After converting to Islam in 1991, Faisal Abdu’Allah was given a name that means judge — someone who distinguishes between truth and falsehood.

Living up to the name, a central theme in Abdu’Allah’s works is finding the truth in both one’s self and surroundings.

An associate professor of printmaking at University of Wisconsin, Abdu’Allah recalls some of his first artistic efforts, the nuance and challenges of addressing his experiences and now being a teacher of the arts.

Abdu’Allah began his path towards printmaking and photography after a student-exchange program sent him from the London College of Art to the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in 1989. It was there also that he heard speeches from a local lecturer from a nearby mosque on the radio, which energized him to reconsider his identity.

“I had a Scottish name. When the landowners came to Jamaica — where my parents are from — they came from Scotland,” Abdu’Allah said. “They owned the land and they named my forefathers after them. So why should I give credibility to a family that enslaved my forefathers?”

One of Abdu’Allah’s earliest public pieces was “I Wanna Kill Sam ‘Cause He Ain’t My Motherfucking Uncle,” which was inspired by the Ice Cube song “I Wanna Kill Sam.”

That work was also Abdu’Allah’s first effort that featured his own photography, a suggestion from a professor because it would add more substance and subtract potential copyright issues, he said.

The result was Abdu’Allah taking some pictures of his friends, blowing them up to a larger than life size and then printing them onto steel. Abdu’Allah explains the three-print work featured young men he knew, but for the art world, what stood out was that they were black.

“[The art world] thought, ‘These people are not the common occupants of this space, therefore we must highlight their ethnicity’ … and I began to understand that the art world wasn’t familiar with this kind of representation,” he said.

Abdu’Allah said his work is not about emphasizing race, but rather about telling a story again and from the very beginning. In his case, race is a part of his story — but one shouldn’t confuse it as the whole story.

“If you want to call me a black artist, call Damien Hirst or Jeff Koons a white artist — then you can call me a black artist and I’m happy with that label,” Abdu’Allah said. “But if you’re saying that I’m a black artist and that Jeff Koons is an artist, you’re saying that my issues are only black, they’re only about blackness. And I think that it dilutes, it denigrates the intellectual content of the work.”

For Abdu’Allah, it’s important for the art world to understand he works with what he collides most with. Race is a component of his work, but it doesn’t define it.

Instead, he is interested in conveying other abstract concepts in his art, particularly religion. Influenced by the religiosity of his father, a church minister, Abdu’Allah uses familiar religious titles in his work, such as “Garden of Eden,” “Last Supper” and “Revelations.” Abdu’Allah wants people to rethink a realm they thought they knew.

