Cryopreservation has helped researchers develop vaccines and treatments during the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing monkeypox outbreak.

According to the National Library of Medicine, cryopreservation is a technique often used in labs to study anything from smaller samples like bacteria and viruses to larger samples such as tissues. The method involves carefully freezing and preserving samples for later experiments or observation.

The technique helped COVID-19 and monkeypox researchers learn how the viruses functioned on a molecular level.

According to University of Wisconsin Department of Bacteriology assistant professor Kerri Coon, early on in the pandemic scientists had to scramble to find ways to study COVID-19 in the lab. Partly because of cryopreservation, scientists were able to grow the volume of information they had on COVID-19 to where it’s at now.

Graduate student Kendra Gallo in Mostafa Zamanian’s lab said investigators of the ongoing monkeypox outbreak also conducted a lot of their research using cryopreserved samples of smallpox, a virus closely related to monkeypox.

The smallpox virus is preserved in biobanks, or collections of preserved or frozen biological specimens, according to the World Health Organization. Though it was eradicated over 40 years ago, keeping samples helps researchers develop better treatments and vaccines for smallpox or related diseases, Gallo said.

Outside of COVID-19 and monkeypox research applications, cryopreservation is a common technique among other areas of research, Coon said, whose lab also relies heavily on cryopreservation.

For example, researchers who want to study a particular gene may conduct cloning experiments with nonpathogenic strains of E. coli, a standard laboratory model bacterium. In the UW Microbial Sciences Building alone, Coon said every lab has preserved stocks of E. coli because of its importance to central molecular techniques.

Recent study finds how principal investigators influence lab culture

Specifically, Coon’s lab focuses on understanding the diversity and function of gut bacteria in mosquitoes’ and other insects’ ability to spread disease. To do this, Coon said researchers must have large collections of bacteria and fungi from different places that can be easily grown in the lab.

Coon and the rest of the researchers in her lab use cryopreservation every day mostly to check the consistency in their experimental work, Coon said. Without it, Coon said she’s not sure it’s possible to continue her research at its current level of rigor.

“It’s very hard to study things from a functional standpoint when you’re only working in the field … So in order to be able to study those field-derived microbial communities and genotypes, we have to cryopreserve them so that we can come back to the lab and study them in the lab under controlled conditions,” Coon said.

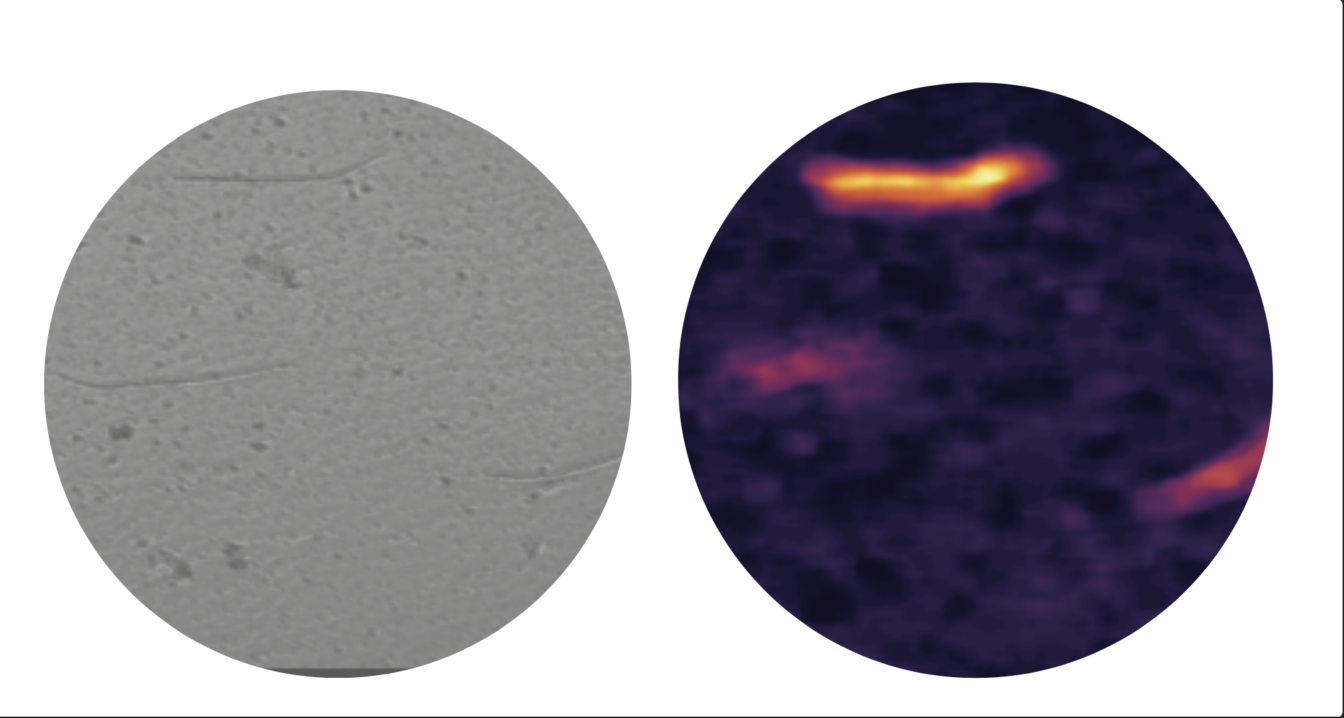

Similarly, Gallo said the Zamanian Lab studies nematodes, which are worm-like parasites, and cryopreserves them at different stages over time.

Science Magazine editor-in-chief on how science ‘lost’ America, how to gain it back

Cryopreserving nematodes at different life stages doesn’t kill the parasite. In fact, after thawing the samples, a completely revitalized, healthy nematode remains, Gallo said. Through this process, the lab’s research aims to maintain and preserve the RNA of the parasites to find new cures for the diseases they cause.

“For the Borgia parasites, we have animal models that we can get parasite tissue from, so we can get different stages of parasites in the lab to do research,” Gallo said. “But for Mansonella [parasites], we don’t have that established and so really the only way to study this is to cryopreserve those parasites.”

Cryopreservation also provides benefits for replicating experiments. Gallo said reproducible data in science is very important, which is something cryopreserved parasite stocks at different stages provide. This way, if a different lab wants to replicate an experiment, it has the nematodes it requires at a particular life stage.

The notion of having biobanks and stocks of harmful and parasitic microorganisms like smallpox and nematodes might be worrisome for others. But there are strict and extensive regulations in place everywhere harboring cryopreserved samples including annual biosafety checks, Coon said. This standardization of biosafety guidelines across labs in the U.S. ensures facilities are managing samples appropriately and responsibly.

Both Coon and Gallo said they personally think the benefits of cryopreservation outweigh the possible risks. They also said while there are other ways to conduct parts of their work without cryopreservation, it would be difficult. It would also hinder the quality of the results through frequent sampling and resampling, Coon said.

There is always the potential for someone to use science in harmful ways, Gallo said. When it comes down to it, it is about scientists individually finding ways to conduct their research ethically by assessing its potential.

“As scientists, it’s important that we think about what we’re doing and the potential harm that it could cause, even though that’s not our intention,” Gallo said.