Art perpetuates an incestuous folding in on itself.

Defining status and style, artists have always managed to compare themselves or be compared to their peers and predecessors alike. For this reason, it is clear to see that the infiltration of early 20th century modernist art, like Cubism, Fauvism and Futurism, lend itself to the adaptation of expressive street art and other forms of graffiti.

Today’s popularization of street art comes with a tip of the hat to the building- and curb-plastered works of Shepard Fairey, and the spray-painted stencils of Banksy. They both independently gained mass acceptance with their work in urban location. With this, the last decade has seen a major shift from the gallery to the urban environment, challenging art critics and rejecting the controlled confines of white-walled galleries and museums.

Not only did the site-specific artists of the ’70s make great strides in deconstructing the expectations of high art, they managed to remain prolific. Is it possible for street artists who do not have formal training to be as substantial with their work, or are these two worlds just involved in some sadistic fatal attraction with each other?

Artist Carlos “Mare 139” Rodriguez is currently dancing this twisted tango. He recently gave a lecture at the Chazen Museum of Art called “Art for the Next Century: How Graffiti Transformed Contemporary Art and Remixed History.”

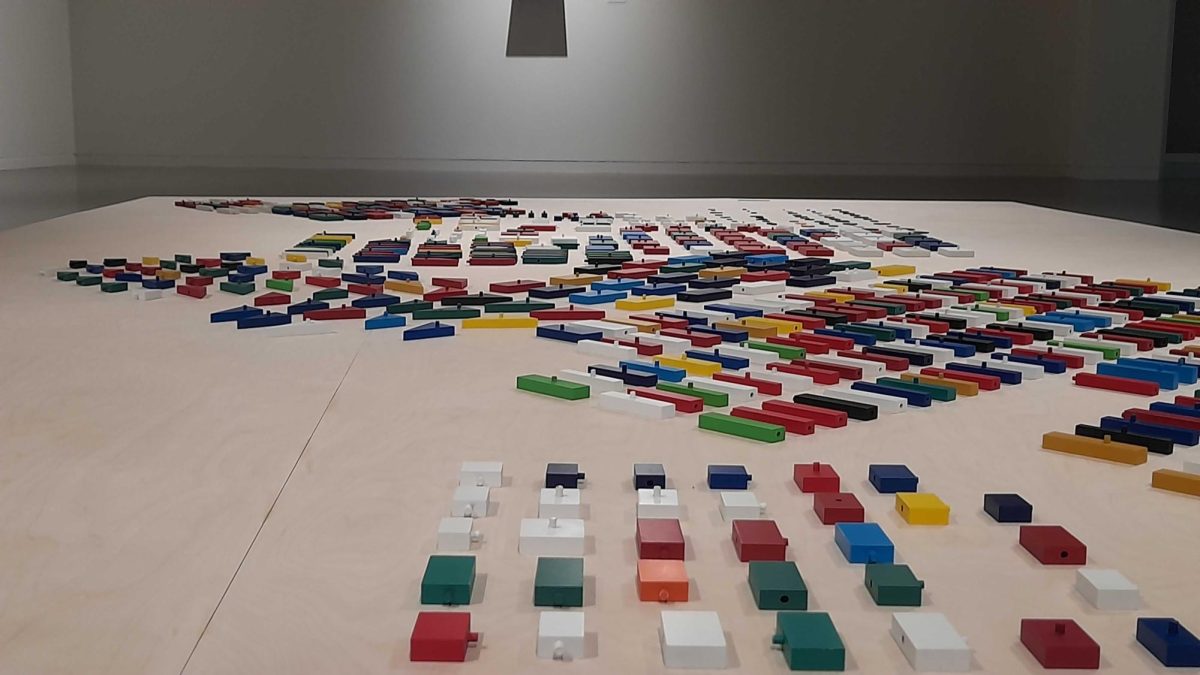

Mare is a joint product of street smarts and artistic expertise. His upbringing submerged him in the hip-hop scene surrounded by other graffiti artists and b-boy dancers of the ’80s. Crossing genres by collaborating with hip-hop dance styles and gestural drawing led to his career as an artist. He is now best-known for producing sculpture, industrial and graphic design.

His work pushes out of urban graffiti as process-oriented forms. During his presentation at the Chazen Museum this week, the former graffiti artist made several references to late 20th century artists and movements.

“Remixing [art and culture is] the new frontier of contemporary art,” he said.

On more than one occasion, he referred his own study in art to be closely examining Frank Stella. Unlike many of his peers in the graffiti underground, Mare studied at Parson’s School of Design in the ’90s.

Mare’s first visit to the University of Wisconsin-Madison was in the late ’90s. At the cutting-edge for that time, he was developing ways to make art via graphic design and he has successfully designed websites with the same stylistic flavor that represented hip-hop culture at the time.

Currently, he creates moderately-sized sculptures from sheet metal that embody an energy inspired by dance movement. The artist’s approach is to enter a gallery space and produce work on the spot. This can be directly contributed to the method in which graffiti art occurs. The the difference is that Mare’s work is commissioned rather than illegal.

Mare ended his presentation with a quote of his own; “Pioneers are the first to see it and the last to be seen.”