As the United States nears another year of dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, the University of Wisconsin reopens for a third semester impacted by the deadly virus. With over 6,000 dead in the State of Wisconsin since the start of the pandemic and two vaccines now available for select populations, eyes turn to the UW administration, its students and Dane County to see where this semester will go.

To test or not to test

For Vice Chancellor of Student Affairs Lori Reesor, it’s all about testing.

In the fall 2020 semester, after an outbreak hit Southeast dorms Sellery and Witte in late September, UW Housing students had to complete regular tests to continue living in the dorms. But for everyone else — the large proportion who don’t live in or work with Housing — UW didn’t mandate testing at all. And while the rate of positive tests started to decline throughout the semester, over 5,735 students and faculty have tested positive to date through UW testing.

To Reesor, who described UW’s action plan for the spring in a press conference Thursday, testing and new technologies are key to curb outbreaks before they start. So for the spring semester, UW increased their testing capacity to roughly 80,000 tests per week.

“A high degree of testing, followed by quickly isolating and quarantining those who are exposed are key to keeping the university operating,” Reesor said.

This semester, students on campus and living in several off-campus zip codes in the City of Madison will have to test twice a week. Testing is drop-in and the app has live wait-time updates so students can drop by whenever it’s convenient to avoid long lines. UW will track test results through an app called Safer Badgers and if compliant with the test twice-a-week guideline, students get the green light to enter campus buildings.

If students living on or near campus aren’t compliant with testing guidelines, they could face student conduct consequences, said UW spokesperson Meredith McGlone. At first, the only immediate consequence will be that students will not have access to campus buildings. But, if they start to demonstrate a pattern of repeated violations, they risk consequences that could become more severe — starting with losing WiFi, the ability to add/drop classes, or access to transcripts with consequences growing more severe.

“If there is a pattern of missing tests, more serious sanctions could be applied. These can include disciplinary probation, which is part of a permanent disciplinary record. Disciplinary probation would be noted on a student’s transcript and would impact the ability to study abroad and impose other campus restrictions,” a statement from UW said. “It is possible that a student who is significantly non-compliant on COVID testing could be suspended. We hope such a step would be rare.”

Associated Students of Madison Student Council Chair Matthew Mitnick said these potential consequences are “ridiculous” because they do not account for extenuating factors influencing student’s personal lives.

“We’re not dogs, we don’t need a punishment or reward, this is just public health, we need to be responsible,” Mitnick said.

And, to add to the new testing requirements for each student, UW rolled out a new kind of test. While students living on campus will still receive the nose swab test at Ogg Residence Hall or the Frank Holt Center, other campus testing locations now feature a saliva-based PCR test. To complete this test, students drool into a small vial via a funnel at one of twelve locations across campus and can receive their results in around 24 hours, McGlone said.

Just like the nasal swab test from last semester, this test is PCR based, so it returns very few false negatives, McGlone said. For this reason, it’s different from the BinaxNOW saliva tests other UW System schools used last semester and more reliable.

UW’s basing their testing model this semester off the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, McGlone said. According to the UIUC COVID-19 dashboard, the campus kept its positivity rate under 1% for most of the semester, testing roughly between 3,000 and 10,000 people per day depending on the day, and returning under 100 positive cases a day — usually even below 50.

“Throughout COVID we’ve been paying close attention to what peers have been doing, to emerging best practices,” McGlone said. “And very quickly it became clear that the University of Illinois had a really good model, and so last semester folks began going down there to visit U of I, to talk to them to find out more about it. And that culminated in our decision to adopt their model, which a number of other institutions are doing.”

‘The test is not a cure’

To some students, like Madison senior and Amnesty International at UW Outreach Officer Gabrielle Santor, UW’s increased testing is too little too late.

“I feel this would have been an adequate response maybe two semesters ago,” Santor said.

While UW’s increased testing plan and Safer Badgers app may be new, student critiques are not.

After UW unveiled their Smart Restart this summer, student leaders across campus voiced concerns. In August, the Teaching Assistant’s Association released their Moral Restart, a revised COVID-19 protocol created to keep students and UW employees safe while putting “people over profit.”

The Moral Restart quickly received backing from the UW BIPOC Coalition, ASM and Amnesty International. While increased testing was one of the demands listed in the Moral Restart, TAA Co-President and UW PhD candidate in the Department of Neuroscience Alejandra Canales said solely focusing on tracking the spread is not an adequate solution.

“It’s good that there’s testing but people are still mostly going about their daily lives to go to class, to go to work,” Canales said. “The test is not a cure … it’s not actually something that’s a net benefit for that individual’s health.”

The Moral Restart goes beyond increased testing, demanding all classes be held online and all university housing be limited to students with no alternative housing options until Dane County meets the Public Health Madison & Dane County metrics for allowing in-person K-12 instruction to resume. These are among the several Moral Restart demands that remain unmet.