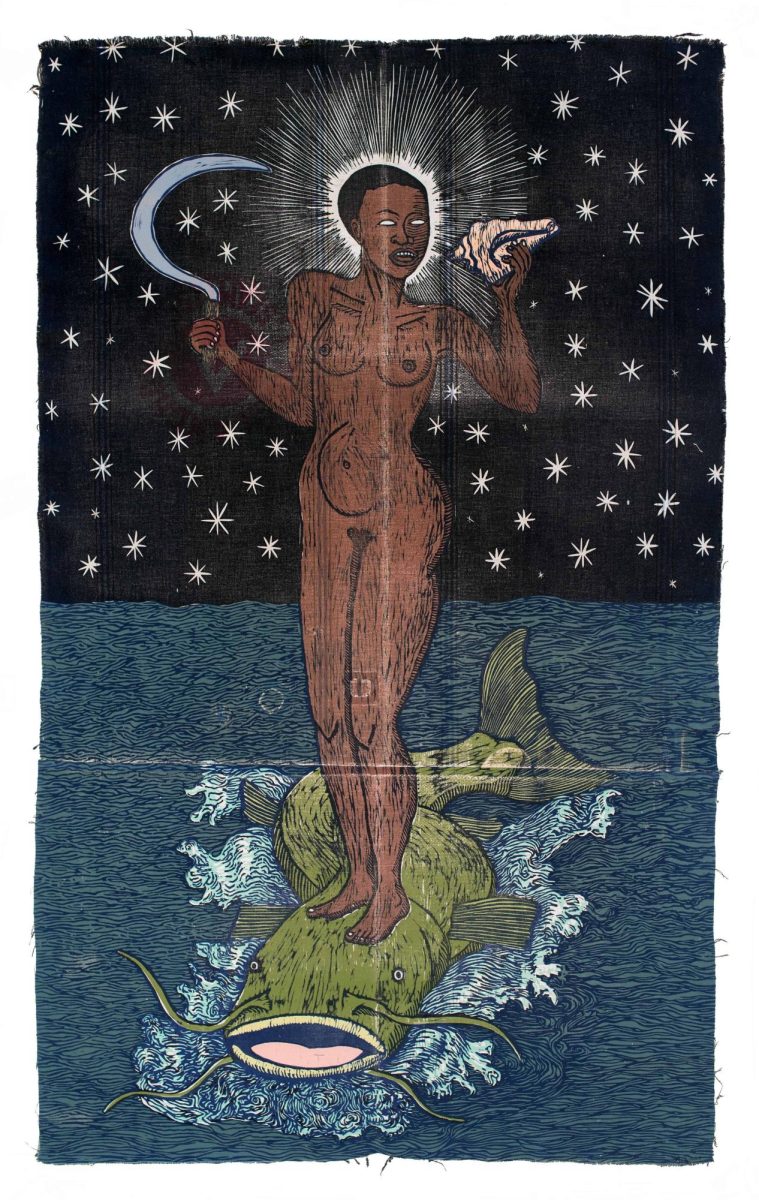

Photo Courtesy of Chazen Museum

“[Working with religious titles] was just opening the first chapter for my audience to try engage with the work,” he said.

As a professor, teaching and conceptions about teaching also plays a large role in his artistic process.

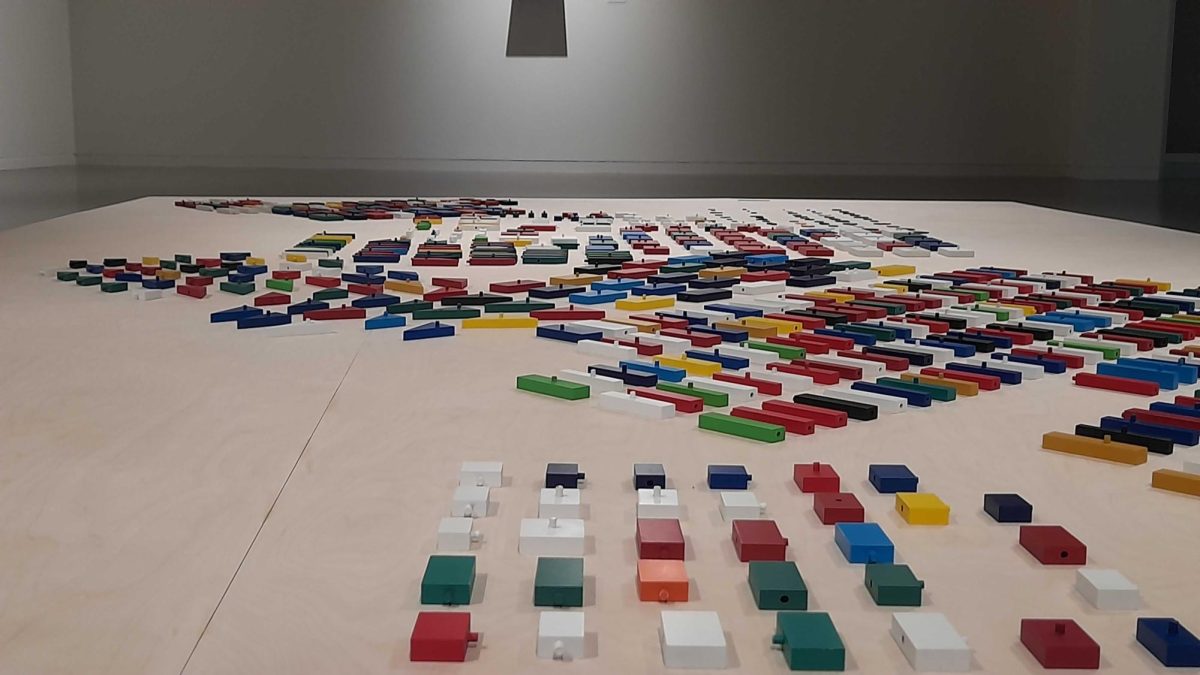

In his recent piece,“The Count,” which is featured in the UW Art Department Faculty Quadrennial Exhibition, Abdu’Allah used a chalkboard with permanent screen print to challenge the audience to reassess the way they were taught, and to re-evaluate what he calls “mis-knowledge,” or purported truths.

“The chalkboard is a space, a conduit that we are taught is the truth,” he said. “The person who is the gatekeeper of the board — your teacher — has certain kinds of knowledge and mis-knowledge that they can continue to support.”

In Abdu’Allah’s own teaching, the most important aspect is having a student walk out of his classroom as somebody different than who originally entered. Abdu’Allah recounted when earlier this year, one of his students “piped up” against censorships and what the word meant to her. He said he had never seen her speak up like that in the two years he had her as a student.

“I know that she is a completely different person now, and I’ve done my job,” Abdu’Allah said.