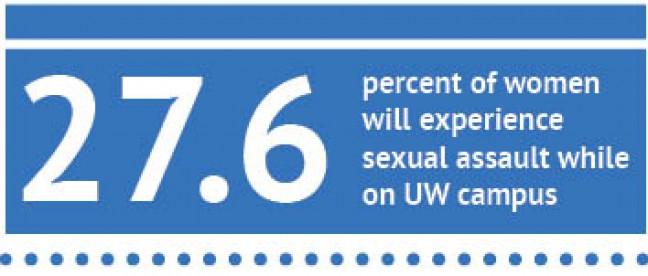

“Please read: Sexual Assault Survey Results.”

Recently, these words found their way into your Wiscmail’s subject bar. Whether you read it yourself or heard from a friend, the contents of this email are now known campus-wide. The highlight of the message is the lasting numerical statistic, a four character summary of sexual assault at the University of Wisconsin: 27.6 percent.

This number is representative of the percentage of female undergraduates who, during the 2014-15 school year, indicated via the Association of American Universities Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct that they had experienced sexual assault since arriving on campus.

The statistic could be the reason you go about your day in distress, mulling over a figure so obscene and dangerous. It might be that you’ve known this since your freshman orientation; nearly every student in America has heard the infamous “one in four” statistic by the time they begin college.

Maybe you spend the day thinking of your best friend, your sister or even yourself. Or maybe you already heard about this from the Tonight Program and now it’s old news; maybe statistics like these just don’t mean much to you anymore and you just … go about your day.

Our constant awareness of sexual assault comes with a lofty price. While colleges nationwide work daily to raise awareness of this issue, an unavoidable consequence of this campaign has become gradual, but powerful, audience desensitization.

Nearly every day, figures like 27.6 percent float around campus inboxes all over the country, not to mention grandiose headlines littering our Facebook feeds. Reactions to these increasingly frequent figures are becoming increasingly apathetic, as we shake our sad, progressive heads in woe, toss the link a sympathetic like and halfheartedly continue switching between the same five apps until we’ve forgotten.

Interestingly enough, the authors of the AAU survey now tell a slightly different story in the wake of the results: “Estimates such as ‘1 in 5’ or ‘1 in 4’ as a global rate [are] over-simplistic, if not misleading.” Further, “none of the studies which generate estimates for specific [institutes of higher education] are nationally representative.”

Honestly, not a surprising conclusion.

First and foremost, a mere 19.3 percent of students contacted around the country replied, with a slightly above average response rate of around 22 percent at UW.

Any freshman with a basic level of understanding of survey methods and statistics is well aware that a survey hinging on voluntary response will never be free of third variables.

Dean’s office calls for student voice in revisions to sexual assault conduct code

In all likelihood, women who have experienced sexual assault feel the most compelled to respond to such a survey, compared to a student who has not faced similar trauma.

The AAU acknowledges this, saying “estimates may be too high because non-victims may have been less likely to participate.”

Secondly, the survey defines sexual assault as “nonconsensual sexual contact involving [either] sexual penetration [or] sexual touching.” The AAU takes enormous care to never mention the words “rape” or “assault” in any question or answer, which is problematic as it fails to consider the spectrum of severity associated with sexual assault.

Under this term, a traumatic rape and drunken waist grab are categorically equal. In no way does this suggest that level of intoxication, relationship to a perpetrator or duration of nonconsensual behavior undermines a sexual assault — so long as the victim feels violated, assault is assault and any level of unwanted sexual advance is unacceptable.

Rejecting silence: Student survivors take control, speak out on sexual violence

But as the survey’s authors acknowledge, they may have lumped girls who would not label themselves as victims into the same category as those who suffer immense emotional trauma and violence.

Perhaps rendering a response,“So? Whether or not they know it, they’re still a victim.”

Which is valid under many pretenses, but not this one. The reality is that of this precarious 27.6 percent of women, we can assume some were not intending to report an assault — they were confirming misogynistic behavior which is undoubtedly disgusting and disrespectful — being hit on, for example — but not physically threatening as far as assault goes.

Which may prompt a reaction as ignorant as: “Oh, the percentage is actually even lower? Great! So it’s not even as a big a deal as everyone says it was. Damn propaganda. It’s 2015. Women can vote. My mom even owns land. Things are awesome; America is amazing.”

Hold on. Take it back it a notch (or 12).

You’re right, I’m not suggesting 27.6 percent is a completely accurate figure. In fact, I’m suggesting 100 percent is far more pertinent.

While the results of this survey don’t confirm that one in four girls are whisked into a car and violently assaulted at UW, they confirm something potentially more dangerous.

If you found out that just 10 to 15 percent of that 27.6 percent actually referred to assault or rape as you may think of it, would you care less? Would this diminished percentage make it seem as though we have made progress, as though women are safer?

That’s the issue we face. In the world we live in, nothing matters anymore without the support of an impressive statistic — a number bigger than you ever imagined — when really, if rape was occurring at a rate of 4 percent, it would be 4 percent higher than it should be.

University of Wisconsin under federal investigation for handling of sexual assault cases

Rape isn’t a big deal because it’s happening to one in four women. Rape is a big deal because it’s happening.

On the chance you followed the hyperlink in the email to the full report and data tables, you probably found several statistics even more shocking.

At one of the most liberal and progressive schools in the Midwest, one which prides itself on social equality and awareness, 40 percent of students don’t believe that a victim of assault would be supported in the community. One in three women on campus have doubts that UW officials would take their report seriously, in the event they choose to report it.

Even more distressing is only 28 percent of female graduate students believe campus officials would take action to prevent factors that lead to sexual misconduct in the first place, astonishing evidence of how comfortable we have become accepting this behavior as just a part of college life.

And on each of these parameters, men are significantly more optimistic — a revealing indication that male perception seemingly continues to dictate the conditions and repercussions of sexual assault, significantly more so than victim’s experiences.

So we don’t just need to reconsider our sympathetic complacency towards sexual assault. We need to tear it up and start a new page.

One cat-call is one too many, and one assault of any nature is one too many.

Surveys, deans and newspapers shouldn’t feel pressure to churn out these startling figures. Instead, we need to integrate systems of support and education into our institution’s policies — to ensure that next year’s survey doesn’t still indicate that only 67.4 percent of students intervened when they were witness to a sexual assault.

That number should be the highest on the survey, coming in at 100 percent, and that is a number deserving of email recognition.

We will not anticipate sexual assault as though it is a scraped knee. Sexual assault is not a certainty, and sure as hell shouldn’t be a part of life. That isn’t to say we forgo preparation, but it is certainly to say that until we dispose of our complacency and acceptance, each of us remains a silent perpetrator.

Whether or not you believe it is misleading, 27.6 percent may illuminate our shortcomings, but it does not need to set a baseline for the future.

We aren’t aiming to watch this number drop. In fact, we aren’t aiming to watch this number at all.

We’re aiming for our best friends, our sisters, our lab partners and our TA’s to walk home past 10 p.m. without having to clutch their cell phones, to never verbally consent out of fear of being labelled a prude, to never have to stay up at night asking why they drank that, why they wore that, why they smiled like that or why they left their house at all.

And when that becomes the goal, the statistics will change all on their own.

Yusra Murad ([email protected]) is a sophomore majoring in psychology and business.