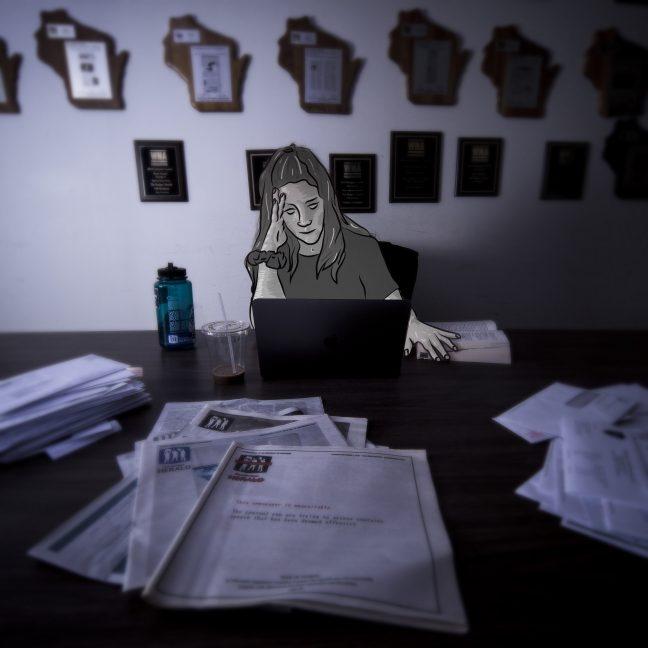

The windows in our office refuse to shut all the way. On a good day, two computers function properly. The lights flicker incessantly and there’s a weird thumping noise coming from the ceiling. I won’t even mention the bills piled high at the end of my desk.

But The Badger Herald puts out a paper every week. A damn good one too, but I guess I’m biased on that.

Walking home from our office, I’m reminded we’re not alone in this rather crowded Madison media market.

The Wisconsin State Journal, The Capital Times, the Isthmus, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel — local outlets competing with big, national names like The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal to deliver their coverage of and their take on the news of the day.

As a journalist charged with telling the stories of those in my community, I know that’s the way it should be. From the audiences served to the writers on staff, every outlet brings something different and — hopefully — something productive to the public forum.

But despite this variety in choice and the incessant stream of newspapers decorating the coffee tables of family living rooms to office waiting rooms across the country, it’s no secret that journalism is facing steep challenges.

Our country has heard the rantings and ravings of a president against the free press. Some have even cheered him on and welcomed the next attack, many times in the form of angry emails or comments on social media platforms to student and professional publications alike.

Abroad, we’ve seen journalists jailed and censored and threatened and even killed for doing their job. We know this because — and I can’t stress this enough — other journalists are telling their stories and reporting these truths and insisting that you should care about it too.

And the worst kept secret in every newsroom is the perilous financial situation so many of us find ourselves in. From paywalls and intrusive advertisements online to cutting back or ceasing print production altogether, newspapers have had to adjust to changing times and changing priorities.

That inevitably includes student publications. An afterthought for many outside the confines of campus, student journalists at institutions big and small are often the only ones reporting on student stories and breaking important news at their university — realities which make the challenges these outlets face all the more tragic and the task of protecting them all the more important.

Panel of journalists talk fake news, responsible reporting in 2018

If not us, then who?

At the University of Wisconsin, student journalism has a rich history. From traditional newspapers to media’s more modern developments, this campus is full of publications old and new, large and small — both online and in print — working to report the news, tell the untold stories and fill the gaps in coverage left by outlets responsible to largely non-student readers.

For thousands in Madison and millions beyond, those gaps aren’t inconsequential. Quantifying the importance of covering college campuses is nearly impossible and qualitatively inadequate, but for UW’s student government, that gap in coverage amounts to about $51 million.

$51 million — that’s how much money the Associated Students of Madison allocates in segregated university fees each year. But for newspapers serving audiences outside of UW’s campus — from local Madison papers, to statewide outlets, to national conglomerates — ASM and its power to allocate that money oftentimes goes unnoticed.

So who, then, is providing that essential check on this student-elected, student-run government? All I can say is that I’ve sent enough reporters to painfully long ASM meetings to know it’s the student press.

Sammy Gibbons, editor-in-chief at The Daily Cardinal, UW’s other student newspaper, echoed that sentiment. She said there’d be a lot of unanswered questions on the “inner-workings of the university” and other issues affecting students if papers like hers weren’t covering campus government and holding the university accountable through their reporting.

“There’s a lot of really important information in things like ASM that people wouldn’t usually care about but is important to know,” Gibbons said. “The student body needs to be informed about their school, and I think there’d be a lot of missing information if we weren’t around to hold them accountable.”