Santor said these unmet demands are what prompted the release of Amnesty International’s recent petition, backing the Moral Restart. While the petition was developed this fall, Santor said Amnesty chose to release it ahead of the spring semester after being “shocked” by the number of student demands UW has labeled “nonstarters.”

“I think they have a very singular view of handling the coronavirus which is only handling the coronavirus and none of the extensive byproducts and disadvantages that it’s posed to students,” Santor said.

One demand Amnesty included to address these “byproducts” was the reinstatement of a pass/fail option retroactively for fall 2020, as well as for spring 2021.

Julianna Bennett, UW junior and co-founder of the BIPOC Coalition, said pushing for pass/fail has been a frustrating process.

“The chancellor was quoted saying ‘there’s no evidence that students have been disadvantaged this fall,’” Bennett said. “That is wild, literally every single person on this planet has been disadvantaged this fall.”

Mitnick said UW’s first response to the pass/fail debate was creating a task force, which was a plan he initially felt apprehensive about, as he feared the force would not actually incorporate student demands — an issue he is currently working to address.

“As it stands the Faculty Senate is the one who has governing power over grading policies,” Mitnick said. “We’re trying to transition that to a task force with an equal student, faculty and staff representation because I think that is true shared governance.”

A seat at the table?

This push for student representation has been an ongoing battle throughout the Smart Restart vs. Moral Restart debate. In the fall, UW claimed they consulted students when creating the Smart Restart, despite an open records request filed by the University Labor Council that found no evidence of any surveys or attempts to poll student opinions on reopening.

UW’s spring plan works to address this lack of student input with the creation of a Student Advisory Committee for COVID Planning. The committee, which is made up of 11 students and currently has one open seat, was “structured to represent diverse viewpoints,” according to UW News.

Though UW invited students to apply, Mitnick, Bennett, Canales and Santor said UW didn’t notify any of their student orgs about the application.

“It’s a political grandstanding effort, where admin point to it and they say, ‘look, we’re listening, we have this committee,’” Mitnick said. “We’ve been requesting to have public comment at those meetings, to have it open to the public, which has yet to happen. I think that’s how you have an effective committee if the public drives those conversations.”

Bennett said the UW administration “cherry picked” the members of the advisory board, intentionally excluding the strongest advocates for the Moral Restart. Bennett did say the BIPOC Coalition has made progress on overall communication with administration. They have now met with Chancellor Rebecca Blank once and are in the process of scheduling a follow-up, after the Chancellor refused to meet with the coalition throughout the fall.

This lack of student input is reflected by UW’s current COVID-19 plan, according to Bennett, who said the plan’s failure to mention BIPOC students ignores how underserved this population has been and continues to be at UW.

Bennett said UW’s spring plan actually places more of a burden on students of color, forcing everyone to get tested indiscriminately puts BIPOC students at risk, as data has shown significant racial disparities in COVID-19 cases. Bennett said most of the BIPOC students she knows stay home and are diligent about quarantine guidelines.

“Just to center BIPOC needs again, a lot of us are essential workers and a lot of us have families we need to attend to, we can’t get COVID,” Bennett said. “That’s one of the main concerns around requiring people to get tested because they’re basically just forcing people to go out and expose themselves.”

In the media briefing last week, Executive Director of University Health Services Jake Baggott addressed concerns pertaining to transmission at testing sites.

“We’re learning where we’re seeing testing demand in higher numbers and making adjustments to mitigate that,” Baggott said. “We have a lot of experience with testing sites and we’ve taken the experience we’ve learned there … and have adopted those protocols in spacing and timing to limit the potential risk there.”

The frequency and the high volume of students at these testing sites has been a concern across campus. UW has already switched from appointment-based testing to drop-ins after receiving feedback about long wait times.

Despite these efforts to make testing more accessible, Mitnick said UW’s spring plan remains inadequate.

“The only thing that they have really implemented from that statement [the Moral Restart] is increased testing,” Mitnick said. “The same concerns apply, the same issues with lack of access to adequate healthcare or resources for studying whether it be in-person or online, are still there.”

Agreeing to disagree

For Dane County Executive Joe Parisi, UW’s spring plan is missing the acknowledgment that campus is a part of the greater Madison community.

This fall, Parisi and Blank received attention after a flurry of contentious press releases and public statements debating UW student’s impacts on the wider Madison community. While Blank said Dane County “is where students live” and it’s unacceptable for Parisi to “simply wish them away,” Parisi’s office expressed concern over rising COVID-19 rates in the downtown area.

“I think that was a bit of victim blaming,” Parisi said. “Before the university came back, we expressed to them that we had concerns about them coming back and that we had concerns about our capacity, which was already being stressed by the virus … You can’t really say ‘I’m gonna bring 40,000 people downtown’ and then wash your hands of any responsibility for their actions afterwards.”

