A study released Tuesday by the Great Lakes Committee shows despite some long term progress, the mercury pollution in certain areas of the Great Lakes remains a large-scale problem that poses potential threats to human and environmental health.

According to the study, mercury levels have declined over the past four decades, but many concentrations in the inland lakes, rivers and wetlands remain at levels that could pose a risk to humans and aquatic ecology.

One of the most striking findings of the study was that of the 15 most common fish species consumed by people in states that border the Great Lakes, six of these species have average mercury concentrations above the risk threshold for fish-eating wildlife in certain inland waters of the region.

The study also said the number of documented wildlife species affected by mercury contamination has increased substantially. For example, over the past two decades, the number of bird species cited in the scientific literature as affected by mercury has increased by a factor of six.

According to the Biodiversity Research Institute’s website, the Great Lakes Commission, which is funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, sponsored the scientific study in 2008, which involved more than 170 scientists and managers working to compile and evaluate more than 300,000 mercury measurements and to conduct new modeling and analyses.

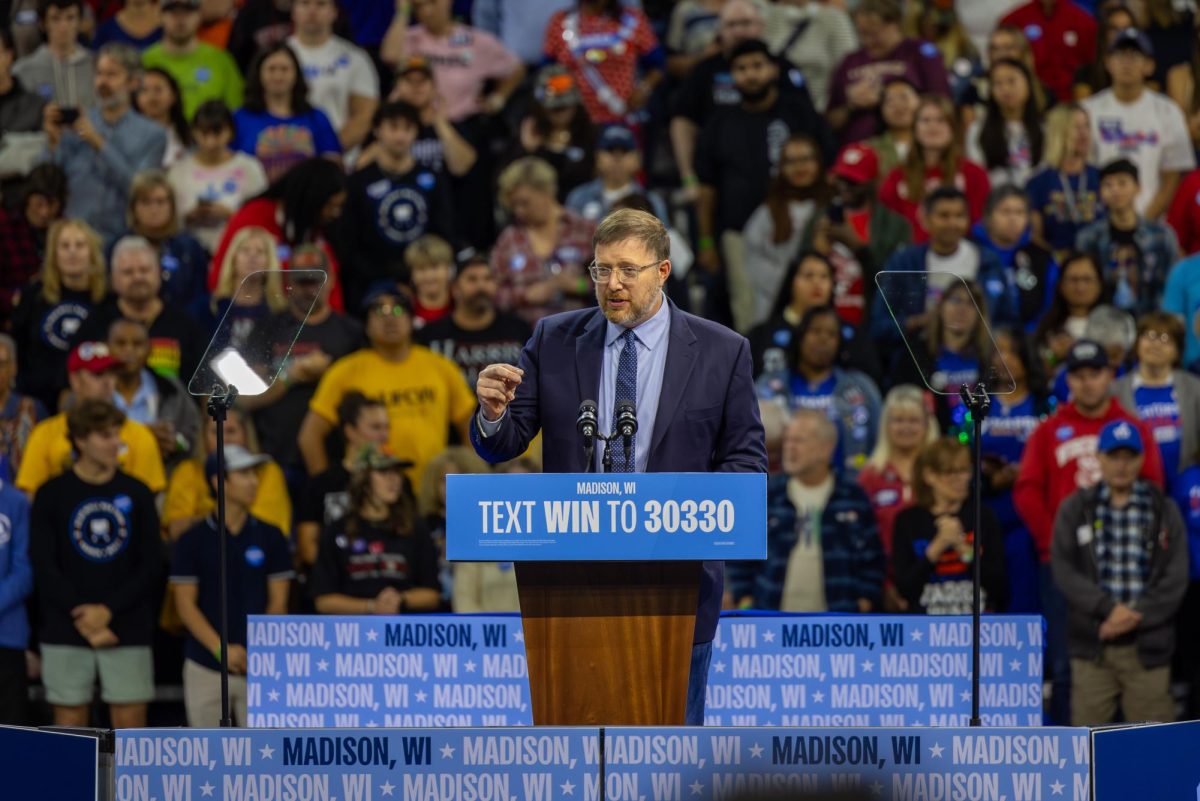

University of Wisconsin professor Peter McIntyre explained mercury coming out of the smoke stacks from coal fire power plants enters the atmosphere and eventually finds its way into the food webs of certain surrounding wetlands and eventually the fish that live in them. If humans eat these tainted fish several times per week, they could be susceptible to mercury poisoning.

“There is a downward trend in mercury trends over time in the Great Lakes region,” McIntyre said. “However, in small lakes that have wetlands around them, like the northern Wisconsin or Minnesota lakes, they are actually increasing. That’s the mystery here.”

This study was released just days after the United States House of Representatives approved a bill to delay certain EPA regulations regarding new national emission standards for hazardous air pollutants.

The measure includes the mercury emissions coming from smoke stacks in power plants near the Great Lakes.

“There are technologies to diminish the pollutant’s effect, but they haven’t been implemented as quickly as they could be,” McIntyre said. “There has been a lot of debate about whether the costs of implementing control of mercury emissions are worth the benefit to reduce mercury loads in wildlife and the environment.”

According to EPA’s website, the bill would also likely delay the agency’s rule introduced in July that would cut smog and soot from coal-fired plants. That rule would add costs to power generators and would force coal-fired plants in 27 states to slash the amount of pollution they currently emit.

“Congress is trying to kill [the new EPA] regulations,” McIntyre said. “This is a major public health issue. [The people of Wisconsin] want to be able to eat fish from lakes. The fact that Congress is preventing what is quite sensible regulations is, from a public health perspective, a travesty.”