But beyond the allocating powers of UW’s student government, its elected officials are also subject to important reporting which precedent suggests would almost assuredly fall by the wayside if left to larger, explicitly non-student newsrooms.

Campus saw that play out last year, when this paper filed an open records request with ASM and subsequently broke a story about homophobic and anti-Semitic comments coming from members of the Student Judiciary.

As a former representative on the Student Services Finance Committee, the main allocating body of ASM, Jordan Madden said the role of the student press, first and foremost, is to provide “accountability” for UW’s expansive student government.

During Madden’s time on ASM, he said expanding access to affordable health care was one of his top priorities. For him, that included contraceptives. And, most importantly, that included using campus media to bring greater attention and discussion to what he believed was a worthy cause.

After Madden discussed with officials from University Health Services the possibility of offering subsidized emergency contraceptives in campus vending machines, this paper broke that story in large part because Madden said he trusted student newspapers would be the only publications interested in taking on such a story.

It was only weeks later that UHS said they were “happy” to discuss the proposal publicly with campus leaders, culminating in SSFC voting to approve a resolution recommending UW Chancellor Rebecca Blank make emergency contraceptives more accessible and affordable at the university.

From breaking the story to putting forth a cemented policy proposal, Madden said the campus press was integral in working with ASM to drive discussion on campus and push the university to come to the table.

“ASM and student journalists really work hand-in-hand to be productive on issues that really matter on campus, and without student journalism at UW-Madison I think a lot of the progress that we’ve seen on campus in the past couple of years may not have been there,” Madden said.

But ultimately the role of the student press in holding institutions to account expands beyond ASM and student organizations. A behemoth of an institution, UW operates on a $3 billion yearly budget, claims more than 20,000 faculty and staff and ranks sixth in the nation for annual research expenditures.

Staring it down and attempting to keep it accountable is the press — most often and most comprehensively, the student press.

While larger outlets in Madison used to appoint reporters to focus on UW-related and higher education news specifically, many have fallen on hard times and have had to shed those reporters, leaving campus publications as some of the only ones devoted to covering the institution in its entirety and from every angle.

Meredith McGlone, UW’s director of news and media relations and herself a former journalist at The Virginian-Pilot, said she welcomes the role of the student media in holding the university accountable and in providing a voice for the student community on campus.

But beyond the watchdog role that the campus press undoubtedly fulfills for the university administration, McGlone said she finds deeper value in the role of the student press in cultivating a comprehensive view of campus and in making the community they serve a better place.

“As a journalist, I made the occasional mistake and wasn’t always perfect in what I did — but I think on the whole, I and the organizations I worked for were really trying to keep our communities informed and make them better places,” McGlone said. “And I think that’s absolutely true of what I see student journalists trying to do on this campus.”

Charlie Sykes meets with students, faculty to discuss journalism, conservatism

OK, but who’s gonna pay for it?

Integral to fulfilling that role is a sound business model with the promise to see student outlets through to the future.

As it stands, that just isn’t happening. And it’s not only student publications who are facing existential threats to their continued operation.

Jason Joyce, news editor at The Capital Times and former editor-in-chief of The Badger Herald, said the industry as a whole, including his paper, have fallen on hard times and are facing ever-increasing financial challenges.

“The saying used to go, ‘Don’t pick a fight with someone who buys ink by the barrel-load,’” Joyce said. “Where I work, we buy ink by the tanker truck-load. So whatever, that’s a lot of ink and our company has a lot of money. But it doesn’t have as much money as it used to and it isn’t as iron-clad as it used to be.”

For independent student newsrooms, money is even tighter. UW journalism professor Katy Culver, herself a former student journalist, said advertising, oftentimes the main source of income for independent student newsrooms, has changed for student publications and has placed it in direct competition with other local papers and the university itself.

Faced with mounting costs and falling revenues, student papers have struggled to adapt and stay competitive among publications that have the resources and staff to stay cutting-edge and push the ever-growing relationship between journalism and technology forward.

As a result, Culver said student newsrooms appear bound to traditional perceptions of journalism, unable to adapt to an industry that appears to change every day.

“One thing that has always fascinated me about the student newsrooms that I’ve encountered in the 18 years that I’ve been teaching here is that, in this massive digital disruption, 19-year-olds are some of the most tradition-bound people,” Culver said.

But not every student newsroom faces this problem. For many, money is assured every year. But, as with all things, it comes at a steep price — institutional ties to the university they serve.

But at what cost?

At UW, both of our student newsrooms are operationally independent from the university. Unsurprisingly, both are struggling financially as they operate in an environment increasingly hostile to traditional newspapers.

Joyce described independence as the “heart of journalism” and stressed that journalists need to sit outside the institution they’re tasked with holding to account. Even McGlone, who would seem to benefit from UW’s student newsrooms being connected to the university, stressed that she found value in the fact that both of UW’s student papers are responsible to themselves and only themselves.

