For the thousands of University of Wisconsin students who attend Madison's Halloween celebration every year, participation in the State Street festival is simply a given — but it was not always that way.

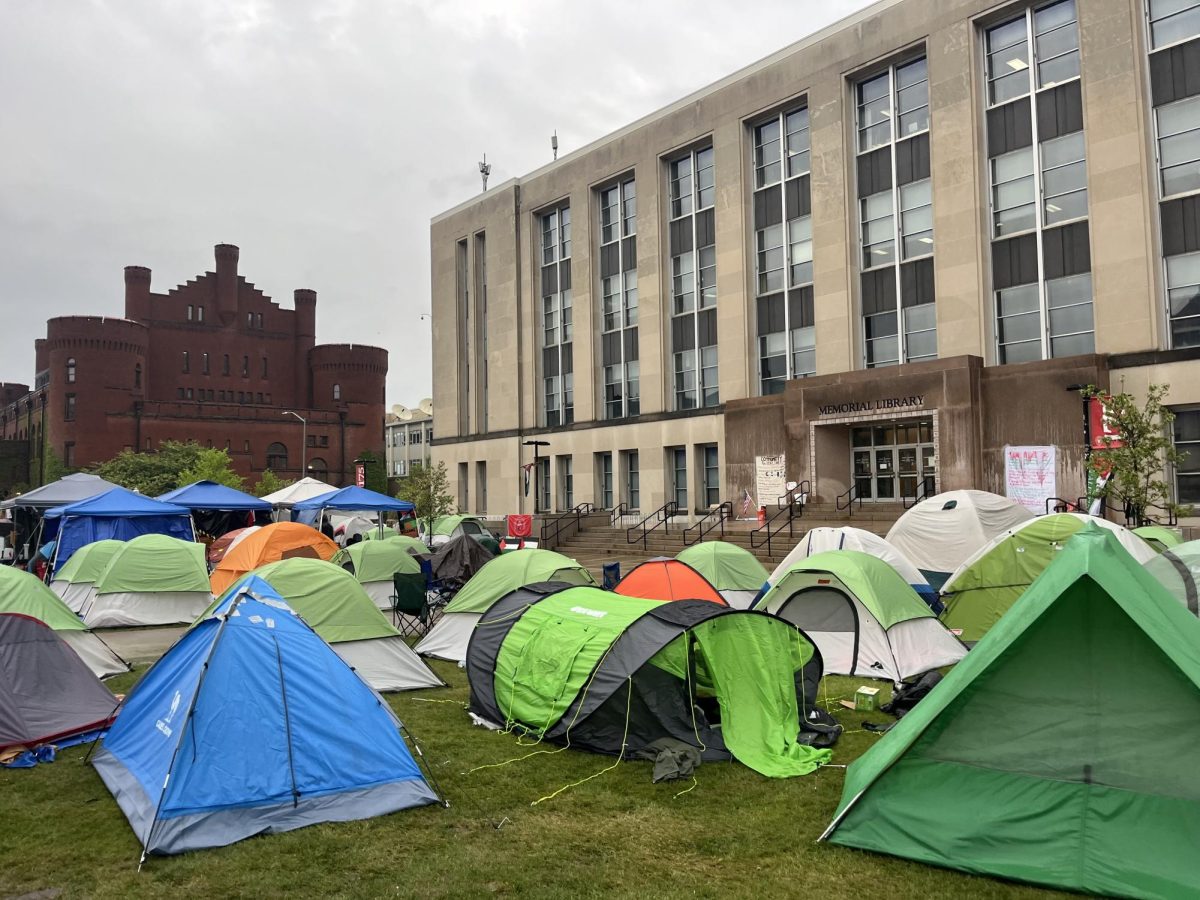

From the party's roots as an event organized by the university's student government that included beer gardens throughout Library Mall to its current modifications, which will barricade the party and include an admission charge, Halloween in Madison has been no stranger to its fair share of changes.

