Scientists at the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene are partnering with UW-Milwaukee researchers and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources to conduct statewide testing of sewage samples for COVID-19 after receiving a $1.25 million grant from the Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

The partnership aims to develop sewage testing into a tool public health officials can use in tracing the pandemic as it spreads through local communities in Wisconsin, according to a DHS press release. The release added sewage testing could potentially be used as an early warning system to anticipate COVID-19 flare-ups.

In principle, the widespread COVID-19 nose swab tests and the sewage test work the same way. Both tests must separate out genetic material, which is tested for the presence of genetic code specific to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, Sandra McLellan, an environmental virologist leading the UW-Milwaukee team, said.

But obtaining genetic material from a sewage sample is the challenging part, McLellan said.

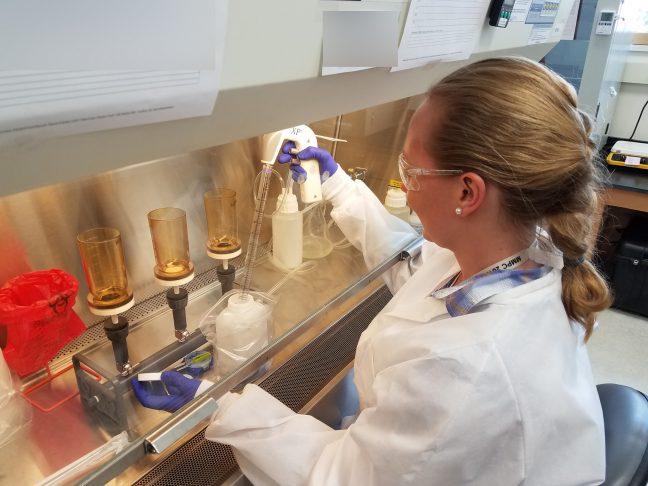

According to WSLH researcher Kayley Janssen, wastewater plants first filter out large solid particles from incoming sewage. The resulting water is sampled over 24 hours to produce a bulk composite half-liter sample which is sent to the researchers.

Using a variety of filtration methods, the researchers end up with 50mL of liquid from which they extract genetic material.

Sampling wastewater from sewage treatment plants is meant to be complementary to human testing rather than a replacement, Jon Meiman, one of the DHS’s chief medical officers, said.

New order requires all Dane County residents to wear masks in public

“Anytime we do disease surveillance, we like to look at a particular disease from as many angles as possible, since no one particular approach is going to give you the whole story,” Meiman said.

Data from the sewage tests could be used to assess confidence in ongoing individual testing. If the data from sewage testing points to ongoing transmission in an area where individual testing turns up little to no cases, it could indicate the virus is spreading among a demographic that is not being tested, Meiman said.

For instance, young people who are less likely to be symptomatic are also less likely to get tested but will nonetheless shed the virus into the wastewater system, Meiman said.

Historically, the idea of testing for pathogens in sewage is not without precedent. For over half a century, scientists have used it to trace outbreaks of polio.

New Dane County social distancing restrictions announced as COVID-19 cases increase

McLellan said many in the field began thinking of wastewater testing as soon as the virus emerged.

A Dutch group was one of the first to put the idea to the test. In late March, they published research showing detection of the virus in sewage up to six days before the first reported case in some rural areas.

Some European countries are now investing heavily in the idea. The Netherlands, Germany and Finland scaled up sewage testing into national early-warning systems.

Places across the U.S. also began to invest in the approach, McLellan said.

“North Carolina, New York City, California and many other places have large regions that are coordinating and trying to get a surveillance program up and running,” McLellan said. “I would say almost every major city is thinking about this or actively trying to set it up.”

The team hopes to eventually have regular, weekly sewage testing from 100 different wastewater treatment plants, 80 of which will be in rural Wisconsin, Janssen said.

Janssen said sewage testing helps in rural areas because they don’t always have access to nose-swab tests.

“Some of those communities don’t have the same access to testing that we do in Madison and Milwaukee,” Janssen said.

Early results from samples taken in May in Milwaukee, Racine and Green Bay show viral concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 hovering at the lower limit of the researcher’s detection ability, McLellan said.

The researchers are working on optimizing their method to try to detect even lower concentrations, McLellan said.

“The samples we’re analyzing are from when there were a lot of stay at home orders and people were not really emerging into the community and mixing with a lot of other people,” McLellan said. “As we go forward, I think we want to keep a close eye to see if those numbers go up.”

Wisconsin Union Terrace to open June 22, with COVID-19 restrictions

Using sewage testing, a few other states were able to predict local COVID-19 surges in advance, providing crucial time for shifting resources and ramping up public health responses, Meiman said. Because testing capacity remains limited, it could be targeted towards areas where flare-ups are anticipated, Meiman said.

The director for the National Institute of Health said recent delays in testing reduced their usefulness as a tool for stopping transmission.

“The idea is that we can pin down that trajectory before things become too far gone, because by the time we start seeing a large number of cases, the actual size of the epidemic is much larger than we know,” Meiman said. “We’re looking at the tip of the iceberg, and we’re seeing that in the Southern United States right now.”