As part of the Wisconsin Union Directorate’s Distinguished Lecture Series, Chaz Wheelock, an Oneida Nation West member, spoke on the intersection of indigenous people’s rights and environmental justice.

To begin the lecture, the DLS Committee acknowledged that the University of Wisconsin was built on land stolen from the Ho-Chunk, one of 12 nations native to Wisconsin.

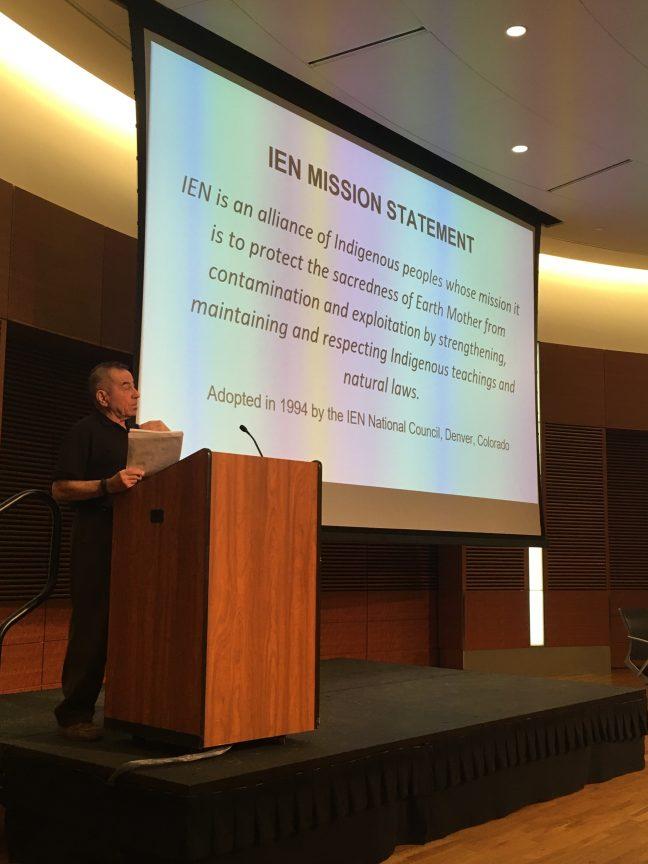

Wheelock has worked with the Oneida nation to advocate for education and land recovery efforts and as a tribal liaison for the Indigenous Environmental Network, an indigenous people’s alliance dedicated to protecting the environment in accordance to indigenous teachings. During the 1970s he helped establish the Iroquois Farms, a tribal organic agriculture venture whose cooperative management structure reflected the Oneida worldview on cooperation.

Wheelock talked about the importance of shared culture. He said that, moving forward, it’s important for native groups and federal governments to collaborate in order to protect the land and proceed sustainably. He emphasized futuristic thinking as a tool to help build sustainably.

Distinguished lecturer discusses Ho-Chunk land UW was built on

“I think one of the main takeaways is that we’re in a critical state,” Wheelock said. “We need to respond with more intelligence than we’ve ever had before.”

But Wheelock said a focus on economically feasible growth is also important, as long as it’s done sustainably, in order to support native communities and restore damage to sacred sites moving forward. He said native groups and government organizations should meet on a regular basis at levels ranging from local to national in order to work together and devise solutions favorable for everyone.

Wheelock said he’s worked with the Climate Justice Alliance to help fight the growing problem of climate change, which impacts both indigenous tribes and federal agencies. He highlighted Ecuador as the only country whose constitution guarantees water as a human right.

UW pays respect to Ho-Chunk history with indigenous people’s textiles exhibit

“One of the emphases we have as well is understanding the concept of discovery, colonialism, culture issues, assimilation,” Wheelock said. “All of their impacts.”

While environmental protection has always relied on contributions from the scientific community, Wheelock said current perspectives have evolved to incorporate indigenous knowledge as well.

“There’s a lot of emphasis on scientific knowledge, but now we have evolved in our thinking to know that indigenous knowledge has value as well,” Wheelock said.

Wheelock said the legacy of colonialism has continued to impact native communities, especially when it comes to the environment. He said it would be important to work towards democratizing wealth, so resources aren’t clustered in the hands of the historically wealthy, while native communities still suffer from the lingering effects of colonialism. He also mentioned redistributing the rights to production and consumption , rights natives have lost in the past.

UW orgs unite to bring ‘Tribal Histories’ documentary series to Union South

Wheelock said many industries built plants bordering on native lands, which impinged on their right to their own land by industrializing the land unsustainably. Wheelock said many of these plants focus on resource extraction specifically, which goes against native values of sustainability.

“I think that future thinking needs to be defined, refined and better understood,” Wheelock said. “It’s not just repeating the past, there’s a new transformation that’s returned.”

Wheelock also expressed frustration with the decades it has taken for indigenous rights to become acknowledged and recognized.

In 2007 the United Nations passed a non-binding resolution on the rights of indigenous people by an overwhelming majority. But Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States voted against the resolution, saying its language went too far when it came to the land ownership, veto power and the jurisdiction over resources it gave to people.

“I think one of the main takeaways is that we’re in a critical state,” Wheelock said. “We need to respond with more intelligence than we’ve ever had before. I think that future thinking needs to be defined, refined and better understood. It’s not just repeating the past, there’s a new transformation that’s returned.”