"[Halloween] has ebbed and flowed in so many ways," Ald. Mike Verveer, District 4, said. "Every year seems so wildly different in terms of crowd size and behavior. Like with other things, it has had its good, bad and ugly."

Verveer recalled his days as a UW undergraduate, saying his attendance at the annual Halloween party was not only memorable, but "awesome." He acknowledged its emergence as an event, ushering in changes good and bad alike over the years.

History

According to a report compiled by UW Communications by request of Chancellor John Wiley, the "infamous celebration" of Halloween in Madison began in 1977 when a large group of people — roughly 5,000 — gathered on State Street to celebrate the holiday.

The group ultimately formed a mob and began throwing bottles from rooftops and building fires, not unlike other occurrences that would later be typical of the Halloween parties from 2002-on.

Following the initial Halloween gathering, the event continued to gain popularity and boasted a growing turnout. In 1979, the student government — then the Wisconsin Student Association — sponsored a party corresponding to the State Street event in hopes of lending more structure and less rowdiness.

Despite a costume contest, live bands and organized alcohol sales, the party failed to shed its unruly nature. Arrest totals climbed year to year and an increased police presence was utilized to douse fires, pull partygoers from the tops of lampposts and control the crowds.

The 1980 party saw a turnout of 30,000 people, a police presence of 70 officers, 10 arrests, a cost to the city of more than $16,000 and injuries that included two officers needing treatment "after being bitten by a person."

For the next two years, crowd sizes numbered around 100,000. In attempts to curtail pole climbing, police greased light poles and even installed some that would collapse under heavy pressure. Police presence escalated.

Yet despite the increase in city planning, a similar atmosphere prevailed. Injuries included hospitalizations due to trampling and stabbing, and in 1983 — what has been dubbed as the most tragic Halloween celebration — one man died after falling from the roof of a building on the corner of Lake and State Streets.

In 1986, the student government decided not to serve beer, possibly because of the state's new drinking age of 21. That did not, however, curb the boozing.

The report by University Communications cited an officer saying, "When they sold beer, at least a few people would only drink one or two, now they're all walking around with six or 12."

The following year, the student government again offered beer, this time from two beer gardens set up with restricted access. While they spent $25,000 on alcohol, not even half of that was recovered in sales; the student government thereafter discontinued sponsorship due to expense.

"They tried less expensive things like putting on non-alcoholic events at the Field House and Bascom Hill … and concerts on Library Mall," Verveer said. "They tried to cover their costs … but they were not very successful. In the end, the costs were just too overwhelming."

The following years saw a lull in the turnout for Halloween, with few remarkable incidents reported — save for a scare in 1998 when a rumor surfaced among students about a mass murderer dressed as Little Bo Peep.

But Halloween as it is known today, and with the turnout typical of the earlier parties, came back to State Street in full force at the turn of the century.

"For some years it wasn't that big of a deal … but all it took was some beautiful weather one year," Verveer said, recalling being present at a police command post near State Street. "I'll never forget the cops freaking out because they had not expected that level of crowds. That hadn't happened in years."

From then on, Halloween began to take shape as it is known today. Although crowd size has not reached numbers seen in the 1980s, turnout in recent years has been estimated at nearly 80,000.

Where the initial events included limited city planning, few arrests and a city cost of roughly $25,000, the 2005 Halloween celebration was markedly different.

Last year's event saw bright stadium lights and a loudspeaker system, a significantly increased police force, banning of out-of-town guests in University Housing, 468 arrests and 700 total citations, and a combined city and county cost of about $500,000.

How does Madison Mayor Dave Cieslewicz feel about this year's event?

"Cautiously optimistic," he said.

Not alone

While Madison's annual Halloween party is a unique time for UW students, Madison residents and out-of-town visitors, the city is not alone in hosting large-scale holiday celebrations.

Chapel Hill, home to the University of North Carolina, hosts a Halloween event that attracts up to 70,000 partygoers every year.

