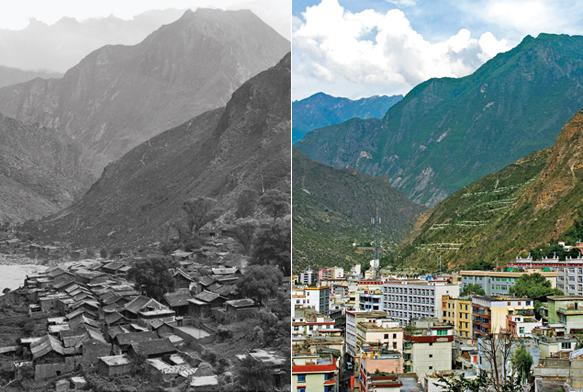

In a new campus exhibit, the past is meeting the present in “Evolving Landscapes: 100 Years of Change in Western China,” a re-photography exhibit running throughout November.

The show pairs images of Western China taken by Ernest Henry Wilson, an early 20th-century British explorer and photographer, with modern images by Professor Yin Kaipu of the Chengdu Institute of Biology. Kaipu re-photographed Wilson’s work, capturing the exact locations 100 years later.

The exhibit is part art project, part social study, part observation on how time touches the world. It showcases the social, cultural and economic changes in Western China and the way they have touched the environment. It does not pass judgment, however. It marks the passing of landmarks, of trees, of families and disasters and beliefs. It documents the comings and goings of all of these things.

The visual aspect of the exhibit is powerful. The old photos have a hint of mystery in the washed-out neutral pigments that create something beyond exotic to — in my case — modern American eyes. Some images come across as purely historical, but a few are almost otherworldly. The sweeping mountains drenched in fog are jarring and go beyond a simple shift back in time and place. The modern photographs serve not only as a comparison, but as a way of centering the viewer. The photos from Kaipu’s lens allow the viewer to see that these are real places and that real changes have taken place. For better (trees, flourishing civilizations) or worse (ruined bridges, dying plants), the coupled images simply prove that a century is enough to sort through a society’s values.

The gallery is extremely sparse. It is comprised of simple white walls, neutral lighting and monitors showcasing further images from the project. The simplicity is appropriate; the exhibit itself is a study of time, place and context. Any attempts at manipulating these in the presentation would take away from the experience. There are plaques throughout; some note the focus of the changes seen in the photos (cultural, religious and environmental) while others provide brief historical context.

The exhibit’s weakness is in these plaques. While those identifying category are helpful, the informational paragraphs prefacing each image set take away from the experience. The words themselves are fairly dry. There is a nagging feeling that not reading the informational blurb will result in an incomplete experience. When read, however, there is a sense that the viewer is walking through slides for a lecture on the history of Western China rather than a gallery. Although a history lesson has its merits, the gallery is not the time or place. The images beg to be taken in as a purely aesthetic experience and only then applied to the historical context. “Evolving Landscapes” is rich and multi-layered, but it tries to showcase too many layers at one time.

“Evolving Landscapes” is an interesting diversion. It is relevant, well-researched and beautiful. There has been a rise in popularity for re-photography projects in recent years, but while many of these are scrolled through as a curiosity, the images of Western China are more powerful in person. As Bob Dylan sings, “The times, they are a-changin’.” This exhibit is a way to start a conversation on why and how.

“Evolving Landscapes: 100 Years of Change in Western China” runs from Nov. 3 to Nov. 28 in the Ruth Davis Design Gallery at Nancy Nicholas Hall. Gallery hours are Tuesday and Thursday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. and Sunday from 12 p.m. to 5 p.m.