Brandon Shields had to consider a cost most students don’t have to think about when deciding to attend the University of Wisconsin for his Master of Business Administration — the price of childcare.

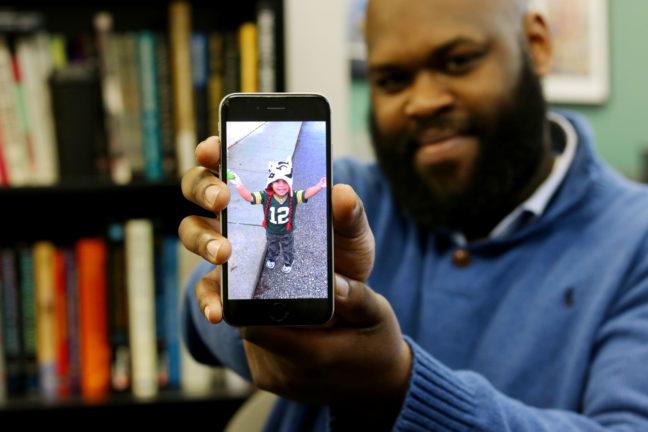

Shields is among a group of both graduate and undergraduate students who balance being full-time students and the responsibilities of parenthood. Before he even set foot on campus, Shields began researching the services available and placed his 2-year-old son on the waitlist for a child care facility near campus.

According to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, the number of student-parents in the United States rose by 1.1 million, or 30 percent, between 2004 and 2012. In the Great Lakes region, there was a 21.8 percent increase in student-parents.

“I’m not even sure students even realize there are parents among them, especially in the undergraduate ranks,” Shields said.

Since its creation in 1985, the UW Office of Child Care and Family Resources has worked to connect student-parents to services like child care and the Child Care Tuition Assistance Program, which provides funding for parents who have children in Wisconsin child care programs.

Navigating through campus child care

According to its website, OCCFR helps to coordinate the six different UW child care programs, three of which are located near campus. Shields, whose son is enrolled at Eagle’s Wing, a facility managed through University Apartments, said as a single father, day care services are essential.

The School of Human Ecology houses the Preschool Laboratory, a child development and early learning program for children of students, faculty, staff and the greater Madison community. They provide services for children ages 6 weeks to 5 years old.

Paula Evenson, an assistant director of the Preschool Lab, said apart from offering child care programs, the lab acts as a teaching and research program for students and faculty. Currently, there are 100 children enrolled in the lab. Many new infants begin during the start of the fall semester.

“There is support certainly for faculty or staff or students who work here,” Evenson said. “A lot of families here are affiliated with the university. We hear frequently that it’s super convenient for them.”

Julie Kallio, a doctoral student in educational leadership and policy analysis, has her 4-year-old and 15-month-old sons enrolled in the Preschool Lab.

Since Kallio does not have family in Madison to help her take care of her kids, she enrolled her two sons in the program full-time. While access to child care was not her primary concern when choosing a university, it was a factor.

“[Child care] was sort of a piece of the puzzle that I knew I would have to figure out,” Kallio said.

UW student looks to reshape concept of motherhood, help marginalized mothers

Evenson said the lab is open to the whole Madison community. No priority is given except to currently enrolled families who want to bring siblings.

On campus, Evenson said child care is one part of the support network for faculty, staff and students, but there is no way to hold a spot for members of the UW community. One common issue is a need for more child care locations.

“There’s a really high need for infant care on campus, but not enough spots,” Evenson said. “We usually have a really large waiting list here.”

Evenson said one of the goals of the OCCFR office is to expand infant care options. But as soon as Eagle’s Wing expanded care for infants, the Preschool Lab closed its second location on Mineral Point Road.

Both Shields and Kallio noted while the child care services at UW are accommodating, it’s expensive to enroll their children. Kallio said tuition in the baby room of the Preschool Lab is around $12,000 a year, so for two kids, it can be a lot of money.

Shields gets a slight discount since he lives in Eagle Heights, where his son’s day care facility is located, but it can still cost $7,000 to $8,000.

“I don’t pay to go to school,” Shields said. “I pay more for my son’s education than I will for my MBA.”

