The Badger Herald had the opportunity to chat with Sudanese writer, Leila Aboulela, and get some special insight on her latest book, “River Spirit.” Readers have the opportunity to learn more about Aboulela in-person Oct. 20 at Madison Public Library for the Wisconsin Book Festival’s Fall Celebration.

Aboulela has received prominent praise for her writing that focuses on the interior lives of Muslim women and themes of identity, migration and Islamic spirituality. She has published several novels including “River Spirit,” “Bird Summons,” “Minaret” and “The Translator,” a New York Times 100 Notable Book of the Year.

Aboulela has been long-listed three times for the Orange Prize — now known as the Women’s Prize for Fiction — and her work has been translated into fifteen languages, demonstrating the global reach of her work.

Macklemore to perform in Milwaukee as part of ‘Ben’ tour

Could you tell us about yourself?

I grew up in Sudan, in the capital Khartoum. I loved reading fiction, but I didn’t think that I would ever be a writer.

I went to London to study for a postgraduate degree in statistics but then I failed in getting my PhD. At the same time, I found myself living in Scotland. My husband found a job there and I had two little children. I was reassessing my life and realizing that Sudan was going through difficult times. There was a coup and I wasn’t gonna go back or do statistics because I wasn’t as good at it as I thought I was.

I started to go to the library and read novels then I started to write. I wanted to express feelings and explore the confusion in my mind about leaving home and having not really said a proper goodbye. I started to attend creative writing workshops and everybody was very encouraging. I started to send out stories to magazines here in Scotland and things took off from there.

Could you provide an overview of your book and your inspirations for writing it?

My biggest life event was moving from Sudan to Scotland with two children at the age of 26. Most of the novels I write are about women away from home. That became the subject that fascinated me and I got very interested in the work of Jean Rhys, who wrote about women drifting in Europe on their own. She’s most famous for “Wide Sargasso Sea.” She wrote the whole novel from the point of view of “The ‘Mad Woman’ in the Attic” from “Jane Eyre.”

She picked up a character from a classic and told us about this character — how she was a woman of color, how she came from the West Indies islands, and how she was exploited. Everybody who reads “Jane Eyre” sees her as an impediment in the plot, but then Jean Rhys makes her into the heroine of her novel.

Touch of Ukraine serving traditional dishes on Madison’s East Side

How did your main characters in “River Spirit” come to life?

We start off with an 11-year-old Akuany. She’s orphaned in a village raid in South Sudan, so she and her brother are rescued by this young man working with her father. Akuany develops a crush on him, but to him she’s just a child.

The story follows her life, how she becomes enslaved by the governor’s wife and separated from her brother. The young man tries to get her back and he can’t because he doesn’t have enough money.

The novel follows this fictional plot while at the same time, there’s a lot of Sudan’s history that’s accurate. There is a man who claims to be the Messiah, and people believe him because the population is struggling. They follow him and he manages to unite all the tribes of Sudan against the government in the capital.

The novel tells this history through the point of view of the young girl, but also through many different characters.

It’s the kind of history that has always been told from a colonizer’s point of view, a British point of view. I wanted the Sudanese to be the main characters and for them to tell the story.

Are there any themes that you want students to take away from your book?

It’s to understand perspective and how a story could be told from Indigenous people’s point of view. It will be different from the story that the colonizer will tell.

When we listen to the voices in the archives, we can hear the voices of those who have been marginalized by history.

Mainstream history is very Eurocentric, written from a white, Christian perspective and a colonizer’s perspective. If there [are] gaps in the narrative, then there’s room for the fiction writer to creatively imagine these voices based on the research as well.