While Parisi did say he believes the university is better prepared for the pandemic this semester, he continues to disagree with the university’s decision to bring students living in dorms back for the spring.

“I would like to see the dorms not reopen and then to give those students the opportunity to work remotely,” Parisi said. “Obviously we know there are very safe practices taking place in the classroom, but we can’t control what people do in congregate settings like we find in the dorms.”

Despite a decrease in COVID-19 cases on the UW campus in the latter half of the fall semester, Dane County saw a lasting negative impact after students returned in August and September.

According to Public Health Madison and Dane County’s COVID-19 Dashboard, after the county’s positivity rate remained at or around 2% from July 1 through Sept. 2, the positivity rate has not fallen below 2.8% since Sept. 5, even reaching as high as 10.6% from tests on Nov. 12.

PHMDC Communications Director Sarah Mattes said the department hopes the new precautions and increased testing capacity of the university will prevent another spike in cases in the county this spring.

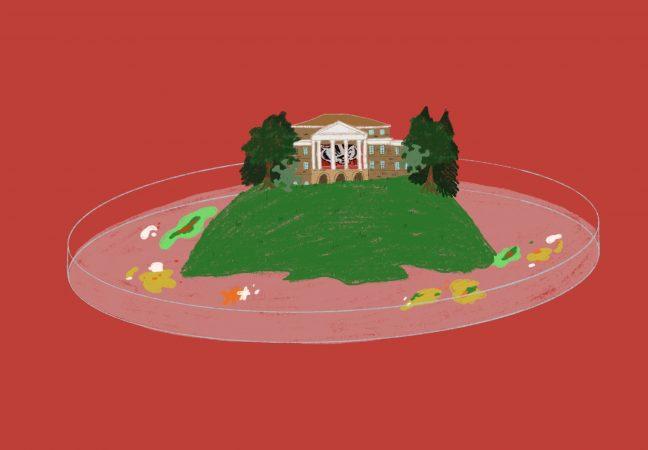

“More testing helps us stop the virus in its tracks sooner, but UW-Madison is not an island,” Mattes said. “An increase in cases on campus may impact the surrounding community. We’re hopeful these additional precautions prevent a spike from happening on campus and in our community, but we can’t speak to whether this plan will be enough to avoid another increase in cases.”

District 5 Dane County Supervisor Elena Haasl and District 8 Alderman Max Prestigiacomo — both of whom also attend UW — said they believe the spring semester plan, while better than the fall plan, still has issues.

“I think that they put more thought into the plan this time around,” Haasl said. “They’re trying to make campus safer but I’m still a little concerned about the dorms and move in.”

Vaccine-ready

When the FDA approved the Pfizer BioNTech and Moderna mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in December, the country let out a breath. With high efficacy rates, many across the country finally allowed themselves to see the light at the end of this dark tunnel. But approval was only the first step and now states like Wisconsin must reckon with distribution.

On Jan. 5, UW administered its first COVID-19 vaccines to workers through University Health Services. UW received roughly 1,000 vaccines from the Wisconsin Department of Health Services as their first allocated batch of vaccines. Right now, in Phase 1a of the statewide vaccination plans, only frontline healthcare workers, as well as long-term care workers and residents are eligible. For Phase 1a, UW plans to vaccinate roughly 2,000 people.

Devlin Cole works as a preventative medicine resident at the UW School of Medicine and Public Health and received one of the first vaccines on the UW campus. As someone who worked to curb the pandemic on college campuses as a part of a joint initiative with the CDC, Cole reported feeling “elated and honored” when she got the vaccine.

“I’m thrilled that we’re able to be protecting a lot of people on campus as we move forward,” Cole said. “I think this shot really represents hope, especially for a lot of people in the healthcare field, because we have really seen the toll that it’s taking both locally and in the country and abroad. This is the first step towards returning back to an in-person connection where we can hug people and shake hands.”

When vaccines could be available to the UW student population at large is anyone’s guess, as Wisconsin works through its tiered distribution plan which places more vulnerable populations earlier in line for a vaccine. Plus, UW can only administer as many vaccines as the state gives them. While they’ve been distributing about 250 per day, Cole said the rate could change in the coming months as the state decides how many doses to allocate to UW.

Moving forward

Industrial Engineering Professor Oghuzan Alagoz has been using computer models to track trends in Dane County since the beginning of the pandemic. Coming into spring, he said he feels optimistic about the university’s increased testing plan and the possibility of a vaccine curbing another outbreak.

But any progress towards keeping cases down could fall apart if students and the surrounding community don’t continue to social distance and wear masks throughout the semester, Alagoz said. Only once most people get the vaccine should COVID-19 protocols start to relax, which could be months from now.

“Just because a vaccine is available doesn’t mean that we should take it easy and immediately go back to business as usual, because that definitely is going to lengthen the time until we are out of the woods,” Alagoz said. “We should not stop following these guidelines and recommendations, and we should still wear masks.”