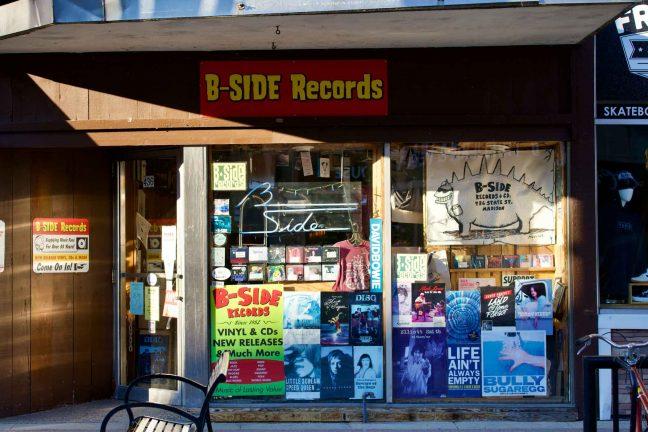

JD McCormick Properties presented their proposal for a new housing development on State Street to the Urban Design Commission Feb. 9. The plan includes 23 to 26 apartment units and some public fixtures, such as a restaurant and a place for murals. Controversially, these developments would replace Sencha Tea Bar, B-Side Records and Freedom Skate Shop, which are some of the most beloved local businesses and icons on State Street.

JD McCormick representatives argue their development is intended to bring modern elegance that would help revamp State Street for Madison residents. They insist that the project would be a positive cultural addition to the area.

Meanwhile, some citizens worry how the displacement of local businesses could impact the culture of State Street. For many residents, small businesses are crucial to the identity of the city. Cultural landmarks like B-Side Records represent Madison’s interests and values, and losing this business would inevitably upset local residents.

More generally, small businesses like these provide a critical sense of community often lost when larger companies take over. Without them, there is a shift in local influence to larger corporations that are more likely to lose touch with the community.

Some citizens hold reservations about the JD McCormick proposal in particular. The apartments — considered “elegant” — may not be tailored to the specific housing needs of an area near the University of Wisconsin campus. District 8 Alderperson Juliana Bennett said the current average rent price of $800 per person is unaffordable for many UW students, many of which live in the State Street area.

With all of this in mind, it is difficult to discuss this issue without understanding the history of housing discrimination in Madison. Patterns of redlining from the early twentieth century are still identifiable on housing maps. This, coupled with rampant gentrification in the successive decades, has harmed lower-income residents who are forced out of their neighborhoods.

The State Street and Capitol Square neighborhoods in particular are considered to be completely gentrified. This means that though the area was once home to a population of financially disadvantaged and diverse residents, the neighborhood has seen a significant increase in college graduates and a decrease in people of color. In other words, people and businesses living or renting in the area have been displaced for decades as real estate developments replace older, relatively affordable housing.

According to a report on equitable development in Madison, the Capitol Square and State Street area are labeled as “appreciated.” Not only does this mean that they have been entirely gentrified and are no longer affordable according to general standards, but prices are still increasing.

This phenomenon should be cause for concern considering that displacing people and businesses can be deeply harmful to communities. It also poses challenges for people who take public transportation but are pushed out of downtown Madison to the edges of the city where it is less reliable.

On the other hand, economic principles of supply and demand demonstrate that creating more housing can decrease scarcity and prevent prices from becoming unaffordable in the first place. By this logic, building more apartment units on State Street would help mitigate Madison’s housing shortage, which is contributing to expensive buying and renting costs for residents.

According to UW Urban Planning Professor Kurt Paulsen, with the addition of apartment units that will be rented at or above market value, housing demands will be met and prices will drop in certain situations. Though the JD McCormick development could be unaffordable for some residents, increasing supply could help balance market forces in the long run.

This strategy was effective in the Tenney-Lapham neighborhood of Madison, a district located northeast of the Capitol Square. This area originally housed a mix of owners and renters. The construction of several multi-family buildings shifted demand away from older homes, who then had to compete with pricing. As a result, rent costs have increased at a slower rate than the city average, keeping the area affordable.

In order to balance these economic issues with gentrification concerns, what is the best solution? Realistically, with just 23 to 26 primarily studio apartment units, it seems like JD McCormick’s development is unlikely to create enough of a supply to meet the demands of the city or have much of an impact on housing affordability. Construction at the planned location, however, could still harm the community with the loss of beloved local businesses.

Ultimately, Madison needs more housing, but JD McCormick’s development alone is not going to solve this issue. Larger public policy initiatives sponsored by the city government would be more likely to take root in Madison’s deeply gentrified neighborhoods. The Equitable Development Assessment suggests that measures such as eviction protections, housing subsidies and inclusionary zoning could help protect residents and businesses as developers aim to meet city demands.

Housing discrimination should not be viewed as an issue of neutrality, because almost every decision benefits or harms those disadvantaged by centuries of exclusion. Without considering the potential for gentrification in housing decisions, we could be perpetuating conditions of discrimination deeper into permanence.

Celia Hiorns (hiorns@wisc.edu) is a freshman studying political science and journalism.