In the past year, 48 Wisconsin teens died from fatal car crashes, making car crashes the number one cause of death for teens statewide.

The Department of Transportation marks the third week of October every year as “Teen Driver Safety Week.” Teen drivers make up 6 percent of all licensed drivers, but are responsible for 16 percent of all crashes, according to the DOT.

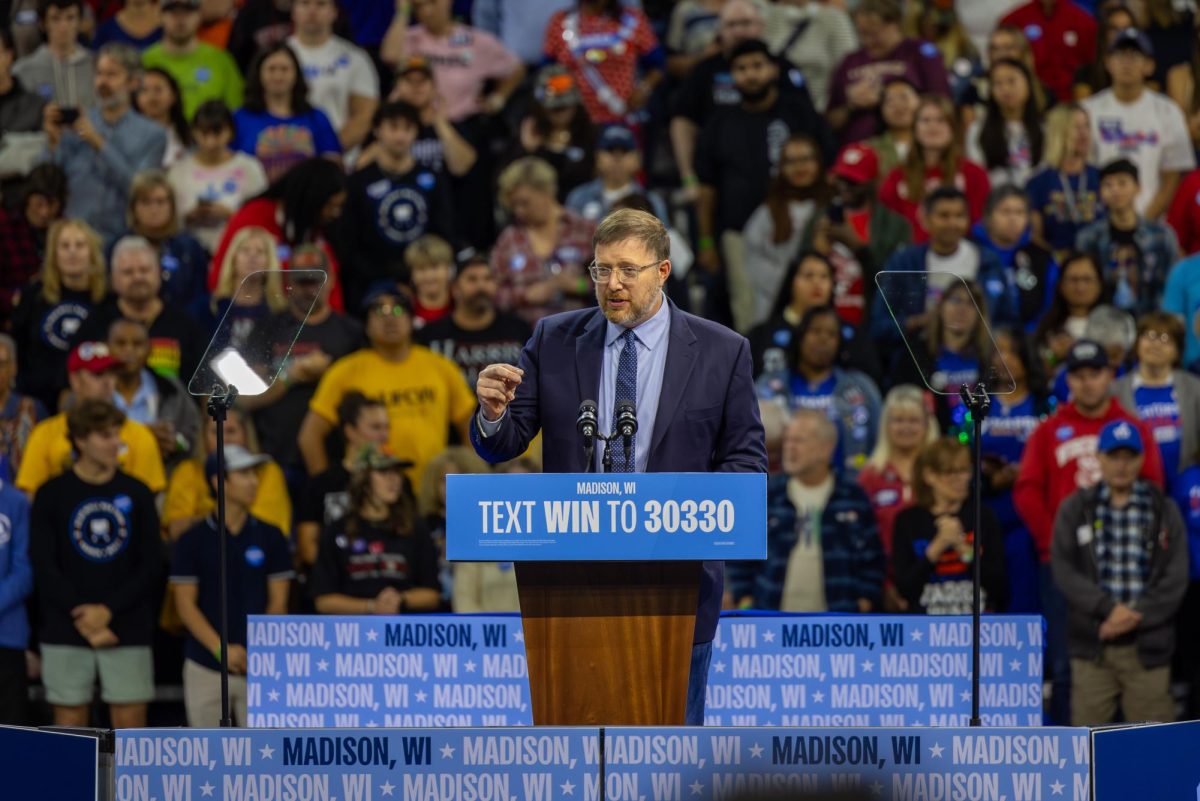

Steve Noyce, a University of Wisconsin civil and environmental engineering professor with a specialty in transportation engineering, said teen drivers lack the appropriate experience needed to drive in poor or dangerous conditions.

“Think back to your driving test, essentially what they teach you is to keep the vehicle in the lines,” Noyce said. “We don’t teach young drivers to handle a vehicle in adverse conditions.”

Wisconsin has a graduated driver’s license program, meaning a new 16-year-old driver is limited in what they can do while driving, such as having multiple passengers or talking on cell phones, Noyce said.

According to data from the DOT, after the graduated driver’s license program was created in 2000, over the following three years the number of 16-year-old drivers involved in crashes decreased 15 percent, and those involved in a fatal crash decreased 18 percent.

Noyce said while he would prefer to change the driving age to 18 or even higher, the graduated driver’s license program is likely as far-reaching as driving restrictions for teens will go because of Wisconsin’s agriculturally-based economy.

“Like many midwestern states, the Wisconsin economy from day one has been built around agriculture,” he said. “Kids that were born on farms became laborers, and to make farm families operate, kids began operating farm equipment at a young age, including on-road vehicles.”

However, Noyce said research behind the maturity of teen brains related to decision-making and risk is fairly solid, and gives him reason to think the driving age should be higher than 16.

As an older driver, Noyce said it is easy for him and others to think teen drivers are simply kids when they take risks while driving, but research proves otherwise.

“You tend to write it off as kids being crazy but there is actually a cognitive biology component that says it’s not the stupid kid syndrome, but there is actually a whole mental maturity element that is taking place,” he said. “A young driver hasn’t matured enough to understand the risks taking place.”

Despite many crashes from teen driving resulting from high speed, Noyce said he still backs the bill to change the speed limit on rural highways from 65 to 70, which was recently passed by the state Assembly.

Pam Moen, a spokesperson for AAA Wisconsin, said in a previous interview with The Badger Herald, an “across the board” increase should not happen without addressing data surrounding traffic safety and speed.

Noyce said from his research, drivers don’t drive faster than what they are comfortable with, so increasing the speed limit to 70 would not affect safety as much as many think.

“If you survey friends or other people, most are not comfortable with going over the low 70s, so what they’ve seen in other states is that [the speed] has only gone up a couple miles per hour,” Noyce said.