My trek to class Monday morning provided me ample time to think about the week ahead. It’s a twenty-minute walk from my apartment to my introductory Hebrew class. And yet, as I made my way across campus, all I could think about was the 97-year-old victim of Saturday’s attack on the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh.

While not a Holocaust survivor, it is a bone-chilling twist of fate that Rose Mallinger lived to see the rise and fall of Nazi Germany only to be murdered at the hands of an anti-Semite some 70 years later in the United States. The same can be said of congregant Judah Samet, a Holocaust survivor who only survived the shooting because he was four minutes late to synagogue. This fact alone should be enough to remind us how anti-Semitism has eluded progress in the past — it is a prejudice with many faces in accordance with the multidimensional nature of Jewish identity.

In 1970, my grandfather wrote to a local newspaper in Connecticut after my grandmother caught a man puncturing her car’s tires. When caught in the act, the man said ever so matter-of-factly to my grandmother that “they should have made lampshades out of all of [you],” and that she should “go back to where she came from.”

Paul Nehlen’s anti-Semitism, hate does not belong in Wisconsin public office

As my grandfather noted in his letter, “What a terrible, frightening thing to think that in this supposedly enlightened year of 1970 there are minds such as this among us.”

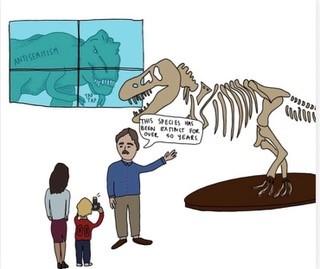

And yet, here we are, in 2018 with 11 Jews murdered at a Synagogue while celebrating Shabbat. This is the boisterous and unabashed brand of anti-Semitism that many deem a relic of the past. What happened on Saturday is without a doubt part of a larger conversation about festering racist and anti-immigrant sentiments asserting themselves in an age of uncertainty. Further yet, it also accentuates the fact anti-Semitism is a distinctly evasive form of prejudice.

Much has been said about the fruitless attempts by Jews in the past to assimilate fully into their European host countries by expunging all ties to the Jewish faith. As my grandfather pointed out nearly fifty years ago, his wife was not “wearing a label saying Jew or Hebe as was the man’s reference” when he perpetrated his hate crime. Precisely because of how complex it is, and not in spite of this fact, grappling with Jewish identity is imperative for young Jews such as myself.

Constant silence on anti-Semitism disgraces social, political activists

I am engrossed in a continual struggle to understand Jewish identity: what it is, why it matters and how I can reconcile it with ostensibly contradictory beliefs, namely my lack of fervent religious belief. An overwhelming amount of modern Jewry dissociates from traditional religious practice, but no matter how far they stray from custom, they will always be defined by those who seek to eradicate them completely. This is a historical truth that proves particularly salient in these times. We should be active owners of our identity — history shows that if we don’t take ownership of our Jewish identity, whatever form that may take, others are more than willing to define it for us.

The massacre at the Tree of Life synagogue should prompt us to remember that while progress can at times seem inevitable, it surely cannot be taken for granted.

Max Bibicoff ([email protected]) is a junior majoring in strategic communications.