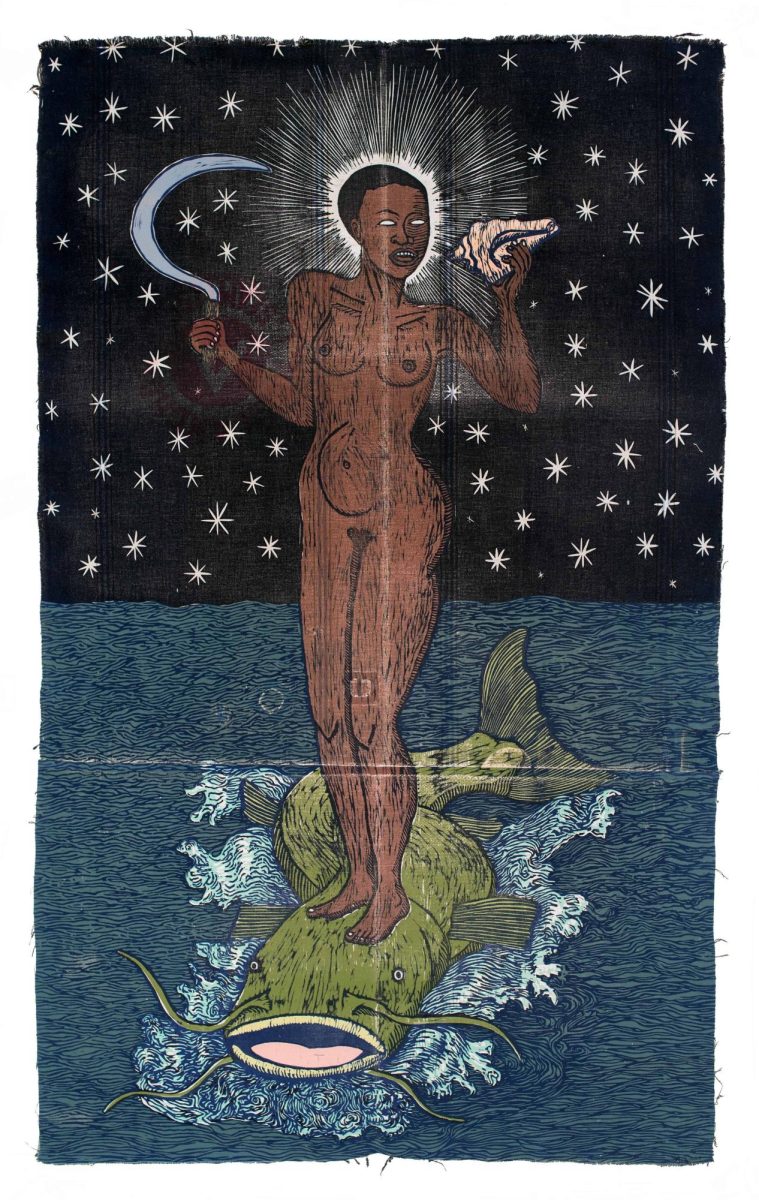

“History is written by the victors,” according to Winston Churchill. Churchill’s quote underscores the human element of bias woven into the retelling of history through text or its representation through art. The Loaded Image: Printmaking as Persuasion exhibition curated in theOscar F. and Louise Greiner Mayer Gallery at the Chazen explores how artists’ beliefs and perceptions impact their depiction of history.

The gallery flows roughly chronologically and features prints in a range of sizes. The largest print, “Hydrogen Man” by Leonard Baskin, will immediately draw viewers’ attention. It looms life-size and features an adult male’s veins overlain on a brown background.

Its raw representation and its anatomical distortion of human biology may jar and unsettle the viewer, as Baskin intended. According to the placard alongside the print, the piece symbolizes the fear of nuclear war pervasive during the 1950s.

The exhibition expertly portrays social discontent as well as popular fear. Unlike much art created during the Renaissance at the behest of wealthy families, the comparatively less expensive art of printmaking allowed artists to appeal to popular sentiment.

Honor? Daumier captures social turmoil and class stratification simply and beautifully in black and white with his “Repos de la France.” In the print, a member of the upper class sprawls on a throne in the foreground while a woman of the lower class sulks in the background, indicative of her social status.

The most evocative prints in the show depict historical events and sentiment simply. Few prints make use of color, allowing viewers to focus on the content. William Weege’s “Hell No I Won’t Go” features just two components: a child and a machine gun. The child’s innocence juxtaposed with an instrument of violence heightens the show’s emotional impact.

Repetition of common themes may also intrigue viewers. Differing depictions of the biblical character the prodigal son demonstrate the use of artistic license to represent history.

One print depicts the story traditionally. By comparison, Thomas Hart Benton’s interpretation shows the son returning to a crumbling shack during the Dust Bowl, allowing him to implicitly comment on the economic climate of the United States through the lens of a familiar story.

The exhibition lacks a homogeneous viewpoint, enabling visitors of different political leanings to connect with the art. Louis Lozowick’s “Crane” and Harry Sternber’s “Enough” differ drastically in their representations of industrialization.

The backlight in “Crane” creates contrast with the machine affording it a grand air. Comparatively in “Enough,” a man struggles to break his rope bonds, presumably symbolizing industrialization, while a factory burns in the background.

Printmaking never seemed so crucial to historical understanding as it does in The Loaded Image. The show allows visitors to visually explore a range of topics from war to poverty, providing a provocative gateway into the academic year.

The Loaded Image: Printmaking as Persuasion is available to view from June 18-Oct. 30 in the Oscar F. and Louise Greiner Mayer Gallery at the Chazen Museum of Art.