“Inhabited Landscapes,” a series of artworks on display at the James Watrous Gallery of the Overture Center until Oct. 27, takes the viewer through a series of diverse experiences. The exhibit is a compilation of contrasting, conflicting styles that characterize the individual outlook of each artist on the Wisconsin landscape.

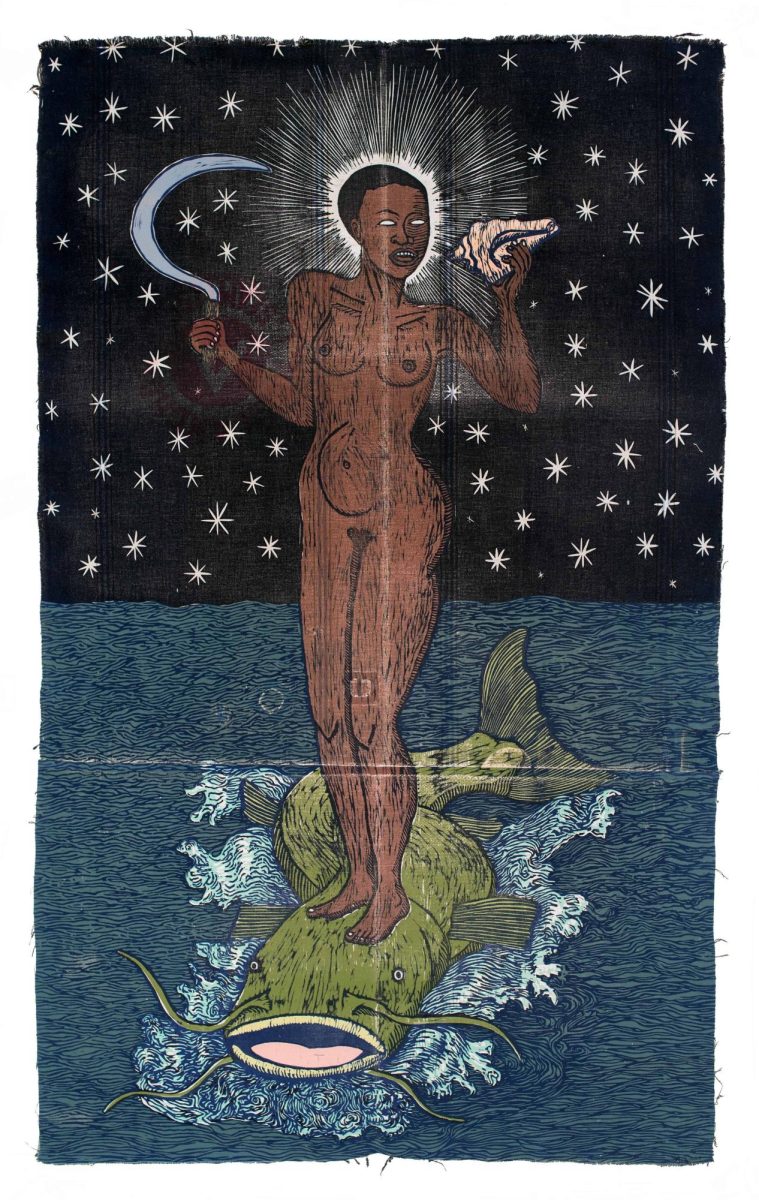

This captivating maze begins with a memorable, bold piece called “Paradise Lost,” a conundrum of a painting that sneaks in a Gauguin-esque figure and a style that immediately recalls Keith Haring with its line-based arrangements and simplistic, flat, yet compositionally magnifying figures.

The aforementioned work, by Charles Munch, is one of the strangest and most abstract of the bunch. What follows is a layering of experiments: artistic commentaries on reflection, light and the simple pleasures of nature. Each of the seven artists has contributed his or her own self-interpretation, a written explanation of how they “inhabit” the landscapes with their own ideas, thoughts and experiences. For instance, Tom Uttech compares his journey to that of “the religious pilgrim seeking a message from God.” His works reveal a fascination with reflection, literally, with ponds occupying the foreground and mirroring the trees of the above landscape. A prevailing theme in his works is the image of an animal staring at the viewer in a “funny-seeing-you-here” manner, as if asking the viewer to further address his or her role within these beautiful scenes of nature.

The main room of the gallery boldly introduces itself with a daring piece by David Lenz, which seems to scoff at convention. The center foreground holds the unsettlingly realistic image of two city kids smiling (for some unknown reason) directly at the viewer, while an incredible show of light dazzles the sky behind them and recreates the subjects as misplaced angels at the center of an abstract scene. The painting asks more questions than it answers, and its compositional flaws serve as an interruption of the actual content.

Dennis Nechvatal has a more modern outlook on landscape. His self-interpretation is a complex enumeration of words and phrases, such as “not of the landscape” and “eden is closed.” These random scraps of thoughts don’t provide much insight into his pieces but attempt to convey some vague idea of depth or awareness. His works focus on the detail of simple scenes: water colliding with stones in a pond, ripples coursing through streams; his pieces are pleasurable as they envision a nature that is ideal, meditative and somewhat predictable. His bold lines and unique portrayal of detail bring the viewer back to Munch, whose pieces are the oddballs of the exhibit. He has an obvious penchant for clouds and uncomfortably placed objects: “Boiling” shows two men playing with a large fire, with a random, elegant table balancing the scene at the left. “After the Storm” reveals a horseback rider passing a large statue of a nude woman, a combination of subjects as befuddling as the figures in Giorgione’s “The Tempest.”

John Miller, Barry Carlsen and Cathy Martin also recreate illuminating worlds, characterized by memories, feelings and even mysteries. Carlsen’s “Faded Blue Orange” builds farmland to frame a tired, seemingly isolated old man, who stares at an unfixed point before him, out of the realm of the viewer. Paintings like these keep the viewer on his or her toes throughout the exhibit, as artists both latch onto and recede from the landscape, illustrating the ambiguous relationship between human thought and the beauty of the natural world.