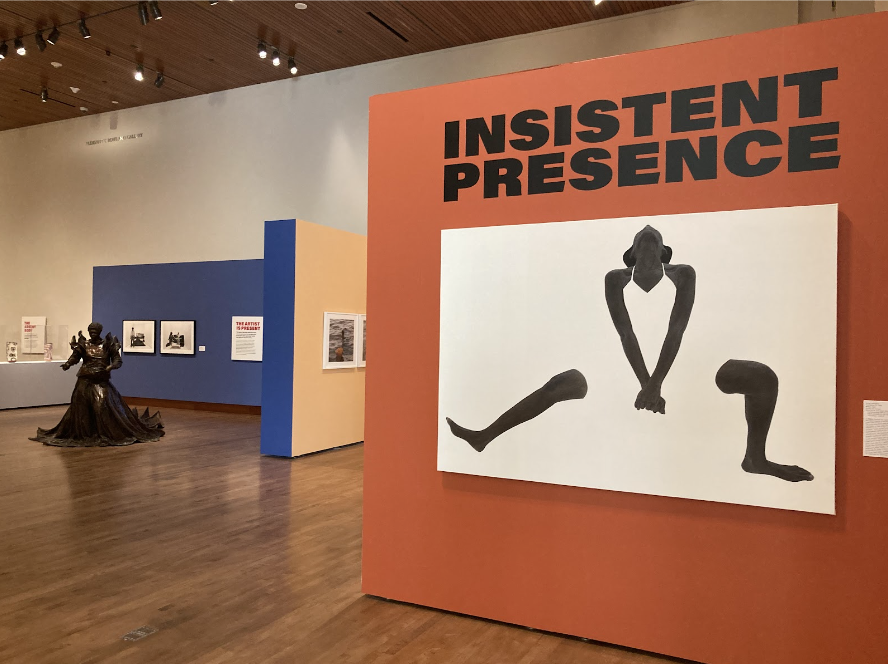

Chazen Museum of Art exhibit “Insistent Presence: Contemporary African Art from the Chazen Collection,” examines the human condition through three fundamental lenses — the body in society, the absence of the body and the presence of the artist, according to the exhibit’s website.

All of 45 of the exhibit’s works were created by contemporary artists living or working in Africa and in the diaspora, according to the website.

“The Body in Society”

In the first section, “The Body in Society,” the artists reflect on how one’s body, or rather identity, is shaped by our experiences and environment. In “Mutual Identity 39,” Dawit Abebe has drawn a figure facing away from the viewer. The grayscale body is in contrast to newspaper clippings which depict various world leaders. In the background, more grayscale figures are shown holding up heavy looking dark cubes, seemingly holding up society itself. The work itself, even the title, evokes our shared history and the struggle that we as humans endured to reach where we are today.

Hamel Music Center features pianist Artina McCain this September

In the sculpture “Bluer on the other side (The problem with immigration),” Péju Alatise has suspended three oars and perched many small figures on a blue painted cloth on each oar. They are small, compared to the oar, and their varied placement suggests that the oars are in motion. The work reflects on the often dangerous and exhausting paths that migrants take in order to reach the promise of more opportunity.

Both of these works prompt the viewer to ask questions about the history of humanity and the often forgotten behind-the-scenes events which have brought us to where we are today.

“The Artist is Present”

In the second section, “The Artist is Present,” the works prominently feature their creators, a vessel through which the viewer is invited to see the artists’ own life story.

In one series of photographs titled “Reconstruction of a Family,” Lebohang Kganye poses as her own grandfather and introduces the viewer to her family’s move into the city. The photos are then put into a stop-motion montage which examines the family’s interactions and creates a unique dialogue between past and present generations.

In contrast, the photographs by Nana Yaw Oduro do not feature his physical body, but rather use his friends and family to portray his view of the world. In his piece “ALL THESE THINGS MY FATHER DOES, I’M CONVINCED HE DOES TO CONTROL ME,” the artist reflects on his relationship by portraying two figures mimicking each other, one representing himself and the other his father. Through this dynamic, Oduro suggests to the viewer that values are passed on, whether intentionally or subconsciously from parent to child.