To help with the cost of child care, CCTAP provides financial assistance to income-eligible student-parents for child care expenses. The students can receive assistance for up to three children ages 0 to 12 as long as the child care providers are in Wisconsin. Both Shields and Kallio receive funding from CCTAP to help support their children.

Through support from non-allocable segregated fees, CCTAP can fund about 200 to 300 student-parents each fall and spring semester and 100 each summer session. All funding is on a first-come, first-serve basis as long as eligibility factors are met.

Student groups unite in effort to oppose contentious budget proposal

Finding housing

Since Kallio owns pets, she is unable to live in the Eagle Heights or University Houses neighborhoods, where many graduate school families stay. Shields, on the other hand, lives in Eagle Heights with his son.

Brendon Dybdahl, Division of University Housing spokesperson, said the apartments in Eagle Heights are the main way university housing serves student-parents. Most Eagle Heights residents are graduate students or Ph.D. candidates, but some undergraduates with children also live there.

For Shields, living in Eagle Heights means he gets a discount for Eagle’s Wing day care. He said it’s convenient for the day care center to be within the community.

In both Eagle Heights and University Houses neighborhoods, Dybdahl said 2 percent of the residents are undergraduates who are either married and/or live with a dependent.

Beyond Eagle Heights and University Houses, Dybdahl said there are no other housing or child care services managed through University Housing. Since only enrolled undergraduate students can live in the University Residence Halls, spouses or children cannot live with a student.

If a child or spouse were to come visit a student in a residence hall, Dybdahl said they would face the same restrictions as typical guests. According to University Housing policies, overnight guests cannot stay with a student in any hall for more than three consecutive nights, six nights per month or two weekends per month.

Dybdahl said most universities across the country do not allow nonstudent family members to live in undergraduate residence halls.

“Residence halls are designed for adult undergraduate students of the university to support academic success and connections to fellow students,” Dybdahl said. “Nonstudents would disrupt that focus and would reduce the number of spaces for undergrad students who want the on-campus living experience.”

Juggling school and family

Kallio said kids are often unpredictable. When one of Kallio’s kids was sick, she stayed home while trying to manage her school group and ended up not finishing her statistics homework.

Kallio had her son while she was in graduate school. Since she was in the School of Education, she said there was a high percentage of females who had been pregnant in the past, so they understood what she was going through.

But there is no official maternity or paternity policy for graduate students at UW. The University of California–Davis has a policy that during a pregnancy, a student may receive a maximum of six weeks leave.

Kallio said she thinks having those policies in place at UW could be helpful in the future. She also would like to see a play space, where kids could stay during the day, in one of the unions.

One of Kallio’s fellow graduate students does not have child care, so she pays a student to watch her child while she’s teaching. They roam and hangout in hallways since there is no designated place for families or parents to go on campus.

While having kids forces Kallio to miss some meetings, she said one of the benefits is better time management. When she picks up her kids after school Friday, she focuses on them and doesn’t work from Friday afternoon to Sunday evening.

“I think that’s a break most people don’t get,” Kallio said. “It makes me very deliberate with my time during the week. I think it made me have a healthier balance with school.”

Like Kallio, Shields found a balance between school and family. Even after being on campus for a while, he finds resources he didn’t even know about that help student-parents.

Before coming back to school for his masters, Shields spent the last six and a half years working in the military, but left to provide better opportunities for his son. After coming to UW, he became inspired to work on a startup idea that could help other student-parents find child care after he worried about who could babysit his child in a new place.

“I knew that if I got an MBA that it would lead me to have the kind of life that I wanted and give me the means to provide for [my son] in a manner that I thought he deserves,” Shields said. “Coming here has allowed me to achieve those goals.”

Shields said family is always a priority, so when his child gets sick and can’t go to day care, that means he’s staying home and will need to make up his school work somehow. He tries to get all of his school work done before 4:30 p.m., when he picks up his son.

Since he needs to make the most of his time, an hour of Shields’ homework time equates five hours for other students.

“When I am home it’s just about us,” Shields said “It’s not daddy reading books or working on problems while baby is off in a corner by himself. As soon as I leave school I’m dad. I’m just dad.”