“Changing Hands: Art Without Reservation 3,” an exhibition of Native American contemporary art open at the Chazen Museum of Art, presents viewers with a huge swath of Native American cultural traditions while exploring their contemporary creativity and innovation. The exhibit’s artists, all from the United States and Canada, utilize a variety of art forms, ranging from wood, beadwork, basketry, textiles, metalwork and stone carving. In addition to these more traditional arts, these artists also engage with modern technology, such as photography, video and performance.

The exhibition starts with the utilization of traditional techniques on modern themes. The most well-done and representative works utilize traditional methods of exquisite beadwork, a technique that uses glass and plastic seed beads and cotton thread to compose beautiful and meaningful patterns. By fusing this art with iPods and iPhones, the artists capture the nature of modern technology using their own culture.

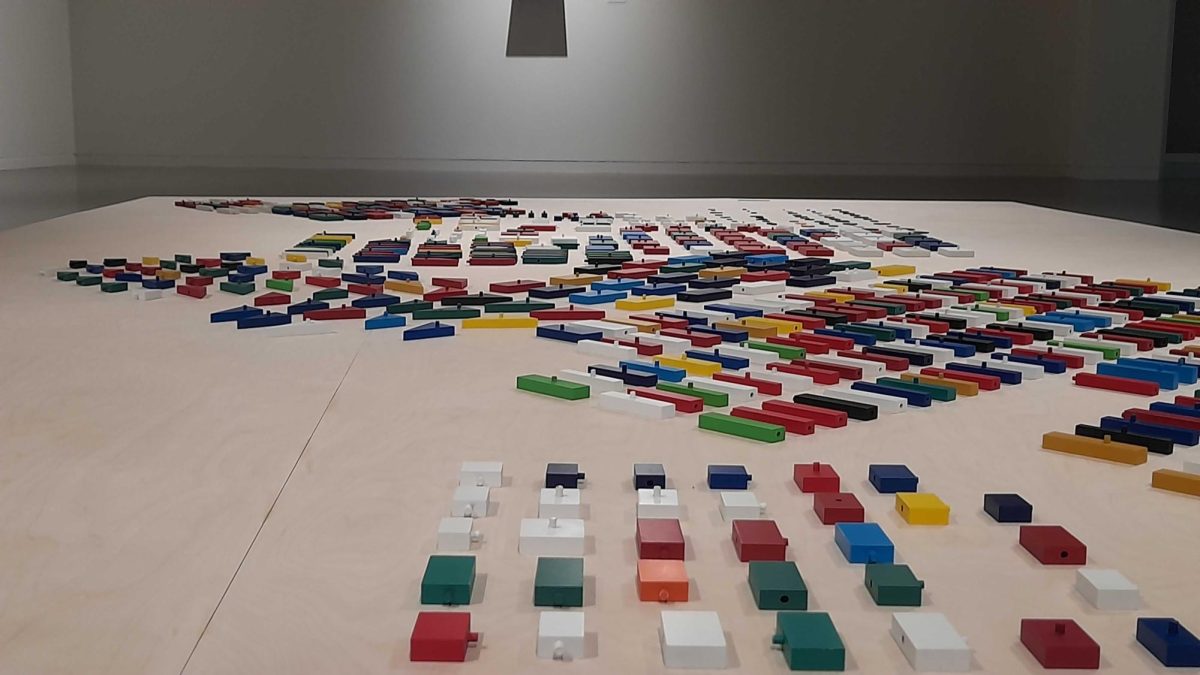

Entering the main room, I was immediately stunned by a net-like object called “Cell,” made by Frank Shebageget. It’s made out of dozens of white nylon square nets, the ends of which are fixed in a square aluminum frame hanging from the ceiling. Each of these nets is transparent, and one could see clearly through it if there was only one of them. However, when they are placed tier upon tier, so closely and neatly, it becomes a hazy cube that looks like a pure cloud.

