Emily Bazelon, a staff writer for The New York Times Magazine, presented on the mass incarceration problem in the U.S. and how prosecutors could be key in criminal justice reform as a part of the WUD Distinguished Lecture Series, Tuesday Night.

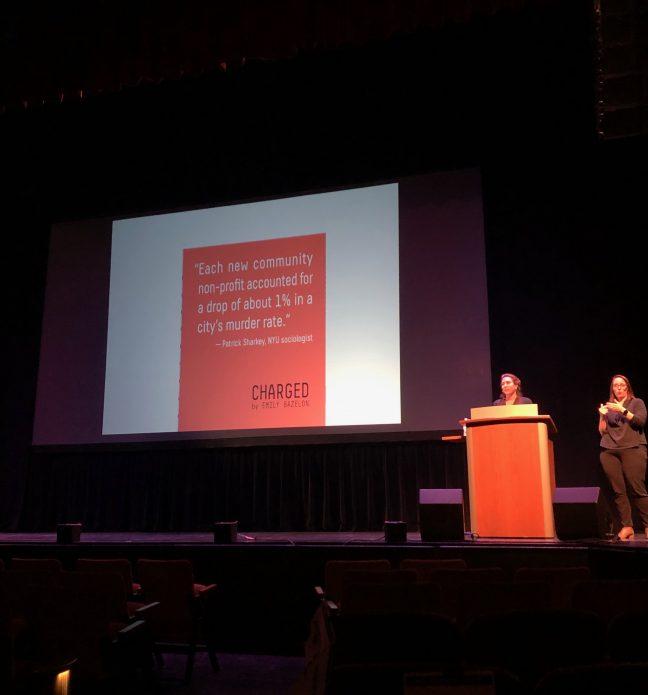

Bazelon specializes in reporting on legal issues in the U.S. and recently published a book “Charged,” detailing the complicated process and issues of the criminal justice system.

She first became interested in reporting on mass incarceration while reporting on California’s three-strike law. This experience sparked her interest in how mass incarceration relates to the power of prosecutors.

“I never realized that who your prosecutor is could shape the rest of your life,” Bazelon said. “Once I started noticing the disruption and the power that prosecutors have, I started to see it everywhere.”

While the prosecutor she interviewed for the story talked about reform for the three-strikes law, Bazelon saw an alternative option. She looked into how prosecutors’ discretion has influenced the influx of incarceration, and how their increased power in the criminal justice system is a more recent phenomenon with direct ties to mass incarceration.

Bazelon said when crime increased in the 1970’s and the public expressed concern, the legislatures responded by enacting mandatory minimum sentences. As a result, this shifted power from the judges to the prosecutors. This shift in power remains even as crime rates have dissipated.

Bazelon said this imbalance between crime and punishment is key in understanding the mass incarceration problem.

Redefining purpose, redirecting progress in the criminal justice system

“I think of this as a punishment machine,” Bazelon said. “We built [this system] for one set of problems that’s continuing to pump at this very high velocity.”

Bazelon also said plea bargains have become increasingly common, essentially making trials obsolete in the current justice system. She said the prosecutors’ job is to get convictions, making their level of power dangerous since they aren’t trained to be impartial like judges.

Bazelon said that today, the idea of a second chance boils down to the prosecutors’ discretion. Bazelon said the reverse effects of the current incarceration-focused system is manifested in the bail system, as the people who go to prison are more likely to commit another crime.

Bazelon said reform should take place in the amount of power given to prosecutors. The public can take the problem of mass incarceration into their hands by voting for progressive prosecutors.

Bazelon said this movement is urgent because, at the current rate of divergence between crime and punishment, it would take 75 years to cut the U.S. mass incarceration rate in half.

With the movement to elect a more descriptive and representative body of state prosecutors and influence the way the District Attorney runs, Bazelon said this incremental style of reform is a necessary step to tackling mass incarnation and how the American public views different types of crime.

“In order to really reimagine the criminal justice system, we have to reimagine how we think about second chances,” Bazelon said.