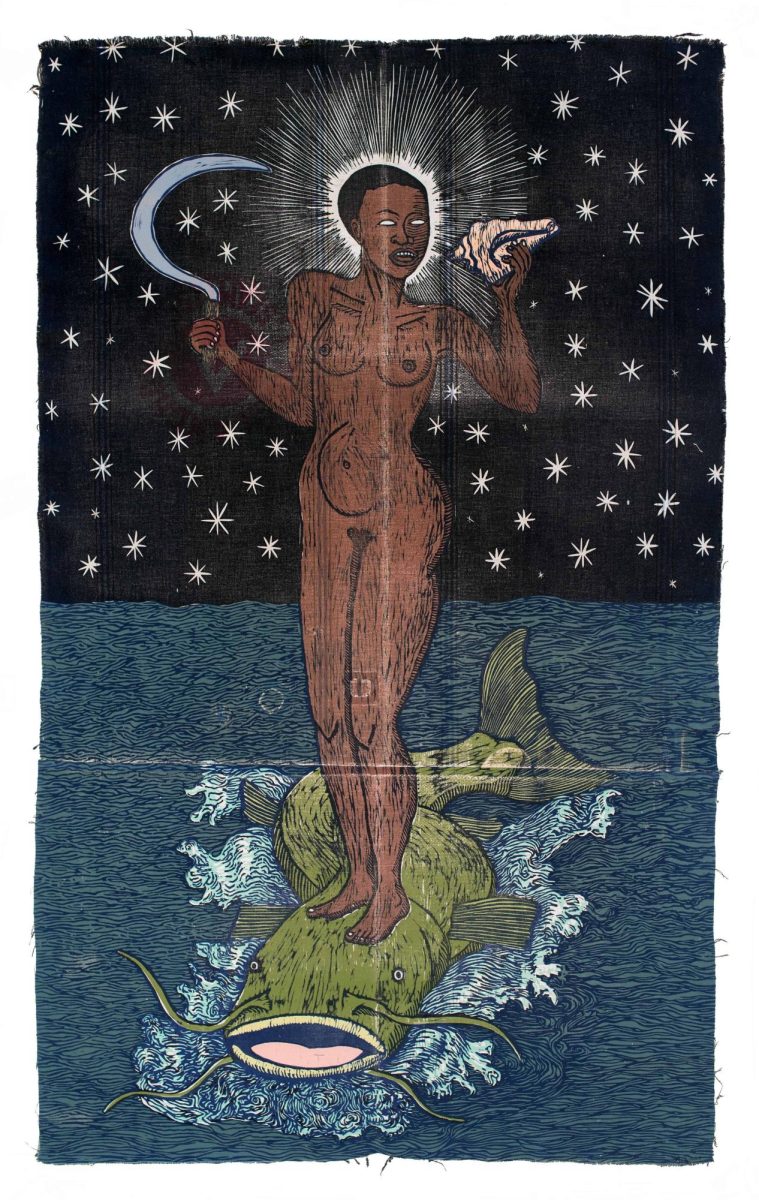

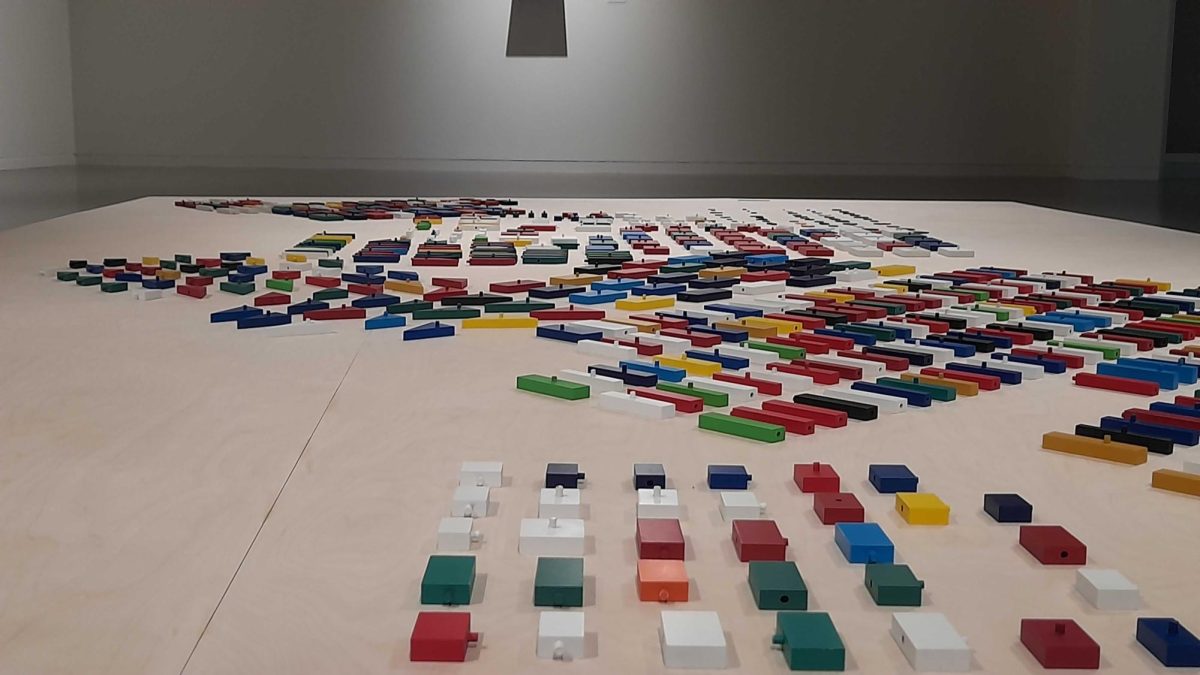

Contemporary African artists examine human condition in Chazen exhibit

Were there any obstacles that you encountered in the process?

The writing was a joy. The obstacle is getting it out to people who are not used to this kind of novel. For example, the same period in history was covered by a Hollywood film in the 1960s called Khartoum. The figure of the Messiah who was Sudanese was played by Laurence Olivier in blackface.

This film got a huge budget. They couldn’t even be bothered to film it in Sudan. It’s all told from the perspective of the white man who’s the hero. My novel, on the other hand, is unlikely to get that kind of attention.

I want this history to be written from the point of view of women and the actual Sudanese, who lived these years. This was their country and this was their lives. That’s my little voice coming up against that big sense of tradition, I suppose.