“People may not like every article that a news organization produces, but I feel really, really strongly that independent news coverage makes communities and makes institutions better,” McGlone said.

For student papers who find themselves attached to the universities they serve, it’s not uncommon to find friction between the university administration and the student press over their editorial decisions.

That’s the setup at UW-Stevens Point, where the student paper, The Pointer, receives most of its funding from the university or from the student government. Erica Baker, The Pointer’s editor-in-chief, said it “would give [The Pointer] a lot more freedom” to be separated from the university “because, in that way, [it] doesn’t have someone almost owning [it].”

Regardless, Baker said she doesn’t let the institutional setup stop her from reporting on important stories and stepping on some toes along the way.

“I know things we have published in the past have upset people in the administration and have upset [student government],” Baker said. “It can be difficult to navigate, but at the same time I think it’s important to report the truth.”

But non-independent papers at other schools, like the Liberty Champion at Liberty University, have faced an administration much more willing to exert their authority over their student newsrooms.

During the 2016 election, Liberty University’s president, Jerry Falwell, an ardent and vocal supporter of President Donald Trump, was reported to have taken an active role in killing stories critical of Trump and in forcing opinion columnists to openly admit who they were voting for in that year’s Presidential election at the end of their pieces.

Tensions over publication and editorial decisions between the university and the paper continued to mount, culminating in the university’s firing of the editor-in-chief and the news editor later that year. Four other staff members resigned shortly thereafter.

Speaking to the new staffers, Bruce Kirk, dean of the Liberty University School of Communication and Digital Content, made clear to them what he saw as the role of the student press on campus.

“Your job is to keep the LU reputation and the image as it is. … Don’t destroy the image of LU. Pretty simple. OK?” Kirk said. “Well you might say, ‘Well, that’s not my job, my job is to do journalism. My job is to be First Amendment. My job is to go out and dig and investigate, and I should do anything I want to do because I’m a journalist.’ So let’s get that notion out of your head. OK?”

While most universities do not take such an active or suffocating role in their student newsrooms, the incidents at Liberty are a painful reminder for many non-independent papers that the university could always assume such a role if they chose.

The Liberty University incident, then, shows that independence is often the only way student journalists can guarantee their ability to investigate uncomfortable stories and publish them in the light of day.

Wisconsin political reporters hand down advice in turbulent times for journalism

Pick your poison

But many student papers have found themselves at a crossroads with no clear compromise or middle ground.

In the face of falling revenues and an increasingly difficult market for student publications, do they bite the metaphorical bullet and welcome the steady resources that come with attachment to their university?

Or do they accept an oftentimes unsustainable financial model and devote themselves to maintaining their operational independence, thereby guaranteeing their right to investigate, write and publish what they wish?

On one hand, while the Liberty Champion undoubtedly had their editorial autonomy suffocated by the university administration, the editor-in-chief of that publication was the recipient of a $3,000 scholarship — which is about $3,000 more than I can say for the editors-in-chief at both of UW’s papers.

But on the other hand, if either of UW’s student papers had tied themselves to the university administration, I can’t say for certain that we would have been able to publish as many stories as we have about viscerally important issues for this community — stories investigating UW’s ties to the KKK and the wider culture of intolerance on this campus both past and present, stories addressing the problem of food insecurity on this campus in light of an unpopular mandated meal plan, stories illuminating the voices of UW’s students of color and providing substance to the anecdotes we’ve all heard about their experiences on this campus. And that’s just to name a few.

In the face of these divergent approaches, one thing is for certain. The need for quality journalism will only intensify in years to come. And for Madison, that’s all the more true.

We live in a city and a campus of contradictions. We’ve heard stories about how supposedly “liberal” this place is, about how it’s “77 square miles surrounded by reality,” about how it’s a beacon of progressivism in a sea of red.

But not to be ignored are the stories of intolerance, the stories of how marginalized students are more likely to feel unwelcome and face harassment or hostile behavior, stories of how a black candidate for public office gets the cops called on her and her 8-year-old daughter for campaigning in the district she calls home.

So how is one to make sense of this — especially the student community, which comprises nearly 50,000 of this city’s population and yet also oftentimes finds the place entirely foreign?

Therein lies the value of journalism — and for students, the value of student journalism.

In this world, we’re all engaged — even those who claim they don’t get involved in politics and “prefer to stay out of that whole thing.” At the heart of this expansive campus, making sense of the community we’re all invested in, is student journalists.

But we’re facing real challenges. And while we struggle, this whole campus loses.

So going forward, an obvious solution to this problem is to support your student journalists. To read their coverage. To include your voice in the collective discussion.

Because there’s just too much at stake to do otherwise.