Both of these artists create a link to explore family history by putting themselves, literally and figuratively, in their family’s shoes, and they invite the viewer on this journey of self-reflection along with them.

“The Absent Body”

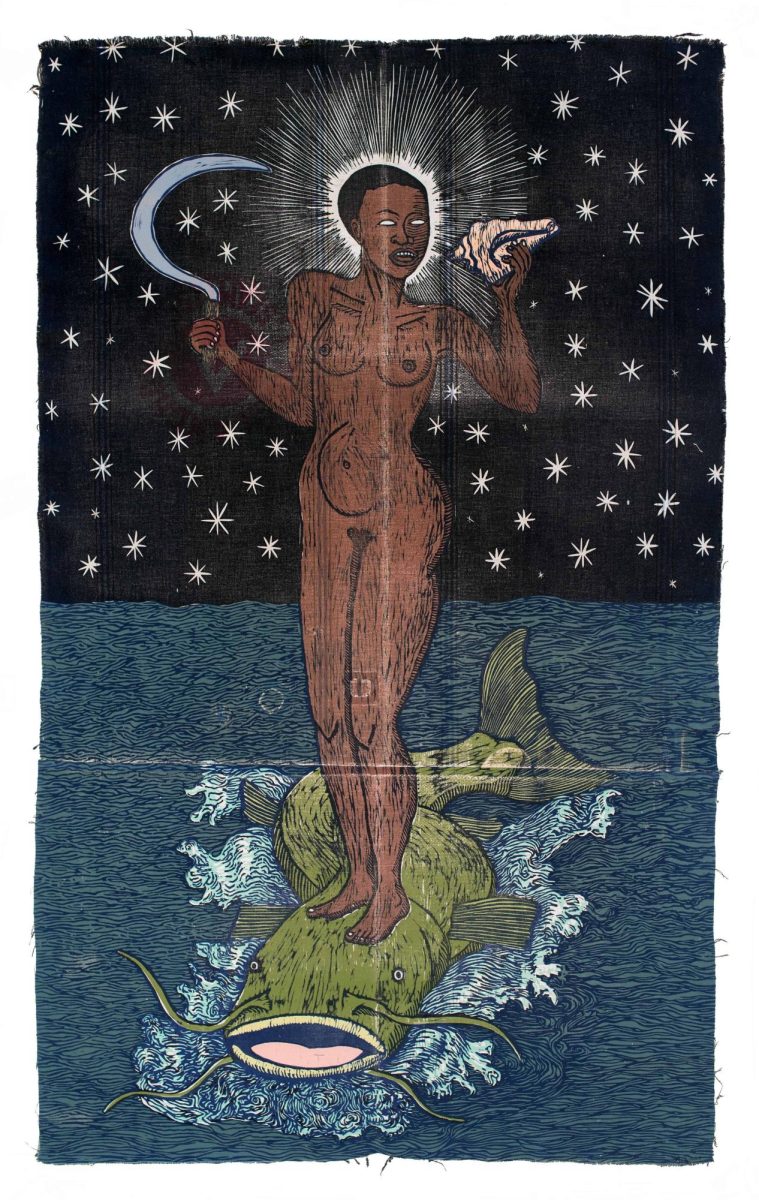

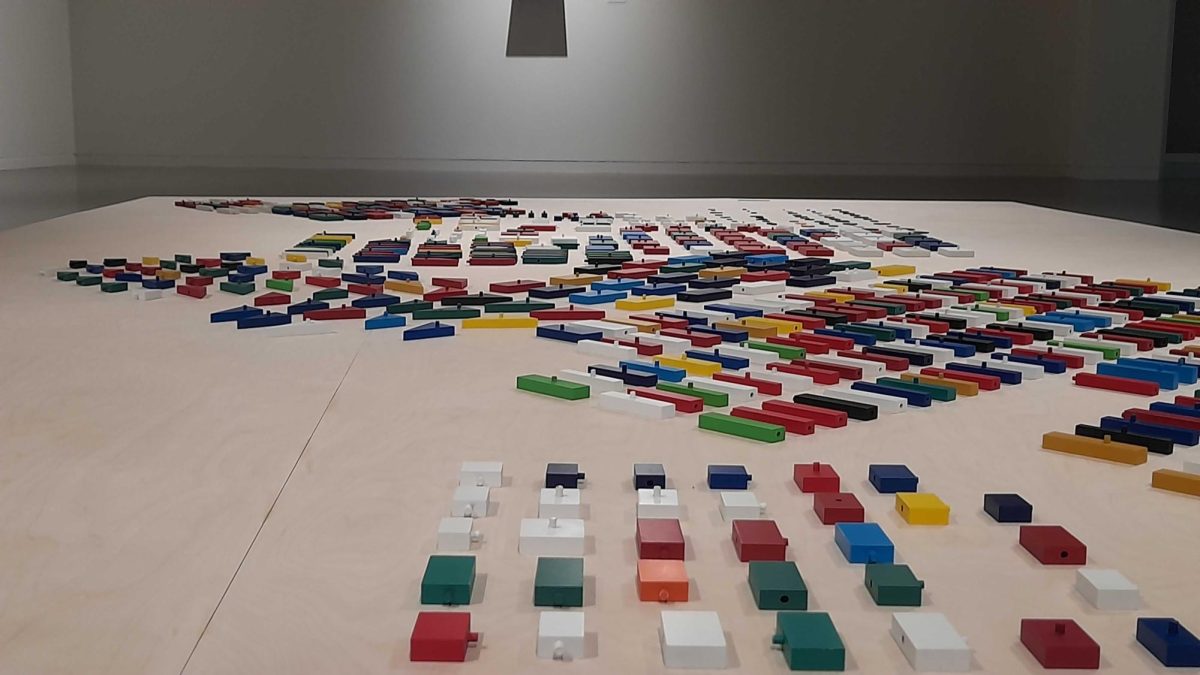

In the final section of the exhibit, “The Absent Body,” artists use other vessels which act as the body. These works use the creation of such unique vessels to explore deeper themes and apply a greater meaning to the overall picture.

Cinemadison to bring critically acclaimed short film back to campus

For example, in “Osaan,” a sculpture by Ranti Bam, the artist treats clay like fabric, molding it and painting it into a beautiful vessel. The clay looks almost like fabric, and it is joined by two patches, evoking a piece of clothing. The malleability of the clay implies healing, and Bam says in the description of the piece that her works prompt her to be gentle with others in life.

Another work, “Virtually mine” by Immy Mali depicts a more recognizable human shape even though the entire piece is made up of small glass squares hanging from the ceiling. Each glass square holds a screenshot of a text conversation the artist had with her fiancé while the latter was working abroad, having access only to digital communication. Each conversation excerpt conveys the yearning that the artist feels and how fragmented we can become in the search for someone else, or even ourselves. The result is our ideal, in this case represented by the overall form of the piece when viewed from afar, as imposing as it is fragile.

In “The Throne of Languages,” Gonçalo Mabunda also gives an inanimate object human characteristics. The throne itself is welded together from inactive warheads, bullet casings and AK-47 magazines, all of which reflect on power and how it is held. The piece is a commentary on the three decades of fighting that plagued the nation during Mozambique’s liberation and civil war. The throne itself is unoccupied, but the eye, mouth and nose-like shapes give it an eerie quality nonetheless, calling back to those whose deaths led to the creation of this work. Through this type of work, artists provoke contemplation on the complexity of the world and the varied ways in which we impact society.

The works in this collection truly push the boundaries of understanding of human bodies, invoking thought and reflection from the viewers. There is something in the gallery for everyone, regardless of background. The pieces invite reflection from the viewer, prompting the question: what is a body, really?

“Insistent Presence: Contemporary African Art from the Chazen Collection” will be available to view at the Chazen until Dec. 23.