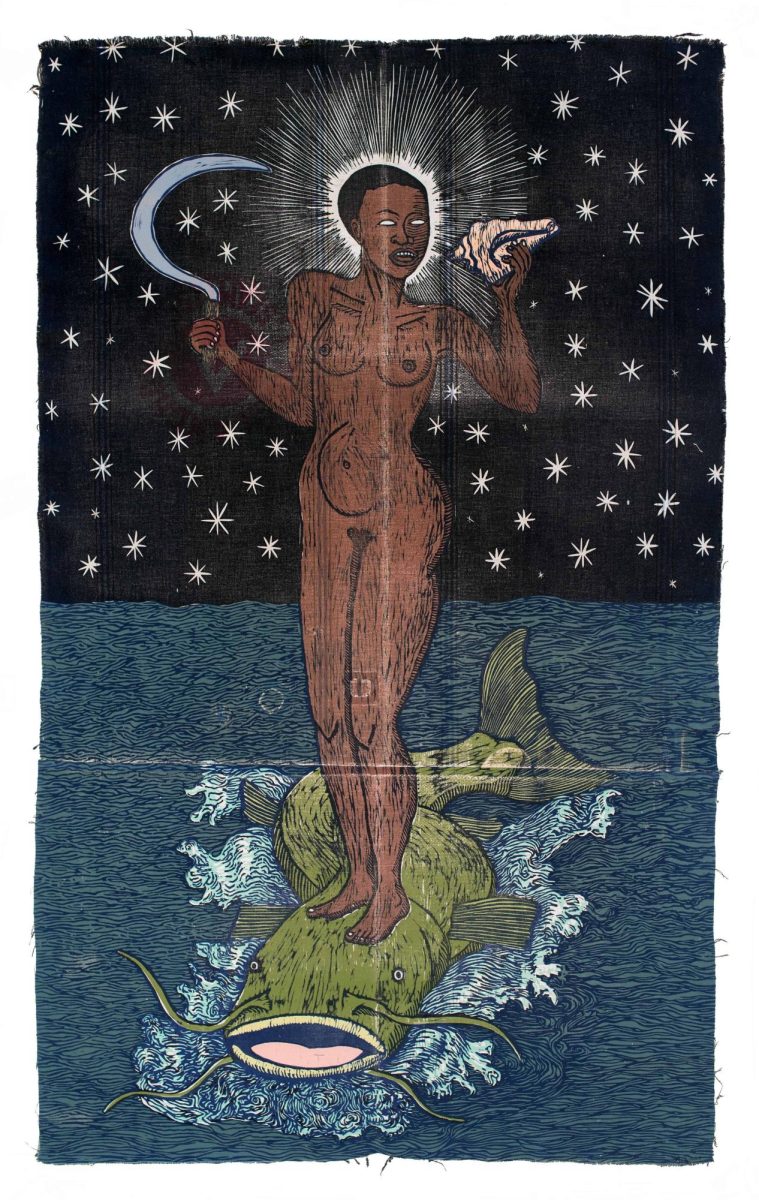

Much of the artwork in “Changing Hands” questions the myths and stereotypes about indigenous people and their culture. The painting that did this best, Kent Monkman’s “Kiss the Sky,” gave me the deepest impression. The painting brings to life a scene in a canyon with a background of grand mountains and flowing clouds. In the scene is a Native American, wearing a huge Indian headdress made of pink feathers and a pair of pink high-heeled mules, with his left arm reaching toward the sky, collecting falling feathers, and his right hand holding a feather. In the sky, there are two white men with wings, their bodies twisting together, indicating an intimate relationship between them. The Native American’s gender is unclear: he looks masculine but wears a feminine outfit, and a long, pink strip of cloth covers his lower body. The painting reminded me of the “berdache” people in Indian culture, whose bodies manifested both masculine and feminine spirits. These people were special but important because they held specific roles, such as healers, foretellers, matchmakers. The painting raised more questions than it gave answers. Is Monkman attempting to challenge the diverse but repressed sexuality during the colonial period? Does he want to clarify the real meaning granted to “berdache” people? Does he try to use this painting to inspire people who were marginalized by social norms to speak out and gain the power for their community today? Does he try to unite white people and indigenous people to fight together for the same goal? Works like this one kept me on my toes, illustrating a provocative reality but a promising future.

Changing Hands: Art Without Reservation 3 is open at the Chazen Museum of Art from Feb. 7 to April 27.