In an event Wednesday, the Clean Lakes Alliance hosted an information session on the dangerous levels of algae that have been reported in Madison-area lakes in recent weeks.

The session was led by Katherine McMahon, a civil and environmental engineering professor at the University of Wisconsin. She informed the Madison community on the blue-green algae that have filled Madison-area lakes this summer.

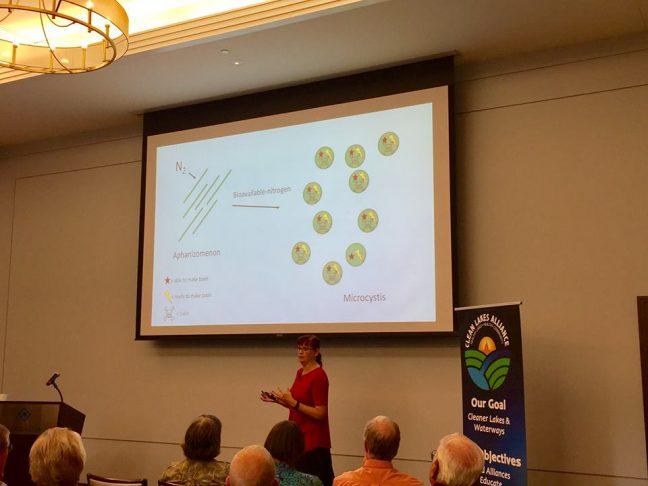

Blue-green algae, or cyanobacteria, grows under light exposure when there is an unbalance of phosphorus and nitrogen. Exposure to the algae can create vomiting, headaches, fevers and diarrhea.

“Right now, if you’re at a beach and the beach is supposedly open, but it starts to look blue-ish green — don’t go in it,” McMahon said. “We can’t tell you if it’s safe or not.”

Although there have not been many human fatalities from the algae, McMahon said there are many cases of dogs dying from it. She addressed the safety concerns of swimming in the lake, and warned the algae could create liver toxins and neurotoxins.

McMahon suggested checking Madison’s Lake Forecast before swimming. However, she said the site’s warnings may be conservative due to a lack of lab testing.

UW suspends Kappa Sigma after falling television nearly crushes woman at party

McMahon explained that testing the water costs $250 per sample and that regular testing is not realistic, as it takes multiple days for lab results to come in and only a few labs can run the necessary tests.

“The lake might be in a different condition from when you collected the sample,” McMahon said.

McMahon said toxin levels are hard to measure and not all blue-green algae is toxic. Sometimes only one third of blooms create a toxin.

Cyanobacteria, which is different from green algae because of its higher levels of phosphorus and cyan, builds up toxins that are released when the algae blooms die.

“On average, these compounds contain more nitrogen than you may expect. It’s something that’s always puzzled people — why an organism would invest so much effort in making these complex structures,” McMahon said. “They’re wasting a very precious resource by making this stuff.”

Specific toxins to be worried about, according to McMahon, are microcystin, cylindrospermopsin, saxitoxin and anatoxin.

Although Lake Erie has some of the highest cyanobacteria levels, Lake Winnebago is the highest for those near Madison, with a specific increase of microcystin. Lake Menona and Lake Mendota follow Winnebago.

“If you drink the water, whether or not the cyanobacteria is alive, [algae blooms] will burst inside your body or your dog’s body,” McMahon said.

Catherine Lyman, a Madison resident, expressed concerned about blue-green algae in beaches designated for dogs. CLA said they are working to regularly monitor all beaches.

Report finds no criminal liability against UW in Lake Mendota windsurfer death

And although the blooms are harmful, McMahon said toxin concentrations rarely exceed the World Health Organization’s levels for safe drinking water.

“Our lakes have the opportunity to be more eco-friendly, more sustainable,” said James Tye, a member of CLA.

McMahon said community members and students can help make a difference too. She suggested encouraging more phosphorus-reducing projects to combat the spread of the algae.

Adam Sodersten, director of marketing and development at CLA, said students can combat the spread of blue-green algae by raking leaves in the fall. He said water runs through leaves and takes phosphorus with it.

“Reducing any kind of run off” is helpful to lakes, Sodersten said.