained”) and the films of Studio Ghibli, which was co-founded in 1985 by acclaimed anime director Hayao Miyazaki. In July 2013, the Cinematheque will resume its screenings with films from French comedian Pierre ??taix, as well as a salute to Roger Ebert: a selection of his “Great Movies,” guilty pleasures and one he wrote in 1970, “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls.”

“People are there because they love movies and they’re there to enjoy movies and discover something,” Healy said. “You can really feel the energy from movie-loving in the crowd.”

Back in the projectionist’s room, Gersbach has two reels of “Classe tous risques” loaded into the two 35 mm projectors. When a reel runs out in one projector, it is Gersbach’s job to switch to the other one. It must be a seamless transition. Gersbach is eager to explain the process.

“I have to watch each and every reel,” he says. “There’s no warning, no buzzer, no bell. So, I have to watch, and when I start to see it get down to the end of the reel, I’m on the other machine – hopefully already threaded up so I don’t have to rush – sitting there waiting for the changeover mark. Then, I’ll start the projector. There’s a button over there that says start. I start that.”

He speaks of his craft with a hushed and excited reverence.

A woman who walks into the projectionist’s room is quick to say, “This is the best projectionist ever,” to which Gersbach says, “The best projectionist money can buy.”

Roch has been projecting films for nearly 35 years. He says he’s worked at all the theaters in town and proceeds to take his time listing off nearly 20 theaters in the Madison area for which he’s projected films.

“I’m not a film buff,” he says. “But I am a motion picture showman. I am the Picture Show Man.” He laughs.

Like art house cinemas, film projectionists are a dying breed, Gersbach says.

“A lot of archival prints come through here,” he says, “Which is the greatest thing that’s ever happened to me. There are no more union projectionists. They’re done. Everything’s gone to digital. There’s no film in theaters anymore. Everything’s automated. In fact, I don’t know if they even shut the equipment off. They just put it on standby. Then it kicks in the morning. So, there’s no showmanship anymore. That’s all gone.”

The clock strikes 7 p.m., and it’s time for the Picture Show Man to begin his work. He shuts off the lights in the booth, and the house lights follow. A brief crackle is heard on the film’s soundtrack before a lush, black-and-white image shoots upon the screen. The audience watches at the opening credits begin to roll.

For nearly two hours, the audience will sit there silently, watching as a strip of celluloid passes 24 images per second onto a screen in front of them. And until the lights come back up, the audience will have the chance to experience their feature as it was mean to be seen: on film.