Located on Franklin Street, similar to Madison's State Street, the party shares common themes with the Halloween celebration in Madison.

While the violent nature typical of Madison's recent parties is, for the most part, not seen in Chapel Hill, efforts to scale back or even cancel the event near UNC's campus are not unheard of.

Large crowd sizes tend to be the biggest concern, according to James Allred, UNC student body president.

"This year we'll see the introduction of mounted police officers, which will be used for crowd control," Allred said. "We think that will be a real improvement."

Other attempts to calm the atmosphere in Chapel Hill have included limiting parking to shuttle lots outside of the downtown area and installing police checkpoints to watch for alcohol or weapons entering the party area.

"You have to turn in any props," Allred said. "Your pirate sword or your pitch fork would have to be turned in, even if it was plastic."

Unlike in Madison, though, the party in Chapel Hill is not typically violent or aggressive.

"We have none of the property damage and looting [and] there is very little confrontation with police," Allred said. "I'm not really sure what to attribute that to."

With Halloween quickly approaching, Officer Phil Smith at the Town of Chapel Hill Police Department acknowledged the city's luck with limited violence at the party.

This year?

"Knock on wood," he said.

He said he hopes to secure 400 officers to ensure public safety on the night of the event, but said what seems to be most important is stressing to the officers that they need to be patient.

"We've had these [Halloween parties] for so long," he said. "They know what to expect."

Long-standing holiday party traditions are not limited to Halloween, though, especially in college towns.

At the University of Illinois, students take pride in their celebration of a different holiday — St. Patrick's Day.

For the past 10 years, students donned in green have headed to "campus town," an area near campus that is home to most of the city's bars, to celebrate what has come to be known as "Unofficial."

Because St. Patrick's Day typically lands during students' spring break, one Champaign bar owner took advantage of the opportunity to invent a party for students to celebrate the holiday while they were still in town.

Bars open their doors at noon for the occasion, filling to capacity almost immediately.

And while the party at campus town has not been as violent as Madison's Halloween party, it is not without its own challenges.

"The biggest concern is that it happens during a school day," said Jeff Christensen, assistant chief of police at the U of I police department. "We have a problem in larger lecture halls with intoxicated individuals."

Students skipping class is not uncommon, and the university has even taken steps to try to persuade professors to schedule midterms for the Friday of the party so students would be deterred from skipping.

"Both the city and the university have worked for years to try to mitigate or lessen the effects of [the party]," Christensen said, adding there have been attempts to turn the bill over to the bars who invented the party.

But the festivities at U of I, UNC and UW seem to have staying power in their respective cities.

As Allred put it: "It just seems to be an important part of student life."

This year

Madison's Halloween celebration has seen significant changes since its birth, and this year's event is slated to include a venue different from any seen before.

Installation of boundaries aimed at containing the crowds on State Street along with a $5 admission mark the biggest changes, as city officials look to curb the aggressive nature of the event.

"One of our measures for success will be that we don't need to use pepper spray and police don't need to get into riot gear," Cieslewicz said. "You never want to see that."

The hope this year, he said, is that a more organized structure will be more conducive to crowd control especially at the end of the night.

Joel Plant, Madison's alcohol policy coordinator, said the idea this year is to "create a structure that people are familiar with." People are used to going to stadiums and concert halls with ticket stations and security officers, he said, and this year's atmosphere will have a similar feel.

Verveer, one of the "few and the proud defenders of State Street Halloween," is also optimistic about the new plan, but added the event's bad reputation in recent years often overshadows the highlights of the city-hosted event.

"People always hear about how much Halloween costs the city," he said. "But they have no idea that a big chunk of that is covered by [Halloween-related] fines."

According to Verveer, roughly $350,000 was raised last year from Halloween-related fines, most of which resulted from minor law infractions.

With all its controversy and anticipation, Verveer said what it boils down to is keeping the student tradition alive and safe.

"It's a big deal to a lot of students," he said. "The mentality is, we work hard, but we also party hard."